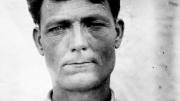

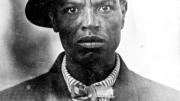

The faces haunt one--eyes gazing back at the lens with a resignation so profound as to have passed beyond caring. These are unusual photographic portraits in which “the sitter has no interest in the photo, and the photographer has no interest in the photo,” says Bruce Jackson. “Yet these pictures show someone in a very vulnerable situation.” That situation is one of incarceration at Cummins Prison Farm in Arkansas; the portraits are ID photos taken of (and by) inmates between 1915 and 1940. Sixty-two of the pictures are of prisoners from the Cummins women’s unit. With digital technology, Jackson has restored the images and published 121 of them in a new book, Pictures from a Drawer: Prison and the Art of Portraiture (Temple University Press).

A well-known photographer, documentary filmmaker, and ethnographer, Jackson was a junior fellow at Harvard from 1963 to 1967, and is now SUNY Distinguished Professor and Capen professor of American culture at the University at Buffalo, State University of New York. One thing that makes these prison portraits striking, he explains, is that they violate certain conventions of “how we take photos and how we allow photos of ourselves to be taken. Most of us have a ‘photo face’--women will show their teeth, men will stand up straighter. These pictures have a naturalness to them that is very difficult to acquire.”

Jackson acquired the pictures themselves quite easily. In 1962, he began an extensive body of work on prison as a cultural site, done primarily in Texas and Arkansas, that continued until 1979 and yielded several books, numerous articles, two documentary films, plus phonograph albums and CDs. He researched African-American work songs in Texas prisons, where the commissioner allowed him full access. Later he got similar support in Arkansas, where the prison system had become so dysfunctional that a federal judge declared incarceration there unconstitutional, because it represented cruel and unusual punishment.

In 1975, Jackson was at the Cummins Prison Farm on the last of his eight visits when an inmate who took identification photos motioned him into the room where he worked. The prisoner opened a drawer containing hundreds of loose prisoner ID pictures. “Help yourself,” he said. Jackson did as he was told, stuffing photographs into his jacket pocket and, as he says, “stole” 178 small prints from decades past.

The photographs all had patinas that often obscured the image. “Yellow, and not the charming yellow old photos get,” Jackson reports. He had to wait three decades until sufficiently advanced digital technology (specifically, the CS2 and CS3 versions of Photoshop) allowed him to restore the images to viewable condition. “Now, I can say: here’s this particular color band--let’s take it down,” he explains. But he did not remove scratches, fold marks, and deteriorations in an attempt to make the pictures look new. “These photos themselves are objects in time,” he explains. “Sometimes they are stained or ripped. The book shows both the prisoner’s face and the life the piece of paper itself has had.”

It is safe to say that the inmate photographers had no ego investment in their images, but the photographic documents they produced nevertheless have a lasting power. “Perhaps they didn’t know how to put a filter on a lens, or change the aperture for a sunny or cloudy day,” Jackson says, “but they knew how to make a picture in that room.