Falconry is the hunting of wild quarry using a trained bird of prey. Its practice and art may have begun in Mesopotamia four thousand years ago. Evidence suggests the sport was introduced into Japan by a Korean courtier in a.d. 359, to be enthusiastically developed by emperors, nobles, and members of the samurai class. Several families established their own schools of falconry around the fourteenth century, according to Kuniko McVey, librarian for the Japanese collection at Harvard-Yenching Library, and the teachings of the falconers were transmitted through notes for generations.

The library holds 11 Japanese books on falconry produced before 1800, all but one of them manuscripts, among its 1.3 million texts. Four of the works once belonged to Matsudaira Sadanobu (1759-1829), a chief senior councilor of the Tokugawa shogunate, and include the two pages reproduced here. They were copied then from manuscripts attributed to Jimyoin Motoharu, a celebrated calligrapher and a member of the Jimyoin falconry school, who made his copies in 1506. One manuscript is a copy of a text that had itself been copied in 1328, thus showing, says McVey, how this specialized knowledge was transmitted privately within a family of falconry experts for generations.

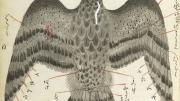

Falconers also use birds other than falcons. Jeremiah Trimble, curatorial associate in ornithology at the Museum of Comparative Zoology, guesses these two are meant to be Hodgson’s Hawk-eagles.

They were most recently sighted during “Take Note,” a two-day conference in November at the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study. The conference concluded a four-year initiative to explore the history and future of the book. The study of notes is intimately connected to the study of reading, a field newly poignant, as a report on the institute’s website points out, because “the rise of digital technology has made the encounter between book and reader seem more fragile and ghostly than ever.” Links to all the conference presentations may be found on this magazine’s website, and a link as well to an online exhibition of 73 note-related items from Harvard collections, ranging from these feathered friends to a second-century price list written on a potsherd, to a seventeenth-century German engraving of a “note-closet,” in which slips of paper could be hung on hooks corresponding to up to 3,000 alphabetized headings.