For the casual art lover, early American painting begins with John Singleton Copley’s portrait of Paul Revere. But as Theodore E. Stebbins Jr.—curator of American art emeritus at the Harvard Art Museums—points out, the colonies’ “rich visual culture” was more than a century old by the time Copley came on the scene.

A Copley graces the cover of American Paintings at Harvard: Volume One, a new book by Stebbins and former senior curatorial research associate Melissa Renn. Covering works of artists born before 1826, the volume also offers a complete record of Harvard’s holdings from this earlier visual culture: at least four of the 40-odd known surviving seventeenth-century American paintings, all portraits of early luminaries. (Harvard’s total might be as high as six or seven, but dating works from that era of rough recordkeeping is an imprecise art.)

The oldest American painting on campus is a portrait of Dr. John Clark. Its artist inscribed a date, 1664—though not, inconveniently, his name. On permanent loan from the Boston Medical Library, the painting hangs in the Medical School’s Countway Library. It shows Clark in much the same pose that Copley used for Paul Revere a century later: thoughtfully holding instruments of his trade. In his right hand is a trephine, a special tool designed to cut out pieces of skull.

Harvard owns outright several significant seventeenth-century works. They include an oval portrait of John Winthrop that art historians have dated to between 1660 and 1690, and a painting (above) by the colonies’ first artist who is known by name, Thomas Smith, dated from the same period.

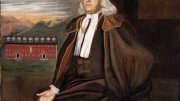

Stebbins’s favorite among this earliest group hangs in a corner of University Hall’s Faculty Room (which he calls “a chapel of eminent Harvard figures”). Modeling itself on Cambridge and Oxford, the colonial college quickly began soliciting the paintings of presidents, deans, and scholars that now line the room. Harvard added donors as well, and commissioned the portrait above of lieutenant governor William Stoughton, A.B. 1650, around the turn of the eighteenth century. His awkwardly rendered hand gestures toward the newly constructed Stoughton Hall and, somewhat bafflingly to those familiar with Cambridge topography, a misty mountain range beyond (perhaps a biblical allegory or a reference to Stoughton’s vast landholdings).

The early donor looks a bit stern, perhaps intentionally. “He was a widely disliked guy…a harsh and unrelenting Puritan” and the only judge from the Salem witch trials who never apologized, Stebbins says. Three-and-a-half centuries later, most students and faculty overlook the portraits that hang, as at Oxbridge, in dining halls, libraries, and reception rooms. But “each one of these paintings was a contemporary painting, in its day,” Stebbins reminds. “They were all modern, freshly made, of people who were important at the time.”