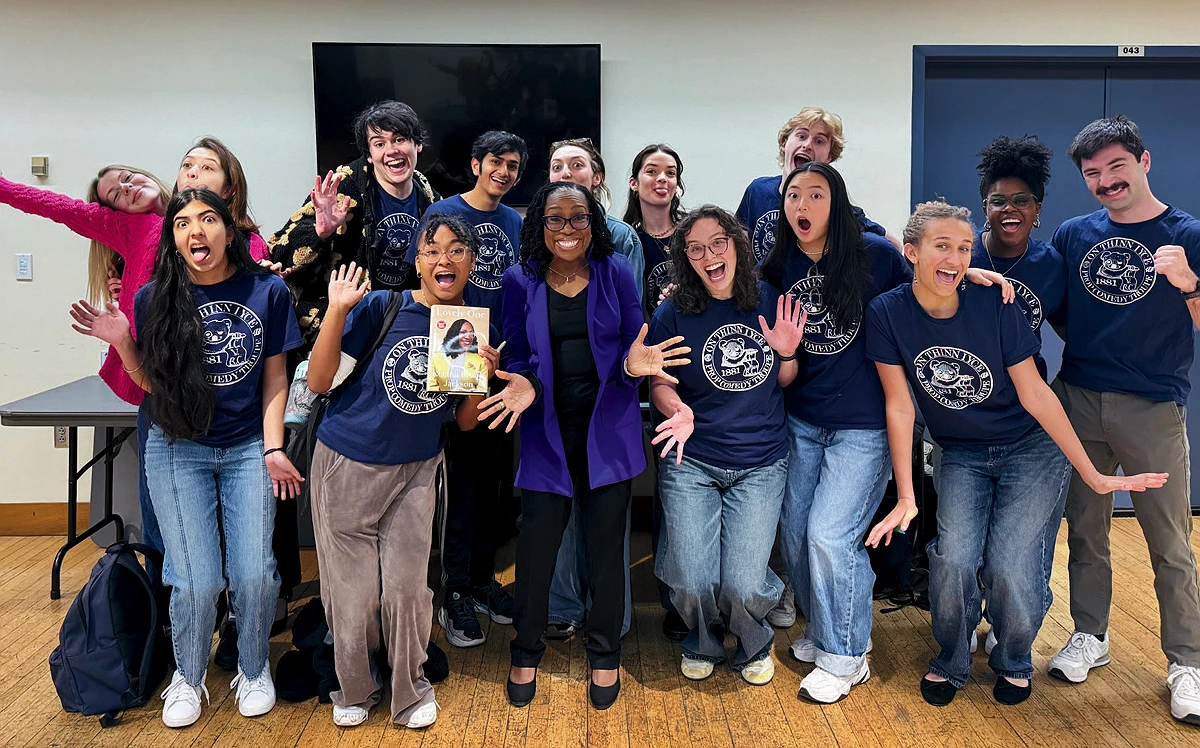

On a campus where student organizations vie for superlatives—from the nation’s “oldest continuously published student newspaper” to its “oldest collegiate social club”—the improvisational comedy troupe On Thin Ice claims a more idiosyncratic honor. It’s “the only improv group in the country with a Supreme Court justice as an alumna,” says co-president Aidan Kohn-Murphy ’26. “That’s our biggest flex.”

That would be Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson ’92, J.D. ’96, who performed with On Thin Ice—known on campus as OTI— during her undergraduate years. She was one of many students drawn over the years to Harvard’s constellation of improv, stand-up, and sketch comedy groups.

These clubs are younger and scrappier than their storied cousins—legacy institutions like the Lampoon and the Hasty Pudding Theatricals. Where those groups shroud themselves in secrecy and prestige, Harvard’s live comedy troupes favor openness and approachability. Most members arrive with no prior comedy experience; some have ambitions to pursue professional comedy, but many do not. During a time of political turmoil, the clubs offer a break from the headlines—and, sometimes, a way to reckon with them. And amid the pressures of campus life, they offer a chance to be absurd, present, and a little less self-conscious, at least for a few hours.

Jack Burton ’26 was one of the students who arrived at Harvard with little formal comedy experience—unless you count the time he pureed a fish in a blender at his fourth-grade talent show, channeling Dan Aykroyd’s 1976 “Bass-O-Matic” sketch from Saturday Night Live. In high school, as he participated in speech and debate competitions, Burton was particularly drawn to the humorous interpretation events; during those, winning felt less important than connecting with the audience. Once at Harvard, he discovered there were entire clubs built around that kind of performance.

On a whim, he auditioned for the Immediate Gratification Players, or IGP, another of Harvard’s improv troupes. There, he found a space free from the self-seriousness that can characterize many of Harvard’s social and extracurricular circles. The club’s irreverent spirit is reflected in its iconography: during shows, members wear signature red-and-yellow oversized ties—a jab at the formalwear of Harvard’s final clubs.

While there was no demanding comp process or schmoozy social events, auditioning for improv demanded a different kind of vulnerability, Burton says. He couldn’t hide behind secret bylines; he had no time to refine a scene or polish a punchline. “You get to see people processing on stage and developing characters,” he says, “and I think that’s really vulnerable.”

At IGP rehearsals, a group of around 15 students practice building scenes and worlds—without a script or advance planning. During his freshman year, as a new member, Burton had to learn patience, he says: to resist the impulse to rely on caricatures or exaggerated voices and instead develop scenes intentionally and collaboratively.

“One of the things we emphasize is that you don’t always have to be the funny man,” he says. “Being a better scene partner is more important than being the funniest person on stage.” Not that that lesson always sticks. During one recent campus performance, Burton recalls, a player said, “Let me speak!” His castmates turned that into a motif: for the rest of the show, nearly every scene ended as soon as he started talking.

Sometimes, the bit extends even longer. In 2000, at an improv festival at Skidmore College, half of IGP pretended to be from another school, then got into a fistfight onstage with the other half of the group. The club’s president never broke character—even when the police were called to break up the fight. IGP was banned from the Skidmore improv festival until 2024…when they staged a similar skirmish.

Like many performance comedy groups, IGP strives to be inclusive, says co-president Myra Bhathena ’26. Rehearsals are playful. Though the club has auditions, it hosts monthly open practices that anyone can join. Meanwhile, the Harvard College Stand-Up Comic Society (HCSUCS, pronounced the way you think) doesn’t hold auditions at all—it welcomes anyone with a joke to tell. Co-president Hamza Masoud ’26 grew up watching stand-up specials and late-night comedy, but his high school didn’t have any comedy groups. His first time trying stand-up was at a talent show during Harvard’s pre-orientation. “It was terrible,” he says. “I got, like, two laughs.”

But he decided to try again, taking the stage at another talent show a week later. “So, as you guys can tell, I’m going to be doing some stand-up comedy for you,” he began. “I know this is a talent show, but stand-up comedy isn’t really a talent. It’s something that unskilled, unmotivated, untalented people do to feel special.” A pause. “It’s kind of like majoring in economics.” The crowd laughed, and he knew he’d stick with it.

Stand-up, more than other formats, requires space to fail, says fellow co-president Jude Ha ’26. “I was not very funny for a long time,” she says. “I’m still not very funny frequently.” That’s why the club has no auditions, and why providing laughs is as important as providing feedback. “You’re exposing yourself to a lot of judgment, and very few people are good at stand-up the first few times they try it,” Ha says. “You need an environment where you can try, mess up, and learn from it.” Fortunately, the audiences in a Science Center lecture hall—or even in Sanders Theatre—are friendlier than those at a professional comedy club.

Comedy can also provide a way to process politically fraught moments, says Kohn-Murphy, the co-president of On Thin Ice. It’s a dynamic he’s familiar with: during Justice Jackson’s confirmation hearings in 2022, his high school—Georgetown Day School in Washington, D.C., where Jackson had served on the board—became the center of a political controversy. “Senators were digging through our library trying to prove we were some kind of woke, crazy leftist school—which, like, I wish,” he says.

But the headlines provided material for his high school’s improv group, where students impersonated senators ranting about books from their library. (“A lot of my improv has bizarrely been related to Ketanji Brown Jackson,” Kohn-Murphy explains.) Today at Harvard, students channel a similar impulse. “I don’t have a set tonight, but I have concepts of a set,” Masoud would say to open shows after the September 2024 presidential debate, when then-candidate Donald Trump said he had “concepts of a plan” to replace the Affordable Care Act.

That irreverent approach to politics also shaped Kohn-Murphy’s organizing. In high school, he co-founded Gen Z for Change, a nonprofit that uses social media to mobilize young people around progressive causes. When a Texas pro-life group launched an abortion whistleblower website, encouraging people to report anyone they suspected of undergoing the procedure, Gen Z for Change created a code that allowed individuals to flood the system with false submissions. “People sent in the script of the Bee Movie,” he says. “People sent, like, pornographic drawings of Shrek.”

“To do improv, you have to be a little bit weird....Not to say we’re all on SSRIs, but most of us are.”

In high school, improv also served a more personal purpose. “My parents had just gotten divorced. I was deep in the closet. I didn’t really know who I was,” Kohn-Murphy says. “But I knew I loved comedy, and I knew people thought I was funny.” Joining his school’s improv troupe gave him a place to explore ways of being that didn’t require certainty. “It shaped the trajectory of the rest of high school, and the community that I found,” he says.

That’s why he now helps lead On Thin Ice at Harvard: to provide that kind of space to other students. “To do improv, you have to be a little bit weird—like, your brain. Not to say we’re all on SSRIs, but most of us are,” he says. “You’ve just got to be a little offbeat. And creating spaces where people can find their people—that’s been so important for me. And I’d like to think it’s been helpful for others, too.”