Harvard Medical School, in an historic expansion rivaling the construction of its original white marble quadrangle a century ago, dedicated its new research building in late September. The glass-walled structureat 525,000 square feet, Harvard's largest research and education building everwill bring transparency to the parallel efforts of the clinical biomedical researchers within Harvard's affiliated teaching hospitals and the medical school's departments of genetics and pathology, uniting them in a single space. Speaking at the dedication, HMS genetics-department head Philip Leder '56 acknowledged that "it is a beautiful, indeed, even striking building [that] could easily stand as a work of art....But of course we realize that it is far more than that: it is, in fact, a colossal scientific instrument, larger than any other used in biology, created to shape the working lives of its occupants...."

|

| The New Research Building as seen from Avenue Louis Pasteur, looking south to the original Medical School quadrangle. |

| Photograph by Stu Rosner |

Designed and built in stages over a remarkably brief three-year span, the building is a monument to the pragmatic blend of form and function. Along the street, its three- and four-story-high façade, much of it glass, allows natural light to reach the windows of the preexisting Harvard Institutes of Medicine, which the new building now enfolds. The central entrance area includes a second-story café for the building's 800 occupants and their visitors, with a terrace above a waterfall. To the north of the east-west central corridor rises the 10-story research building, packed with the tools of biomedical science: laboratories, autoclaves, freezers, computing centers, and tissue-culture facilities. In this area, architects ARC/Architectural Resources Cambridge Inc. have included split-level eating and meeting areas. These two-story, glassed-in "pods" or "sky-lobbies," situated to take advantage of views of downtown Boston, house the mailboxes, coffee makers, and other amenities that are expected to bring researchers from otherwise separate floors of laboratories togetherwhether for formal meetings or serendipitous interactions by the proverbial water-cooler. At the corners of the building, to serve the same purpose, are what ARC principal architect Arthur Cohn calls "beacons." These triangular, prow-like glass featureswhich house lounges and meeting spacesjut out from the smooth plane of the façade.

To the south of the building's main corridor are its primary amenities: the café, a Zen rock garden (in the most heavily shaded part of the interior), a fitness facility, and the dramatic cone of the three-story conference center, clad in stainless steel panels and ringed with three balcony walkways, one at each level, all visible to passersby on Avenue Louis Pasteur. Inside, a first-floor auditorium seats 500 people. Breakout rooms line an adjacent, second-story, glass-walled corridor. On the third floor, a large oval room (divisible into two horseshoe-shaped spaces) will host seminars or banquets.

The $260-million building went up rapidly; despite a challenging, fast-track schedule of design and construction, it nevertheless came in "on time and under budget," says HMS director of engineering and construction Kevin Hurton. At the ribbon-cutting ceremony that celebrated the building's completion, dean of the medical school Joseph B. Martin said the school and the teaching hospitals "will join forces here" to accomplish their mission of alleviating human suffering and disease.

|

| The steel-clad conference center is visible through the glass façade, while the 10-story research tower rises behind it. |

|

|

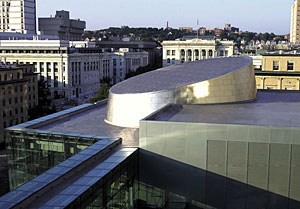

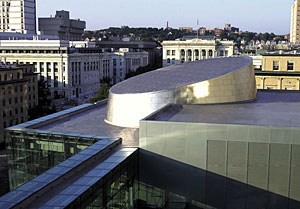

| The truncated top of the cone housing the conference center |

|

|

| The HMS genetics laboratory |

|

|

| A spiral staircase linking two floors of labs in a sky-lobby |

|

|

| The conference center exterior as seen from inside the building

|

|

|

| and its 500-seat auditorium. |

| Photographs by Stu Rosner |