Photographs by David Arnold and H. Bradford Washburn

The breathtaking aerial photographs of mountains and glaciers shot by H. Bradford Washburn Jr. ’33, A.M. ’60, L.H.D. ’75, during a lifetime of exploratory cartography captured a frozen wilderness that none but the most adventurous explorers could ever hope to see. This magazine published a portfolio of his work, “Sixty Years on High,” in 1993. Here, Washburn’s dramatic vistas take on a new role, documenting the effects of climate change. The dazzling rivers of ice and snow-topped mountains he photographed from the 1930s through the 1960s are melting.

Last summer, photographer David Arnold ’71 set out to shoot a few of these places from the same angles, positions, and altitudes used by Washburn. He hired bush planes and a helicopter and waited out weeks of bad weather to create this remarkable before-and-after series, a visual record of the changes wrought by rising global temperatures. Glacier Bay National Park will have no glaciers by 2030, experts predict, and the North Pole in summer will soon be nothing but a vast expanse of ocean. Worldwide, the melting has already increased the earth’s tendency to absorb the sun’s heat, which snow and ice would have reflected back into space. In the grand scheme of things, the water melting from mountain glaciers such as these will raise global sea levels only a little. But the changes seen here are portents of what will come. The continental ice sheets in Greenland and western Antarctica contain enough water to raise the oceans by more than 40 feet. Today, they are sliding and melting into the ocean faster than scientists thought possible just one year ago. Washburn couldn’t have realized he was photographing frozen landscapes that no one, not even the most intrepid adventurer, will ever see again.

~J.S.S.

Photographs ©David Arnold and ©Bradford Washburn / Courtesy Panopticon Gallery, Waltham, Massachusetts

(Above) In August 1938, when Bradford Washburn photographed the Nunatak Glacier in Alaska, it was actively calving icebergs. By June 2005, when David Arnold shot the same scene, the glacier had retreated far from the sea (below); more snow appears on the mountaintops in 2005 because the image was made considerably earlier in the summer.

(Above) The annual bands created as this glacier flows in and then out of an hourglass of rock caught Washburn’s eye in 1938. In 2002, he wrote Alaskan officials, pleading that they name the glacier, though he’d not seen it in 64 years: “It’s a very important little geological feature.” Now thinned and broken (below), it may be gone before it gets a name.

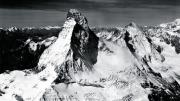

(Above) The Matterhorn, icon of the Alps, straddles the Swiss-Italian border. Washburn’s photograph, taken in August 1960, shows a thick mantle of snow and ice, largely melted by 2005 (below). In 2003, permafrost on the upper slopes melted for the first time, releasing a series of massive rock slides, says Arnold: 70 climbers had to be evacuated by helicopter, one of the biggest mass rescues in mountaineering history.

(Above) The Hugh Miller Glacier in Glacier Bay National Park as seen in 1940 was no longer visible at the time of Arnold’s 2005 visit —only a mud flat remained. Temperatures in this area have risen almost five degrees Fahrenheit, coaxing trees to spring up and thrive.