The comments started small—a jab about her intelligence here, a comment on her body there. But this kind of sexual harassment soon became the defining feature of her graduate- school career, the young researcher explained to University of Illinois assistant professor of anthropology Kathryn Clancy ’01. It colored her relationships with colleagues and, ultimately, the professors who guarded the gates to the ivory tower. “Hazed’s” story, published on Clancy’s Scientific American blog, made ripples in the world of anthropology. And in the two years since the post appeared, one thing has become clear: among young female scientists, Hazed is far from alone.

In a new study published in PLOS ONE in July, Clancy and three fellow anthropologists—including Harvard assistant professor of human evolutionary biology Katie Hinde—have begun the process of exposing just how widespread sexual harassment and assault have become in scientific fieldwork. The study tracks the results of a 2013 online survey of more than 650 scientists and social scientists—half of them anthropologists and the rest representing more than 30 disciplines, including archaeology, biology, and zoology—for whom fieldwork is an essential part of the research process.

The authors found that 64 percent of those surveyed had personally experienced some sort of gender-based harassment while conducting fieldwork, including remarks about sex, physical appearance, or different intelligences between men and women. Twenty percent of respondents reported unwanted physical contact, including assault. “Here’s the reality,” Hinde says: “Every woman I know that does field research has a story of somebody they know, maybe not theirs, that had something bad happen to them in the field.”

The authors acknowledge several obvious caveats to the portrait these numbers paint, especially as surveys on such difficult topics come with trigger warnings and therefore track a self-selecting response pool. But, Hinde notes, the sensitive nature of sexual harassment and assault could cut both ways; some who’ve had negative experiences could be more likely to speak up, while others might avoid a survey that would force them to revisit their experiences. Hinde says that these percentages line up with what other research has found in work environments like business or the military. And regardless of sampling methods, she adds, “What our study shows was that there were hundreds of people reporting negative experiences, and dozens that were sexually assaulted. Quibbling about percentages is derailing the conversation about what matters.”

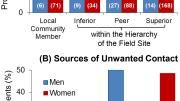

The study also found particularly revealing gendered differences in experiences of sexual harassment—with significant implications for how men and women can advance in the competitive and hierarchical world of academia. Female researchers were three and a half times more likely to have experienced sexual harassment, according to the survey. And, most significantly, the timing and sources of these incidents diverged for men and women, providing an important data point in the continuing debate over academia’s “leaky pipeline”—particularly in the still predominantly male STEM fields (science, technology, engineering, and mathematics). The researchers found that 90 percent of the women who’d reported sexual harassment were trainees at the time it occurred (70 percent of men were). And whereas men faced most harassment from peers, most unwanted advances toward female researchers came from their supervisors—the very professors who determine advancement along the tough path toward tenure.

“The psychological well-being impact—when it’s from up the hierarchy—is significantly higher. It can affect job performance, motivation,” especially at such important formative stages, says Hinde. Research output remains a significant metric for determining hiring and tenure review for young academics. A study presented last week at the American Sociological Association conference found that, in disciplines like sociology and computer science, women with the same research output as their male colleagues were still only about half as likely to gain tenure. And the results of the sexual-harassment study indicate that, in specialties where fieldwork is essential, women may face more obstacles to conducting similar levels of research. “In all the many discussions about ‘Why are women leaving STEM fields?’ ‘Why aren’t they making it into the professorate?’” Hinde explains, “nobody’s ever talking about this: they are being marginalized and pushed out because of egregious sexual behavior.”

To help change the culture of academic research, the authors of the PLOS ONE study emphasize that their findings are just the beginning of the conversation. Fieldwork sites, where workers from different institutions, and even countries, live and work in close proximity, can often feel far from the campus-based worlds of Title IX regulations and sexual-harassment policies. Less than a quarter of the survey’s respondents recalled working at a field site that explicitly discussed its sexual-harassment policies. But home-institution guidelines (Harvard announced its revamped, University-wide policy this summer) are expected to operate even in the field, and Hinde says that spreading awareness of the systems already in place will be a major part of reform. As she puts it, “It’s time for principal investigators to become principled investigators and institute cultural change.”