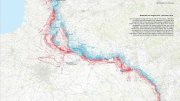

The centerpiece of an exhibition now at the Harvard Map Collection is a pieced-together map eight feet high by nine feet wide [the second image above] that shows at a glance the dimensions of the Western Front in World War I. German trenches are depicted in blue, Allied trenches in red, stretching for hundreds of miles. Winston Churchill later wrote of the scene at home: “We sit in calm, airy, silent rooms opening upon sunlit and embowered lawns, not a sound except of summer and of husbandry disturbs the peace; but seven million men, any ten thousand of whom could have annihilated the ancient armies, are in ceaseless battle from the Alps to the Ocean.”

Bonnie Burns, librarian for geographic information services, is the curator of From the Alps to the Ocean: Maps of the Western Front, at the collection in Pusey Library. During the war, she explains, “the massive changes that occurred in the field of military technology were mirrored in the field of mapmaking. New technologies, such as aerial photography, led to new cartographic techniques and to an increased reliance on maps. On the battlefield, cartographers were churning out maps of the trenches almost daily. At home, maps were being used to rally the home front in Europe and to try to convince the United States to join the Entente powers. Immediately after the war, maps were used to help decide how to redefine Europe.”

The collection has 350 individual maps of the front done by the French army mapmaking agency. Above are a map of the Argonne Forest showing the trenches, done on July 23, 1918, and a detail of those trenches from the large map. The scale of the large map is 1:300,000 (roughly 4.7 miles to the inch), but the original maps are at a scale of 1:20,000 and were updated as battlefield conditions altered, so that a student of the Western Front can track the waxing and waning of the slaughter. It ended, as this innovative exhibition will, on Armistice Day, November 11.