When specialized satellites orbiting Earth detect a star exploding anywhere in the universe, Edo Berger gets an alert on his cell phone. At 3:55 a.m. on April 23, the assistant professor of astronomy learned of a gamma-ray burst (GRB) from a star almost as old as time itself. GRB 090423, which exploded more than 13 billion years ago, at a time when the universe was just 625 million years old, is the oldest object yet discovered. The find was significant, he says, because it proved that stars began forming very quickly after the big bang: “within a few hundred million years.” Further research using gamma-ray bursts may eventually pinpoint the moment when stars began to form.

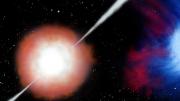

Cosmic explosions emit jets of gamma rays, a more energetic form of light even than x-rays (see the artist’s conception, above). But gamma rays don’t tell anything about the distance to an object, so when Berger first learned of the gamma-ray burst, he asked the Gemini Observatory in Hilo, Hawaii, to train its telescope on the dying star.

The fact that there was plenty of infrared light, but no visible light, coming from the explosion was “a smoking gun”: he knew at once that he had found an ancient star. That’s because the early universe was filled with hydrogen gas opaque to visible light. Later, as stars formed, their radiation ionized the hydrogen, creating clear pockets that transformed the universe into something that Berger says resembled Swiss cheese, before eventually reaching its present, essentially transparent state. Because all the visible light from the star’s explosion had been absorbed by hydrogen gas, Berger knew the light had begun its journey in the early universe; infrared observations confirmed that he was looking 95 percent of the way back to the beginning of time.

In the next five years, Berger hopes to pinpoint the period when the universe shifted from opaque to clear and also, by using more detailed observations, to learn something about when major chemical elements such as iron, oxygen, and magnesium first began to appear. “We know this process began even earlier,” he says, “because in this particular case, 625 million years after the big bang, we already see stars, and they are already dying.”