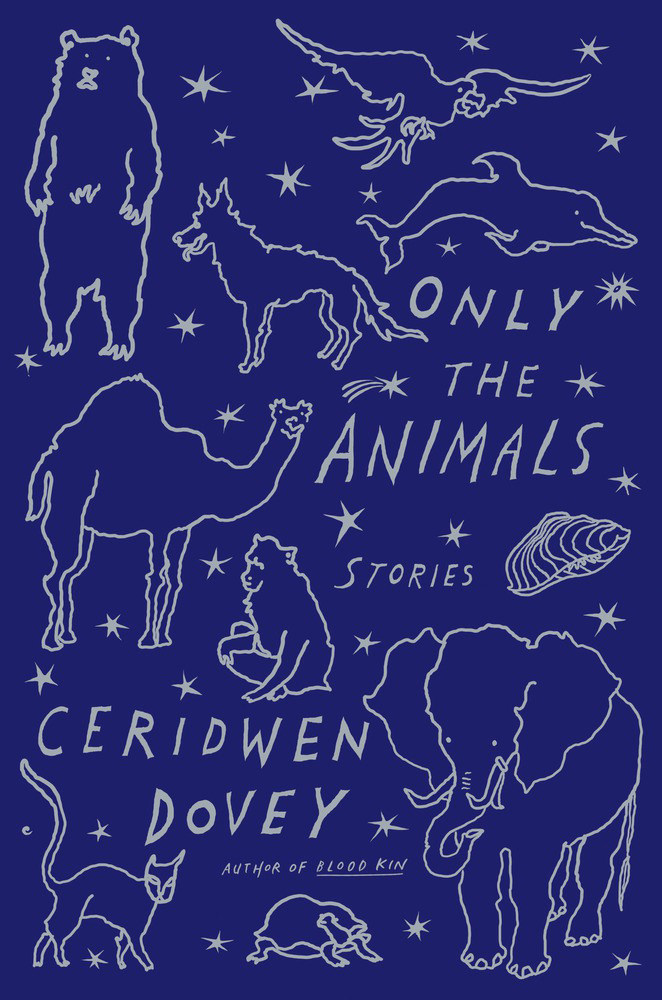

Only the Animals, by Ceridwen Dovey ’03, is a beautifully wrought, disconcerting collection of stories told by the souls of dead animals. A cat is picked off by a sniper on the Western Front; a blue mussel drowns in Pearl Harbor; a courageous tortoise is launched into Soviet-era space; and a self-mutilating parrot is abandoned in Beirut amid the 2006 Israeli air strikes. Yet Dovey lightens and layers these tales with humor, imagination, and an ingenious literary construct. Most of the animals are connected to writers—Colette, Jack Kerouac, and Gustave Flaubert, among others—who have featured animals in their own fiction, and can emulate their literary voices. (The Kerouacian mussel saying good-bye to a friend: “We didn’t understand but we let him go, hurting, as the flames of a hot red morning played upon the masts of fishing smacks and danced in the blue wavelets beneath the barnacled docks.”) Thus, what Dovey says began as “an experiment” in retelling historic incidents of mass suffering through voiceless, vulnerable beings “to shock readers into radical empathy” became, instead, “this weird mix of short story, literary biography, and essay—with lots of details that are true to life—and then also a sort of love-letter tribute to these authors who fascinate me.”

Published last year in Australia (Dovey lives in Sydney), Only the Animals elicited a helpful blurb from J.M. Coetzee, along with several awards; it was due out in the United Kingdom in August and Farrar, Straus and Giroux will release the American edition on September 15.

Some of the book’s themes—conflict, abuse of power, and the amorphous origins of cruelty, inspiration, and empathy—also surface in Dovey’s very different debut novel, Blood Kin (2007). Set in a nameless country during a military coup, the slim, edgy book mines the complexities of collusion, with an undercurrent of danger and eroticism, through the first-person accounts of the ex-president’s barber, cook, and portraitist, all of whom are imprisoned at a remote country estate.

No doubt Dovey draws from her childhood in apartheid-era South Africa. There was, she says, “a sense of being complicit [in the system] at some level because your privilege is conferred through the pain other people are experiencing. But you were too young to have been held fully accountable.” Her parents, Teresa Dovey, a pioneering scholar of Coetzee’s works, and Kenneth Dovey, an educational psychologist, were politically active. Political and personal reasons led the family to shuttle between South Africa and Australia five times between 1982 and 1987. By 1995 apartheid had ended, and the Doveys took sabbaticals in Sydney. When the time was up, however, Dovey and her sister—Lindiwe Dovey ’01, now an African film and culture scholar, teacher, and filmmaker in London—were so happy at school that they chose to stay on, alone. “It was a very brave decision for my parents to make,” she says. “They came and visited whenever they could. We were not abandoned at all.”

At Harvard, she concentrated in visual and environmental studies and anthropology, and for her senior thesis made a documentary film, Aftertaste, about changes in labor relations and cultures on South African “wine farms.” After graduation she moved to Cape Town, where she wrote Blood Kin, which was first published by Penguin South Africa. She returned to the United States for graduate studies in social anthropology at New York University, earned a master’s but left without a doctorate, then eloped in 2009 with her now-husband, Blake Munting, and moved back to Sydney, where their son, Gethin, was born in 2012. (They are expecting another child by the end of the year).

Writing has always been among Dovey’s “creative outlets.” She has actually completed eight novels (six of which, in her mind, don’t merit publication), but, despite positive reviews for Blood Kin, she continued to work as an environmental researcher and on ethnographic film projects until Only the Animals, which she readily calls “a strange book,” was published. “I never expected that. I was writing characters that were dead animals,” she explains, “and had no idea if I had gone completely nuts.” Rising confidence, along with a growing preference for the solitude and autonomy that literary art affords, led her to commit to writing full-time last year, including freelance nonfiction for The New Yorker’s blog.

Motherhood also played a role: “It made me more grateful for the time I have to write,” she adds—and ultimately more creative, especially while finishing Only the Animals in 2013. The nature of pregnancy, nursing, and caring for a newborn intensified her kinship with “the whole family of mammals.”

The book’s title stems from the work of Boria Sax: “What does it mean to be human? Perhaps only the animals can know.” Like Coetzee, Sax, an author and academic best known for his writings on animal-human relations, has influenced Dovey, who also admits to feeling “bewildered to the point of inaction in terms of the ethical responsibilities we have toward animals and the obligations we owe them as the dominant species on earth. We treat animals in the most appalling ways right now.”

Yet Only the Animals is apolitical. It engenders empathy, shame, and sadness, but also wonder at these spirited creatures. They face what life and death bring with enviable presence of mind and body, as visceral beings. “What choice did she have,” asks the parrot in Beirut, “but to hook my cage to the awning overhead and leave as quietly as she could, before I realized I was alone?”

“I am very aware that we are all creatures who suffer together, and that existence is hard for us all,” Dovey reflects. “There is something, also, about the bond we have with animals, the care and connection that we don’t appreciate or see the magic in as much as we should.” Animal guides, she points out, have graced children’s literature throughout the world. “They are like oracles, there at our very earliest attempts to build empathy and imagination.” And that takes work, she says: those capacities “do not come automatically, in the sense that cruelty is a failure of the imagination. Something happens in reading through these animal guides that is very tied up in what it means to be a good human being.”