UPDATed DEcember 28, 2016: After multiple failed attempts to reproduce the results described below, Melton has retracted the original paper. However, He and his Colleagues Made a Significant Advance the following year That could lead to human therapies.

Xander University Professor Douglas Melton and postdoctoral fellow Peng Yi today announced that they have identified a hormone that induces reproduction of new insulin-producing beta cells in the pancreas, offering hope for a better way to treat type 2 diabetes. The disease, which is usually caused by lack of exercise and obesity, affects approximately 26 million Americans.

In type 2 diabetes, the pancreas doesn’t produce enough insulin to be able to manage a patient’s blood sugar; the patient also becomes increasingly resistant to insulin’s effects.

Melton—co-scientific director of the Harvard Stem Cell Institute—and Yi initially demonstrated the effectiveness of their new treatment in mice but have since found evidence that the same pathways on which the hormone works are active in humans. Melton hopes that betatrophin, the newly discovered hormone, will be approved for clinical testing in humans within five years. “If this could be used in people,” says Melton, co-chair of the University’s Department of Stem Cell and Regenerative Biology, “it could eventually mean that instead of taking insulin injections three times a day, you might take an injection of this hormone once a week or once a month, or in the best case maybe even once a year.”

The hormone works by causing beta cells to divide. Normally, only one in a thousand or one in ten thousand beta cells divides in a day. Betatrophin increased the rate of division 30 times in insulin-resistant mice. These mice began with only 10 percent to 15 percent of the normal complement of beta cells. In an experiment using betatrophin, Melton was able to triple those numbers in a week.

Melton has been seeking a cure for diabetes ever since his son, and later his daughter, were diagnosed with type 1 diabetes, a disease in which the immune system attacks and kills off insulin-producing beta cells. Melton said in an interview that this latest discovery is not likely to be an effective treatment for type 1 diabetes because it requires existing beta cells in a patient: the treatment works by causing those cells to divide.

But he says it might help in the early stages of type 1 diabetes, before all the beta cells had been eliminated. And it holds further promise: if in the future scientists find a way to stop the immune attack on beta cells, then betatrophin might become an important treatment for even the type 1 form of the disease.

Melton characterizes the discovery—published online April 25 in the journal Cell—as a lucky break, but says there were hints that he and Yi were on the track of something significant. “Before this work, it was known that the number of beta cells in humans goes up during pregnancy and when people become overweight or obese,” he says. “They need more beta cells and insulin to control blood sugar.” Melton and Yi found that this hormone also increases during pregnancy. “We looked in pregnant mice and found that when the animal becomes pregnant, this hormone is turned on to make more beta cells."

With federal funding for basic research into beta-cell replication, Melton and Yi have been working on this project for four years. But both clearly remember the moment of discovery on February 10, 2011. “I was just sitting there at the microscope looking at all these replicating beta cells,” recalls Yi, scarcely able to believe it. He had never “seen this kind of dramatic replication.” He printed what he was seeing and rushed into Melton’s office to show him.

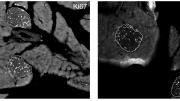

“I remember this very well,” Melton says. “It’s a black-and-white picture where you’re looking at a section, like a section through a sausage, of the whole pancreas. When you normally look at a black-and-white picture of that, it’s very hard to tell where the beta cells are, the insulin cells.

“But in this test, any cell that was dividing would shine up bright and white, like a sparkle," he continues. "He showed me this picture where the whole pancreas is largely black, but then there were these clusters, like stars of these white dots, which turned out to be all over the islets, the place where the beta cell sits. I still keep that black-and-white picture. We have much fancier color ones, but I like the black-and-white picture, because it’s one of those moments when you know something interesting has happened. This is not by accident. I’ve never seen any treatment that causes such an enormous leap…in beta-cell replication.”

In a press release, the University said that—working with Harvard’s Office of Technology Development—Melton and Yi already have a collaborative agreement with Evotec, a German biotech firm that now has 15 scientists working on betatrophin, and the compound has been licensed to Janssen Pharmaceuticals, a Johnson & Johnson company that also has scientists working to bring betatrophin into clinical use. The release went on to emphasize the importance of federal funding in facilitating the discovery.