The Harvard Museum of Natural History in November unveiled its new exhibition on marine life. The centerpiece (shown here), a cleverly lit diorama, depicts New England coastal waters from the shallows to the depths: a pioneering way to educate and entrance visitors without penning living specimens in a small habitat. That display neatly complements the adjacent gallery on the region’s forests, and closes what curators describe as a “gaping hole” in the exhibitions, which have underrepresented Earth’s aquatic environment and the staggering biodiversity it supports.

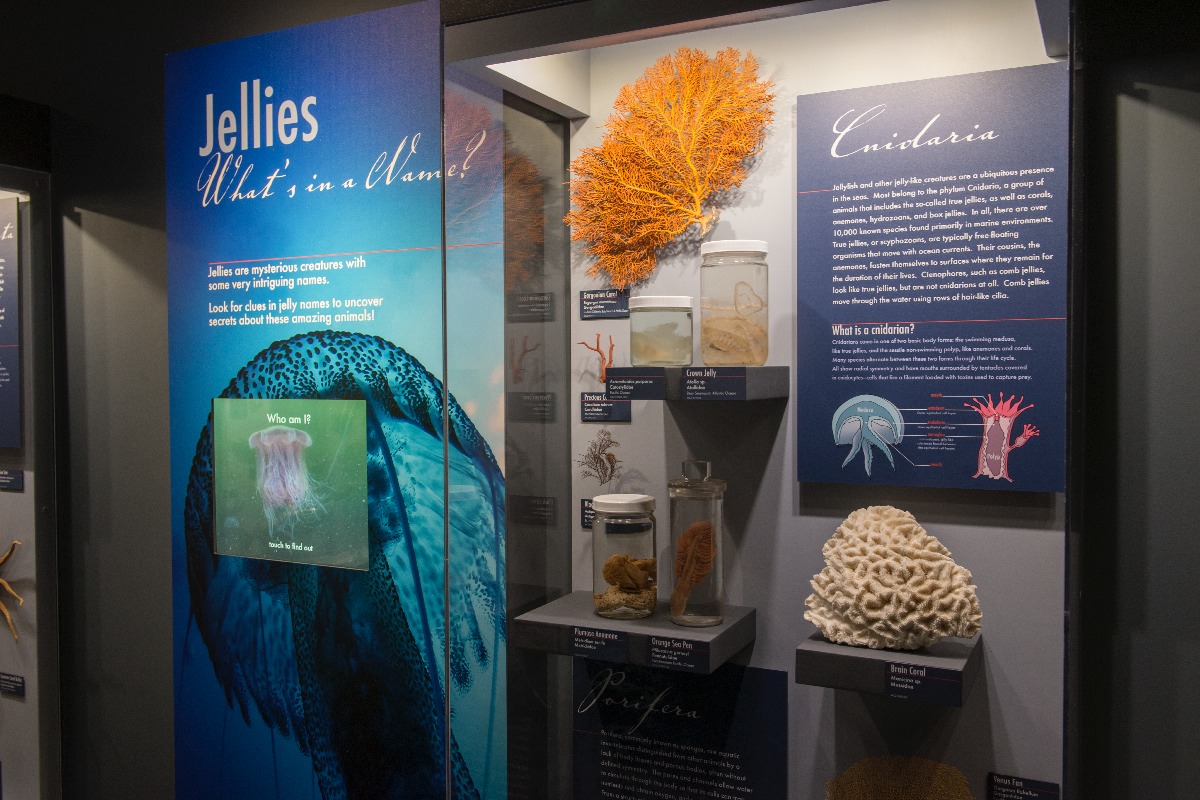

A few hundred mounted specimens in surrounding cases (from the millions of molluscs and fish among the comparative zoology holdings) give a sense of evolution, species variation, and the sheer beauty of nature. Youngsters will enjoy the interactive explanations of nomenclature (focusing on jellies), and of Harvard scientists’ work. They will likely like the huge Australian trumpet shell (Syrinx aruanus, a type of snail), and be thrilled or repelled by the giant isopod (Bathynomus giganteus, a crustacean) at rest in its jar. What parent could resist the vivid orange lion’s paw scallop (Nodipecten nodosus)—or withhold a smile at the name of the diminutive Wolf fangbelly (Petroscirtes lupus, one of the Pacific coral-reef combtooth blennies)?

In the diorama at the center of the new marine-life exhibition, the lighting design subtly transports viewers from the the sunlit surface of the water, at right, toward deeper habitats, on the left.

Photograph by Jim Harrison

In the diorama at the center of the new marine-life exhibition, the lighting design subtly transports viewers from the the sunlit surface of the water, at right, toward deeper habitats, on the left.

Photograph by Jim Harrison

On display in the cases surrounding the diorama are a few specimens from the millions held in the Museum of Comparative Zoology’s collection. This panel, on the Teleostei (ray-finned fishes), gives central pride of place to Jenkin’s Scorpionfish, a denizen of the eastern central Pacific, surrounded by various (distant) neighbors in that large ocean.

Photograph by Jim Harrison

The Australian trumpet (Syrinx aruanus), foreground, gives viewers a new sense of the sheer size a snail species can attain, and of the diversity of nature.

Photograph by Jim Harrison

The jellyfish and related species (corals, anemones, etc.) mostly belong to the phylum Cnidaria; in the exhibition, they play an important role in an interactive lesson about scientific naming.

Photograph by Jim Harrison

Crabs come in all sizes and body types, from the Puget Sound King (rightly named!) in the middle of this case to the familiar, but biologically dissimilar, Atlantic coastal horseshoe species.

Photograph by Jim Harrison

A vivid-orange lion’s paw scallop (Nodipecten nodosus)

Photograph by Jim Harrison

An Atlantic tarpon, a big fish with a big habitat: the western Atlantic, from Virginia to Brazil

Photograph by Jim Harrison

The skeletal displays include this hogfish.

Photograph by Jim Harrison

The intertidal habitat, shown here, imposes special burdens on its resident species, which must adapt to wave and temperature fluctuations, and even desiccation.

Photograph by Jim Harrison