We must love one another or die.

This line appears near the end of W.H. Auden's poem "September First, 1939." Perhaps you've heard it by now; it was widely circulated in the wake of September Eleventh, 2001. It was alarmingly prescient: even though Auden was writing in response to Germany's march into Poland, his words would apply some 60 Septembers later.

We must love one another or die.

Auden did not say, "We will take no prisoners." He did not say, "Victory shall be swift." He did not even say, "The absence of evidence is not evidence of absence." Auden was not primarily concerned with nationalism or allegiance or well-drawn battle lines; he was concerned with taking artistic risks. And he did. There's an Auden for almost every occasion; there's even an Auden for this year's class of '03, a class that in my case began, and now ends, its time here talking about war. It's called "Musée des Beaux Arts," and it starts like this:

About suffering they were never wrong

The Old Masters: how well they understood

Its human position; how it takes place

While someone else is eating or opening a window or just walking dully along....

|

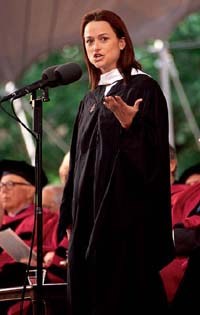

| Carpenter |

| Photograph by Jim Harrison |

Why is this our poem? Because, said another way, Auden saw that little things always occur with "big" things as their cinematic backdrops. Little things are things like theses, final papers, and wireless cards that fail. Little things are our answers to questions like "Who's dating whom?" "Who got which offer?" And, "Do blondes have more fun?" I saw my class find meaning in little thingsin revenue variance and balance sheets and how and why interest compounds. That meaning was the blessing we shared here at that time and in the months since. Academic life is rigorous. And in the rigor of its little things we found the best release of all.

Rigor. And love.

I remember introducing two friends in my sectionone Israeli, the other half-Pakistani, half-German. Their subsequent bond is just one star in an unending constellation that illustrates the trick of this extraordinary place: understanding the art of what's called "networking," but what, in its finer incarnations, is simply "Loving One Another." Loving one another happens naturally in this pressure-cooked paradise. We reach out here because we have to, because we can, and because there can be few places in the world where, when you're sad, you can lean on both a Navy SEAL and a Catholic priest.

Rigor. Love. And language.

A classmate of mine has been in hospital recovering from a car crash. He's here today, and he knows his poets, and I worry that he's frowning on my choice of Auden"too English, too predictable." He'd have had me quote Cortazar or Marivaux or Sophoclesbut he does know my point: Words Can Comfort Us. Words Can Change Us. And it is poets who best express the fact that knowledge is not confined by library walls, and disciplines are not split neatly by departmentsor by rivers. The heart of a poet can be coupled with the mind of a businessman. This is truth. This is veritas.

And this is why poetry's as pertinent to us as mastering spreadsheets, speaking fluent French, or deconstructing philosophical discourse. The precious thing about poems is that, like discounted cash flows, their "solutions" rest on our assumptions. The poem simply points out the possibility of interpretation; we as readers pursue those possibilities as we wish.

Rigor. Love. Language. And choice.

Not long after he'd written "September First, 1939," Auden decided thatin factit was "trash." On re-reading that astonishing lineWe must love one another or diehe said, "Well that's a damned lie! We must die anyway." And so, later anthologies omitted the work. But new critics took new looks, reassessed the poem's value, and chose to give it back. Why? Because it has meaning for us, and not even its author can take that away: We must love one another or die is what remains.