Football, a century ago, was an unruly, dangerous, and wildly exciting spectacle. It resembled rugby: minimal protective gear, no forward passes, mass plays that involved several players linking arms and thrusting forward, and a great deal of kickingboth of balls and opponents. The contests often turned into bloody brawls. Footballers poked at each other's eyes, threw haymakers, and leaped in the air like pro wrestlers to fall on a downed man with their full avoirdupois. In 1905, arguably the sport's most violent year ever, 18 players were killed on the field and 159 seriously injured, the fatalities coming mostly from brain concussions, spinal injuries, and body blows, according to John Sayle Watterson's College Football: History, Spectacle, Controversy. "I saw a Yale man throttleliterally throttleKernan, so that he dropped the ball," wrote an observer of the 1902 Harvard-Yale game, quoted in Football: The Ivy League Origins of an American Obsession, by Mark F. Bernstein. "The two hands reached up in plain view of every oneand all saw but the umpireand choked and choked; such a man would cheat at your cardtable."

|

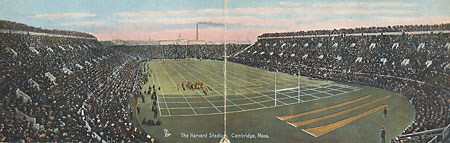

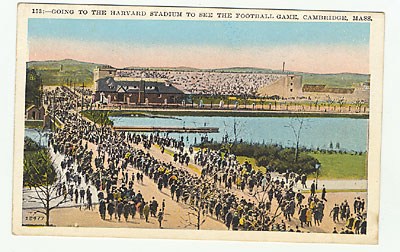

| This picture, from a postcard mailed in 1908, shows the Stadium when the field was truly a "gridiron." Note extra seating in wooden stands at the far end [view larger image]; steel stands had replaced them by the 1930s (below). Another postcard, sent in 1929, shows thronging crowds. |

| Postcards courtesy of Warren M. "Renny" Little |

The sport roused powerful passions and triggered primitive, atavistic celebrations. In 1911, after an 8-6 Princeton victory over Harvard, "A very tornado seemed to break loose on [Princeton's] Osborne Field," wrote a reporter quoted by Bernstein. "The crowd surged and swarmed down on the field for the snake dance. In columns ten or six abreast they pranced about the field, chanting incoherently, beside themselves with happiness, and over the bars of the goal posts they tossed their hats, felts, caps, and derbies in accordance with ancient custom."

|

The frenzy to win football games drove colleges to recruit ringersolder roughnecks who had merely a nodding acquaintance with academic lifeto play. Columbia's 1900 roster had only three undergraduates. Teams avidly sought out tough players and carefully schooled them in their prime mission: fomenting havoc on the gridiron. "The beef must be active, teachable, and intelligent," wrote Harvard coach William Reid, A.B. 1901, in his journal, quoted in Manhood at Harvard: William James and Others by Kim Townsend.

The games gushed cash. In 1893 the Yale Football Association's revenues of $31,000 surpassed the annual receipts of Yale's medical, art, or music departments, and by 1903 the gross was more than $100,000. The sport was so popular and lucrative that some felt football had begun to overshadow education as the mission of colleges. When he returned to Harvard to coach football in 1905, Reid collected a salary that was a third higher than any faculty member's and only slightly less than that paid the president of the University, according to Townsend.

Many called for drastic reformseven abolition of the game. Among those who spoke out, perhaps the most vociferous critic and surely the one with the highest profile was Harvard's Charles William Eliot, the first college president to roundly attack intercollegiate sports. Year after year, in his annual reports, Eliot lambasted football as a brutal and corrupting endeavor, antithetical to Harvard's educational mission. Given "the moral quality" of the game, he wrote in the 1903-04 report, as quoted by Watterson, "worse preparation for the real struggles and contests of life can hardly be imagined." Football, he believed, incapacitated students for intellectual activity.

Eliot denounced the competitive and deceptive aspects of athletics in general (criticizing baseball's curve ball, for example, because it deceived the batter). He abhorred the lawless mentality"an unwholesome desire for victory by whatever means"that overtook many athletes and coaches. Eliot felt it was wrong for college sports to entertain the general public, and that sports stole time away from the more rewarding pursuits of college life. To him, football did not so much build character as twist it in undesirable directions.

He was not alone, but by the end of the century, control of college football, particularly its financial aspects, had passed into the hands of the alumni. In the 1880s a Harvard athletic committee had tried to abolish football, and in 1895 the faculty voted two-to-one to do so, following a particularly violent game with Yale the previous fall. The athletic committee, dominated by alumni and students, voted unanimously to keep on playing, however, and the Harvard Corporation sided with the committee. In 1905 the faculty again tried to end football, this time with the Overseers' support, and that fall, even this magazine's progenitor, the Harvard Bulletin, recommended abolition, writing, as Bernstein notes, "Something is the matter with a game which grows more and more uninteresting every year."

|

| Scenes from a construction site, 1903. Above, laborers take a moment to pose. Below, three views of the Stadium as a work in progress. |

| Harvard University Archives |

|

| Courtesy of Turner Construction Company |

|

| Harvard University Archives |

|

| Harvard University Archives |

Yet amid this turmoil, something extraordinary happenedan event nearly inconceivable today. In 1903, despite President Eliot's fusillades, an enthusiastic band of Harvard alumni funded and had built a new arena for football games: the country's largest venue for intercollegiate sports.

Eliot harbored practical as well as philosophical concerns about the structure; he worried that it would become a white elephant once the football craze had blown over. Time has proven his fears groundless. This fall, Harvard Stadium, the first and oldest football field in America, observes its hundredth birthday with a special celebration on the weekend of the Princeton game, October 25. It is hard to overestimate the building's significance in football history. In the sport's formative years, the gridiron on Soldiers Field actually changed the way the game was played, and in some ways created football as we know it today.

Architecturally, the edifice remains magnificent. Only three football arenas in America hold the status of National Historic Landmarks: Harvard Stadium, Yale Bowl (opened 1914), and the Rose Bowl (1922). "It's a beautiful building," says Robert Campbell '58, M.Arch. '67, architectural writer for the Boston Globe. "It successfully employs classical imagery to suggest the tradition of athletics going back to Greece and Rome, but does so without pretension and without disguising the fact that this was probably the biggest single chunk of concrete in the world up to that time."

|

True enough. When built, Harvard Stadium was the largest reinforced concrete (i.e., concrete with embedded steel rods, also called ferroconcrete) building in the world, and the first massive structure ever made of that material. Some doubted that the new-fangled concrete could survive New England winters; the hardiness of a 6,300-foot concrete fence around Soldiers Field, erected several years before the Stadium, partly dispelled such fears. Others wondered if the new material might collapse under the weight of crowds. As a test, 12 men marched onto the seat slabs after they were set in place. "These men were...caused to jump up and down as nearly in unison as possible," reported the Harvard Engineering Journal for June 1904, in a special issue devoted to the Stadium. "The jumping was intended to bring to light what defects might appear from the boisterousness of the excited crowds soon to occupy them." The slabs' behavior "was entirely satisfactory." Even so, the construction manager perambulated beneath the Stadium's tiers during the first game played therewhether to preen, scout for problems, or to advertise his confidence in the structure is not known.

Ira Nelson Hollis, professor of mechanical engineering from 1883 to 1913, was central to the Stadium's creation. The chairman of the University athletic committee, Hollis was keen to build a permanent football facility. The wooden stands then in use were costly to maintain and posed a fire hazard; in fact, wooden bleachers on Soldiers Field caught fire during a spring 1903 baseball game with Princeton. Although no one was hurt, the bleachers were destroyed.

There was a treasure chest: the University had saved $75,000 from athletic receipts, and the fall of 1903 would bring in $25,000 more. Then, some alumni in their mid 40s made a larger project possible; two years before its twenty-fifth reunion, the class of 1879 had decided to up the ante from the reunion gifts of earlier classes, typically about $10,000. They kicked in $100,000, which went a long way toward the Stadium's eventual cost of $310,000. Recouping some of the outlay via ticket sales posed little problem; in 1903, the box office sent $12,000 back to alumni and students whose orders for Yale tickets could not be filled.

By the time the Stadium opened that November, Harvard had been playing football, or something like it, for nearly three decades. In 1874, the Crimson played its first football game against McGill on Jarvis Field, north of the Yard, where Littauer Center now stands. Other contests went off at Holmes Field, now mostly covered by the Law School's Langdell Library. In 1890, Major Henry Lee Higginson, A.B. 1855, changed the future of Harvard athletics by giving the University the 31 acres dedicated as Soldiers Field. His gift honors six young Harvard men"friends, comrades, kinsmen"who perished in the Civil War. Their names are engraved on a marble shaft that stands in the corner of Soldiers Field nearest Harvard Square (see "To the Victor ?").

Professor Frederick Law Olmsted, A.B. 1894, son of America's most famous landscape architect and a skilled landscape designer in his own right, took charge of siting the Stadium, and whether by luck or wisdom found an ideal location. "That turns out to be the only piece of land that could have supported so heavy a structure," says R. Victor Jones, Wallace professor of applied physics. "Until the dam went in [in 1911], the Charles River was very much a tidal stream and most of the land nearby was swampy and gummy. Other structures of this sort disappeared into the ground." But borings at the Stadium site disclosed hard gravel and clay to a depth of at least 40 feet.

The architectural plan modeled itself on ancient Greek stadia Harvard Stadium's length of 576 feet matches that of the great stadium in Athensand the design also recalls a small Roman circus. The architect was Charles Follen McKim of the New York firm McKim, Mead, and White (an honorary master's degree recipient in 1890), who took off from a design sketched several years earlier by assistant professor of civil engineering Lewis J. Johnson, A.B. 1887, along lines laid out by the Athletic Association. Much of the work was done by McKim's associate George B. de Gersdorff, A.B. 1888. Under Professor Hollis's supervision, officers, advanced students, and recent graduates of the Harvard Division of Engineering tackled the engineering tasks. The design called for 37 sections, with 31 rows per section, and a seating capacity of 22,000. In 1909 and 1910 the colonnade was added; that, plus wooden track seats on the field, brought the seating to nearly 40,000. (In 1929 additional steel stands enclosed the open end, boosting capacity again, to 57,750; these were dismantled in 1952 and today the Stadium seats 30,898.) Regarding other possible uses for the space beneath the seats, the 1904 Harvard Engineering Journal mentions handball courts and speculates that "The first addition will probably be a rifle range, as 130 yards can be found entirely free from obstruction and located in such a way that by no possible chance could a passer-by be injured."

|

The groundbreaking on June 22, 1903, kicked off an amazing frenzy of heavy work: the Stadium rose into the air in only four and a half months. That summer and fall, tireless construction crews poured 200,000 cubic feet of Portland cement. (Another 50,000 cubic feet were added the following spring.) All but one end of the east stand was finished when Harvard opposed Dartmouth on November 14, 1903, for the first game played there. More than 200 Italian workmen who had built the Stadium were in attendance, as was Franklin D. Roosevelt, A.B. 1904, who proposed to his date, his cousin Eleanor, the following day. The new field brought no luck to the Crimson, however; Harvard failed to score there that fall, losing to Dartmouth, 11-0, and a week later to Yale, 16-0. (Harvard later returned the favor, shellacking the Bulldogs, 36-0, when the new Yale Bowl first hosted The Game in 1914.)

The field itself is 481 feet long by 230 feet wide, a width just adequate for a football field and the running track that originally ran around its perimeter. Those dimensions played a crucial role in the evolution of football. In 1905, the outcry over the violence, foul play, and other abuses reached the highest office of the land: President Theodore Roosevelt, A.B. 1880, convened representatives from Harvard, Yale, and Princeton at the White House. Coach William Reid of Harvard was there, as was the overlord of college football, Yale's "advisory coach" and patriarch Walter Camp. The meeting ended with little more than promises, however, and that fall the gridiron mayhem went on unabated. In December, Columbia president Nicholas Murray Butler announced that his college was abolishing football, and MIT, Northwestern, Trinity, Duke, and others followed suit. Stanford and California switched to rugby.

With the sport in crisis, two rival rules committeesthe Intercollegiate Rules Committee (IRC) and the newly founded Intercollegiate Athletic Association (ICAA, which four years later changed its name to the National Collegiate Athletic Association, or NCAA)met in neighboring New York hotels in January 1906. Reid, with Roosevelt's backing, proposed 19 new rules to open up play and reduce the carnage. The proposals shortened the game from 70 to 60 minutes, added a neutral zone between the scrimmage lines to stem the fisticuffs there, required six men on the scrimmage line (to undercut the use of mass plays), increased the distance for a first down to 10 yards, and spread out defenders by legalizing the forward pass.

|

| Essential atmospherics: pennants for sale (above); the Harvard Band and its bass drum (below); spectators near the Band section |

| Harvard University Sports Information |

|

| Harvard University Archives |

|

| Harvard University Archives |

President Eliot had jawboned the Harvard Overseers into killing football unless the new rules were approved. Reid, a skillful politician and negotiator, used this as leverage. Reid explained "the new facts of life to Camp and the others," writes Bernstein. "Either the new 'rules go through or there will be no football at Harvard,' Reid told them; 'and if Harvard throws out the game, many other colleges will follow Harvard's lead, and an important blow will be dealt to the game.'"

Walter Camp was outmaneuvered, but continued to drag his feet. He was from the old school; he loved the running game and despised the forward pass, whose advocates had slipped past his defense and were making their way downfield. Camp suggested, as an alternative to the pass, opening up the game by making the field 40 feet wider, an idea that garnered some support. But the looming bulk of Harvard Stadium silently vetoed Camp's proposal: his widened playing field would not fit the Stadium's confines. The forward pass was saved, and paths of glory opened up for the likes of Y.A. Tittle, Johnny Unitas, and Jerry Rice.

After considerable wrangling, a joint committee of the IRC and ICAA adopted several reforms based on the Harvard proposals. In May 1906, the Harvard Corporation voted to play football for at least another season; the Overseers concurred. President Eliot voted with the minority on both occasions.

|

| The Game remains The Game: Harvard versus Yale, 2002 [view larger image] |

| Photograph by Stu Rosner |

History has now outvoted him as well, though the concerns he raisedviolence, professionalism, the worship of winning, and the overemphasis on sportsstill roil intercollegiate sports. Sphinx-like, the Stadium itself remains silent on the problems of football. Yet it is the only place on earth that has hosted a hundred years of the complex, hard-hitting game, and to the legions who have run, tackled, kicked, cheered, wept, and thrilled with excitement there, the verdict is most conclusively in.

John T. Bethell '54, who has long followed and written about Harvard football, served as editor of this magazine from 1966 to 1994.

|