Colson Whitehead ’91 has written a zombie-apocalypse novel, a coming-of-age novel set in the world of the black elite, a satiric allegory following a nomenclature consultant, a sprawling epic tracing the legend of the African American folk hero John Henry, a suite of lyrical essays in honor of New York City, and an account of drear and self-loathing in Las Vegas while losing $10,000 at the World Poker Series. That work has won him critical acclaim. He received a MacArthur Fellowship in 2002, and has been a finalist for almost every major literary award; he won the Dos Passos Prize in 2012 and a Guggenheim Fellowship in 2013. In an era when commercial pressure reinforces the writerly instinct to cultivate a recognizable “voice,” his astonishingly varied output, coupled with highly polished, virtuosic prose, makes Whitehead one of the most ambitious and unpredictable authors working today.

He has gained a reputation as a literary chameleon, deftly blurring the lines between literary and genre fiction, and using his uncanny abilities to inhabit and reinvent conventional frames in order to explore the themes of race, technology, history, and popular culture that continually resurface in his work. In a country where reading habits and reading publics are still more segregated than we often care to admit, his books enjoy a rare crossover appeal. His first novel, The Intuitionist, is a detective story that regularly turns up in college courses; the zombie thriller Zone One drew praise from literary critics and genre fiction fans alike; Sag Harbor, about black privileged kids coming of age in the 1980s, was a surprise bestseller.

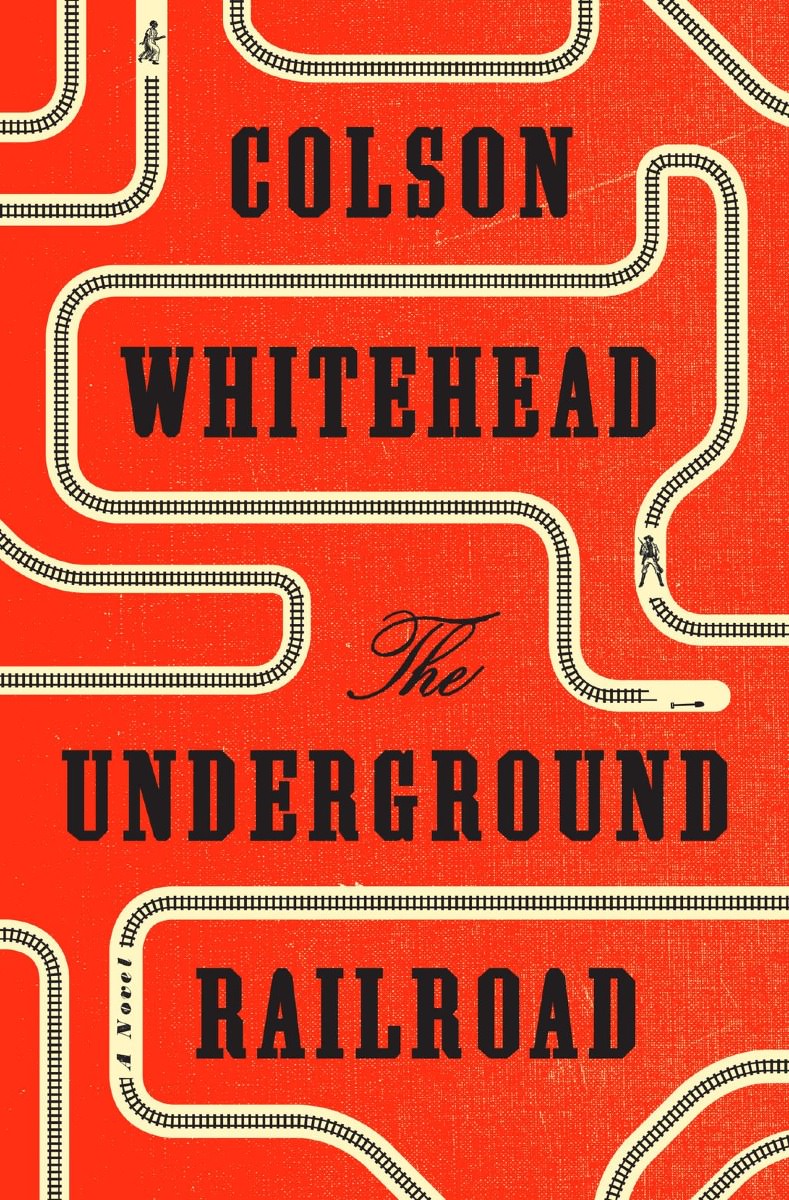

Whitehead’s new novel, The Underground Railroad, was released in August

Beyond the books, Whitehead swims effortlessly in the hyper-connected moment: he maintains an active presence on Twitter, where his sly and dyspeptic observations on the curious and the mundane have gained him a devoted following. A sampling includes sagacious tips for the aspiring writer—“Epigraphs are always better than what follows. Pick crappy epigraphs so you don’t look bad”—and riffs on Ezra Pound: “The apparition of these faces in the crowd / Petals on a wet, black bough / Probably hasn’t been gentrified though.” In the pages of The New York Times Magazine and The New Yorker, he has wryly dissected contemporary mores and the light-speed metamorphoses of language in the age of social media. In a widely shared essay from last year, he parsed the current attachment to the “tautophrase,” as in “you do you” and “it is what it is.” Or Taylor Swift’s popularization of “Haters gonna hate.” Swift makes an easy target, of course, but Whitehead takes aim at the rhetoric of those in power too, and the narcissism in our culture more generally. He’s more gadfly than moralist, but there is a Voltaire-like venom to his sarcasms. “The modern tautophrase empowers the individual,” he observes, “regardless of how shallow that individual is.”

At 46, Whitehead is approaching the mid-point of a successful writing career. He exudes the confidence and ease of a man settled in his craft, and for that reason is also inherently restless, driven to test his limits and keep himself vivid. In recent years, some observers have questioned whether he was taking up subjects rich and deserving enough of his abilities. Dwight Garner in his review of The Noble Hustle (the poker book), vividly praised Whitehead’s talent—“You could point him at anything—a carwash, a bake sale, the cleaning of snot from a toddler’s face—and I’d probably line up to read his account”—while making it very clear he felt it was being wasted. Garner called the book “a throwaway, a bluff, a large bet on a small hand,” and questioned the sincerity of the undertaking: “you can sense that he’s half embarrassed to be writing it.”

As if to answer that criticism, Whitehead’s new novel, The Underground Railroad, pursues perhaps the most formidable challenge of all: taking readers through “the blood-stained gate,” as Frederick Douglass called it, onto the historical ground of American slavery. The uncompromising result is at once dazzling and disorienting, the work of a writer flexing, firing on all cylinders.

During a recent conversation at an Italian café in the West Village, Whitehead at times seemed slightly distracted. It’s clear he does not enjoy talking about himself. He has always been highly skeptical of confessional modes. When he gives public talks, he likes to tell the audience he was born poor in the South—and then reveal he’s just quoting Steve Martin from The Jerk (in which Martin plays a white man who believes he is born to a family of black sharecroppers). “I never liked Holden Caufield, The Catcher in the Rye,” he declares with a wink in his eye, in a promotional video for his most autobiographical book, Sag Harbor. “I feel like if he’d just been given some Prozac or an Xbox, it would have been a much shorter book, and a much better book.”

In person, this stance becomes a kind of awkward warmth, even nerdiness: the eccentricity of the “blithely gifted,” to borrow John Updike’s 2001 assessment of “the young African-American writer to watch.” In dark blue jeans, his dreadlocks draping over a crisp white shirt, his glance slightly diffident behind neat glasses, Colson Whitehead is unmistakably a New Yorker—from Manhattan. He speaks in the native tongue—a streetwise blend of ironic nonchalance and snappy precision, a jolting rhythm not unlike that of the subway, always with an eye towards the next stop.

The Intuitionist registered as a shot across the bow, as though Whitehead were daring readers to box him in.

Whitehead was born in New York City and grew up mostly on the Upper West Side. He lives in Brooklyn now, but recalls Manhattan with affection. “I like how Broadway gets really wide up there, how close the Hudson is,” he says. “I’d live up there again if I could afford it.” Asked what it was like growing up, back in the day, he brushes off the perceived roughness of that era: “New York was pretty run-down in the ’70s and ’80s, but if you think that’s what a city looks like because you don’t know anything else, then it seems normal. When I got out of college, I lived in the East Village and on cracked-out blocks in Brooklyn, and that seemed pretty normal, too.”

He paints a picture of a loving and kind of average household. He was always surrounded by readers. “My mother reads a lot, and I had two older sisters, so their hand-me-down libraries were always around. I didn’t need to be pushed.” In a rare autobiographical essay, “A Psychotronic Childhood,” he has described how this period of his life was deeply saturated by television, comics, and the “slasher” and “splatter” flicks, then in vogue, that he watched in New York’s B-movie theaters. A self-described “shut-in,” he “preferred to lie on the living-room carpet, watching horror movies,” where one could acquire “an education on the subjects of sapphic vampires and ill-considered head transplants” while snacking “on Oscar Mayer baloney, which I rolled into cigarette-size payloads of processed meat.” Unsurprisingly, he read “a lot of commercial fiction, Stephen King—the first thick (to me) book I read was in fifth grade, King’s Night Shift. I read that over and over.” His early literary ambitions, he has said, were simple: “Put ‘the black’ in front of [the title of] every Stephen King novel, that’s what I wanted to do.”

After graduating from Trinity School, Whitehead entered Harvard. It was the late 1980s, and the way he tells it makes it sound like he was a poster boy for Gen X slackerdom. (The archetype must feel almost quaint to the hyper-networking Zuckerberg generation.) It’s not that he didn’t enjoy his time at Harvard—he did attend his twenty-fifth reunion, he informed me—but he seems to have been determined not to try too hard to be involved in anything, or to stand out in any way. He read in his room a lot, he says, absorbing a wide range of things. But it was the way he was absorbing these strains that is most revealing: “I think it helped that, for my first exposure to Beckett, I took it to be a form of high realism. A guy is buried up to his neck in sand and can’t move; he has an itch on his leg he can’t scratch. That sounds like Monday morning to me.” (Responding to the suggestion that his novels suggest the influence of Ralph Ellison and Thomas Pynchon, Whitehead is noncommittal but open to the idea: “What excited me about writers like Ellison and Pynchon was the way you could use fantasy and still get at social and political themes,” he says. “That was very revealing to me…like here’s this serious book on race, but it has all this wild stuff in it.”)

At Harvard, Whitehead played the role of young aspiring writer the way he imagined it. The results were not necessarily promising. “I considered myself a writer, but I didn’t actually write anything,” he says. “I wore black and smoked cigarettes, but I didn’t actually sit down and write, which apparently is part of the process of writing.” He applied to creative-writing seminars twice—and failed to get in both times.

The most important undergraduate legacy has been his lasting friendship with Kevin Young ’92, an aspiring, charismatic poet from Kansas who was already involved with The Dark Room Collective, a gathering of young black writers that has played a major role in shaping contemporary poetry during the past two decades. Whitehead, never more than peripherally involved, says, “Kevin was always more serious than I was. He already knew where he was going, what he was about….I wasn’t much of team player.”

After graduation, Whitehead gravitated back to New York City. He went to work at The Village Voice, writing album reviews and television criticism. He soon mastered the magazine’s signature downtown stir-fry of pop-culture fluency, melding high- and lowbrow, theory and snark, punk and hip-hop: an inevitable rite of passage, given his influences. “I came up in the seventies and eighties reading CREEM [“America’s Only Rock ’n’ Roll Magazine”], stuff like that, so I knew pretty early on that I wanted to be involved in that scene,” he says. Working in the book section at the Voice, he says, “was where I learned how to be a writer.”

That writer debuted in 1999 to instant acclaim with the disquieting The Intuitionist, set in an unspecified midcentury Gotham, a noir metropolis straight out of Jules Dassin and Fritz Lang. In its conceit, the world of elevator inspectors is divided between rival schools: Empiricists, who work by collecting data and making methodical observations; and Intuitionists, a minority of gifted inspectors who have a second sight that allows them to read elevator mechanics intuitively—an ability scorned and feared by the dominant faction. The novel follows Lila Mae Watson, a member of the Department of Elevator Inspectors, as she tries to solve the case of a suspicious crash, and also untangle the mysterious aphorisms of one James Fulton, whose gnomic text, Theoretical Elevators, may provide clues to a secret about its author and the nature of Intuitionism itself. It’s impossible not to like Lila Mae, a black woman occupying a role stereotypically identified with the square-jawed private eye, who uses her cool and wits to navigate this murky underworld and stay one step ahead of the men trying to frame her. Part of the fun is in the writing itself. Whitehead’s prose oscillates playfully between the pulpy, telegraphic neo-noir à la James Ellroy and the allegorical ruminations of Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man.

This gives the novel a slippery feeling, a cool detachment that makes it easier to admire than to love. It’s as though Whitehead built that book on the principles of stealth technology, every facet rigorously designed to achieve what it is also about: a game of camouflage and detection, the irony of invisibility in plain sight. His interest in unstable visibility suggests the theme of racial passing, a concern with a long history in the African-American novel. As the scholar Michele Elam pointed out, The Intuitionist can be read as “a passing novel in both form and content.” The familiar hard-boiled detective plot turns out to be merely a lure, a skin-thin surface masking a speculative novel of ideas.

As a first novel, The Intuitionist registered as a shot across the bow, as though Whitehead were daring readers to box him in. It was also a first glimpse of what has since become something of an authorial signature: an ironic deployment of genre as a mask for an eccentric but also cutting vision of American culture. It’s an approach that can remind one of Thomas Pynchon in novels like The Crying of Lot 49 (critics have compared its heroine Oedipa Maas to Lila Mae Watson) and Inherent Vice; or to the filmmaking of the Coen brothers, with their affectionate but sinister parodies of Hollywood noir in Barton Fink or Fargo. Like them, Whitehead delights in recasting the iconography of Americana, troubling its conventions and clichés by pressing them to their limits, and releasing that energy in the form of bleak satire and an impassive attitude toward violence.

In 2008, novelist Charles Johnson published an essay in The American Scholar titled “The End of the Black Narrative,” in which he argued that the history of slavery in America had become a crutch for understanding any and all experiences of black life—that at the dawn of the twenty-first century it had “outlived its usefulness as a tool of interpretation,” and should be discarded in favor of “new and better stories, new concepts, and new vocabularies and grammar based not on the past but on the dangerous, exciting, and unexplored present.” It’s an argument that has analogs in academic circles as well, where a movement around “afro-pessimism” has prompted debates in recent years over whether contemporary black life can ever transcend the historical experience of slavery. Whitehead hasn’t read the essay, but he says the argument makes sense to him if it means black writers need to have the freedom to write whatever and however they want. (He resists attempts to theorize his own work, and it’s clear he’s fairly allergic to the scholarly efforts to categorize his literature. He’s an excellent parodist and, whether aiming his wit at the sophistications of academic vernacular or the flummery of marketing lingo, he’s a master at deconstructing jargons. He once opened a talk at the Du Bois Institute at Harvard by delivering a compelling close reading of Flavor Flav’s “Can’t Do Nuttin For Ya Man” at the lectern.)

Yet his work has been viewed along these lines. His 2009 coming-of-age novel, Sag Harbor, follows a group of “bougie” black kids as they try to survive the summer of 1985 in the black enclave their parents have carved out in the Hamptons. A good part of the comedy revolves around the ways the main character, Benji Cooper, and his friends try and fail to act “authentically black”: city boys with toy BB guns awkwardly grasping at gangsta status. Reviewing the novel, journalist and cultural critic Touré, known for popularizing the term “post-blackness,” inducted Whitehead into a constellation of figures opening up the scripts of blackness: “now Kanye, Questlove, Santigold, Zadie Smith and Colson Whitehead can do blackness their way without fear of being branded pseudo or incognegro,” he declared.

“Post-blackness” should not be confused with the “postracial.” “We’ll be postracial when we’re all dead,” Whitehead quips, alluding to Zone One (2008), in which his hero, an Everyman nicknamed Mark Spitz, is part of a sweeper unit clearing out the undead in post-apocalyptic downtown Manhattan. In fact, no one has more deliciously julienned this particular bit of cant. In a 2009 New York Times essay, “The Year of Living Postracially,” Whitehead offered himself to the Obama administration as a “secretary of postracial affairs,” who like the hero of his 2006 novel Apex Hides the Hurt, will rebrand cultural artifacts to meet new societal standards. “Diff’rent Strokes and What’s Happening!! will now be known as Different Strokes and What Is Happening?” he suggested, and Spike Lee’s Do The Right Thing would be recast with “multicultural Brooklyn writers—subletting realists, couch-surfing postmodernists, landlords whose métier is haiku—getting together on a mildly hot summer afternoon, not too humid, to host a block party, the proceeds of which go to a charity for restless leg syndrome…” The essay suggests the influence of Ishmael Reed, whose hallucinatory satires mine the absurdities of racism for comic effect, highlighting how their surreal and grotesque contortions are refracted in language and sublimated in collective phantasmagorias: television shows, music videos, and the movies.

The critic James Wood has complained about a “filmic” quality in Whitehead’s writing. It is undeniable—but younger readers may find that that quality is its own kind of literacy, a clear picture where Wood sees only static. Rightly or not, there is something contemporary and vivid in Whitehead’s direct apprehension of the way lives are overdetermined and bound by chains of mediated images. It’s a gambit that has surfaced as a question for the contemporary novel before: David Foster Wallace famously worried that television had repurposed irony to commercial ends, defanging it as a weapon in fiction. Whitehead has drawn just the opposite lesson, wagering that irony not only sustains the postmodern novel—but that it can even deepen the stain of allegory.

Can this ironic method successfully take on American slavery? It might seem intimidating, perhaps even overwhelming, to write about a subject where the stakes feel so high. In recent years, the history of slavery, never far from the surface of American life, has seeped back into popular consciousness with renewed urgency. On television, Underground, which debuted this spring, follows the fugitive slave trail; and this past spring The History Channel remade Roots, the groundbreaking 1977 miniseries based on Alex Haley’s novel. On film, black directors are also thrusting slavery to the fore, notably Steve McQueen in 12 Years a Slave (2013) and now Nate Parker’s The Birth of a Nation (2016), about Nat Turner’s rebellion. This year has also brought at least two other novels that will frame the reception of Whitehead’s: Yaa Gyasi’s Homegoing reconsiders how African identities interlock but also diverge from the “black narrative”; Ben H. Winters’ Underground Airlines imagines a counterfactual history in which the Civil War never took place, and bounty hunters roam a contemporary United States seeking runaways. And all this still pales before the inevitable comparisons with major writers on the same theme. Whitehead anticipates these questions, and instantly brushes aside comparisons. “You have to do your own thing, right? Morrison”—that’s Toni Morrison, Litt.D. ’89—“already wrote Beloved; you’re not going to compete with that. I have to write the book that makes sense to me, that’s entirely my own vision.”

The Underground Railroad follows Cora, a slave on a cotton plantation in Georgia, as she makes a break for freedom. She becomes a runaway, a “passenger” who must elude capture as she makes her way northward on the famous Underground Railroad—in Whitehead’s conceit, made literal rather than metaphorical. “When I was a kid I always thought it was a real railroad,” he says with a flashing grin. It’s a testament to the power of metaphor, and, like the ghost in Morrison’s Beloved that haunts the former slaves of Sweet Home plantation even as they try to recreate their new lives in freedom, it marks an assertion of the novelist’s supreme freedom: the freedom that allows fiction to breathe and stand on its own, and writers to carve out a personal dimension within material fraught with communal and ideological strictures.

“When I was a kid I always thought it was a real railroad,” he says with a flashing grin.

If The Underground Railroad seems to give in to the inescapable pull of “the black narrative” which Whitehead had been celebrated for evading, the new novel isn’t as new it may appear. “This project has been on my mind for at least 10 years,” Whitehead says. “I started thinking about it around the time I was doing John Henry Days but I set it aside. I didn’t feel like I was ready yet to tackle it, the way I was writing then…I’m much more into concision now, in my writing, and I think this book needed that.”

For it, Whitehead did a good deal of research—looking to Eric Foner’s Gateway to Freedom (2015) to depict the cat-and-mouse game between slavecatchers and freemen scouting for runaways along the docks of New York harbor, and reading the Works Progress Administration’s collection of slave narratives for material details of slave life. But above all, Whitehead drew on the rich literary history to which he is adding a new chapter, refashioning famous scenes in Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin and Harriet Jacobs’s Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl—especially her account of seven years spent hiding in an attic (a passage he singled out as having profoundly marked him when he read it in college). The ominous figure of the slavecatcher Ridgeway suggests more recent antecedents. Cormac McCarthy’s Blood Meridian, with its vision of bounty hunters chasing scalps on an American frontier steeped in apocalyptic gore, echoes in Whitehead’s chronicling of the orgiastic violence that haunts the hunting grounds of slavery.

The novel explicitly links slavery to the engine of global capitalism. The theme has gained prominence in recent years, notably through works like River of Dark Dreams: Slavery and Empire in the Cotton Kingdom (2013) by Walter Johnson and Empire of Cotton: A Global History (2014) by Sven Beckert (both of Harvard’s history department), which have enlarged the context for our understanding of slavery and resuscitated neglected arguments put forth at least a generation earlier by black Marxists like Eric Williams and Cedric Robinson. The idea of a capitalist drive behind slavery always seemed intuitive to Whitehead, he says. “Being from New York,” he suggests, “you can see the drive for exploitation all around you. It just always seemed obvious to me.”

Rather than centering on one site or aspect of slavery, The Underground Railroad presents readers with a kind of composite. The novel proceeds episodically, with each stage of Cora’s voyage presenting a variation on the conditions of enslavement and emancipation. Caesar, a fellow slave on the Randall plantation who encourages Cora to run away with him, compares their predicament to that of Gulliver, whose book of travels his more lenient master has allowed him to read. He foresees a flight “from one troublesome island to the next, never recognizing where he was, until the world ran out.” This sense of variation on a theme—with no exit in sight—creates a sense of blind forward propulsion without “progress”: scenes of medical experimentation that recall the infamous Tuskegee Syphilis Studies appear side by side with those of coffles, auction blocks, abolitionist safe houses, as well as the vision of Valentine farm, a haven in Indiana founded by a successful mixed-race free black who believes that hard work and exposure to high culture will secure the acceptance of his white neighbors. “I wanted to get away from the typical, straightforward plantation,” Whitehead says. His novel doesn’t seek to reenact history, but rather to imagine and represent simultaneously the many hydra heads of a system designed to perpetuate the enclosure and domination of human beings.

The genre of fugitive-slave narratives has long been haunted by sentimentality. As the scholar Saidiya Hartman has suggested, the use of the pain of others for readers’ own purification or enlightenment—or at worst, entertainment—is a deep problem for this genre. Many have argued that the truth of slavery can only be understood first-hand. William Wells Brown, who published an account of his own escape to freedom in 1847, famously asserted that “Slavery has never been represented; Slavery never can be represented.”

To write about slavery is to face head on this risk of representation. The Underground Railroad can feel at times over-represented, almost too explanatory—seeking at every turn to demonstrate how this or that aspect of slavery worked, flagging a character’s motivations by relating them back to that system. There’s precious little room for characters to be something other than what they appear to be, something more than allegorical props. At one point, Cora, staying at a temporary haven in South Carolina, goes up to the rooftop to look out over the town and up at the sky. The scene’s only function seems to be to give the reader a chance to overhear some of her thoughts and hopes, something of who she is when she is not engaged in the business of trying to stay alive. Despite Whitehead’s best efforts, Cora remains sketched rather than known, a specter seen through a glass darkly. She is a Gothic woman in the attic, haunting the national consciousness, a symbol more than a person. It’s a connection Whitehead makes explicit: “Now that she had run away and seen a bit of the country, Cora wasn’t sure the Declaration described anything real at all,” says his narrator. “America was a ghost in the darkness, like her.”

Yet there is something new and perhaps unprecedented in the way Whitehead has reasserted the agency of black writers to reconstruct “the black narrative” from within. Whitehead interleaves The Underground Railroad with invented runaway-slave advertisements by planters seeking to recover their property. But in the last one, the hand of the author and that of his protagonist are momentarily overlaid, as though we are reading an advertisement Cora has left us, “written by herself,” as the subtitles of slave narratives habitually put it. “Ran Away,” reads the title and declares below: “She was never property.” The device harnesses the power of fiction to assert impossible authorship, to thrust into view the voice that could not have spoken—but speaks nonetheless. Cora becomes, in the last instance, a mirror not only for the drama of slavery, but for the whole problem of writing about slavery: a vector that points away from something unspeakable and toward something unknown—and perhaps unknowable.

Interestingly, John Henry Days, the book by Whitehead that deals most substantially with the history of Black America, is also almost certainly his least-read. Its hero, J. Sutter, is a freelance writer drawn from New York to an assignment in Talcott, West Virginia: the U.S. Postal Service is hosting a festival celebrating a new John Henry commemorative stamp. Whitehead uses the mythical man and J. Sutter’s pursuit of his meaning to transect the sediment layers of black history. His novel starts at the surface of a media-frenzied America circa 1996, simmering with racial unease and tortuous political correctness, then tunnels down to the labor of steel driving gangs in the 1870s. Along the way, it stops to recast figures like Paul Robeson or rewrite the rioting at Altamont Speedway. Suggesting another history, or set of histories, behind the one we think we know, Whitehead poses the thorny problem of how to interpret the stories we inherit.

In The Grey Album, his collection of essays on black aesthetics, Whitehead’s friend Kevin Young has advanced the idea of the “shadow book”—certain texts which, for a variety of reasons, may fail to turn up: because they were never written, because they are only implied within other texts, or simply because they have been lost. One might add to this a category of books that are eclipsed. For John Henry Days, it was Infinite Jest. Bothare postmodern leviathans, ambitiously unwieldy and bursting with insight, indelibly products of the 1990s. Yet Whitehead’s book has never acquired the kind of cult following that David Foster Wallace’s has. Published in 2001, it seems to have been eclipsed at least in part by historical events (though it can’t have helped that Jonathan Franzen wrote a self-absorbed review for The New York Times that ignored any discussion of race, a stupefying lacuna; Whitehead says that Franzen in fact later apologized for it). If John Henry Days is the “shadow book” of the nineties, the other great masterpiece behind the masterpiece everyone knows, it is also a powerful complement to this new novel on slavery. In time it may be recognized that these books are among Whitehead’s defining achievements, capturing the black experience in America with a wide-angle lens, carrying both its mythic and realistic truth, and delivering it over the transom into the maw of our digitally mediated Internet age.

“You have to do your own thing, right? Morrison already wrote Beloved. You’re not going to compete with that.”

In the meantime, with The Underground Railroad gone to press, Whitehead has been catching up on the reading he loves. He’s reading a lot of crime fiction, Kelly Link’s short stories, and he’s well into the latest Marlon James novel. His daughter is an avid reader of comics, so he’s catching up on those as well. Asked what he might work on next, he answers that he’s still focused on promoting the new book, of course—but possibly something about Harlem, something set in the nineteen sixties. After lunch wraps up, he heads down the block, walking smoothly, smoking a cigarette, back into the thrumming heart of the city.

“You are a New Yorker when what was there before is more real and solid than what is here now,” Whitehead writes in the opening pages of The Colossus of New York. A strain of apocalyptic foreboding, tempered by a refusal to sentimentalize trauma, courses through Colson Whitehead’s fiction. It’s present in the books he wrote even before 9/11. But the attacks of that day inevitably cloud the lyrical essays gathered in Colossus, a collection published in 2001, a time of disaster and mourning in the place he has always called home.

Yet unlike so much writing about New York, Whitehead’s deliberately shies away from emphasizing what makes it special and unique. Whitehead writes instead of the invisible cities that everyone knows and carries within memory, not necessarily the ones that still exist in brick and mortar. He writes about the universal qualities of arrival and departure, loneliness and haste. His second-person address to “you” contains within it the gentle pressure of Walt Whitman’s “I too,” from “Crossing Brooklyn Ferry.” Whitehead’s answer to the calamity of terrorism is to insist, like Whitman, on the unbreakable power of the city to transform the vulnerability of the huddled crowd into a heightened, even universal empathy.

“Talking about New York is a way of talking about the world,” Whitehead writes on the last page. True, but it is also a way of reflecting the world through one’s own experience of it. It seems not entirely a coincidence that elevators and underground trains, two of New York’s most iconic modes of transportation, are the symbolic vehicles Whitehead has invoked as he grapples with the wider meanings of America. Whether he is writing about the city he knows best, or the lives of characters in almost unimaginable circumstances, Whitehead has demonstrated time and again a remarkable capacity for turning what appear to be evasions into encounters, the historical arc we want to hide from into the narrative arc we can’t avoid. He is a writer who stands squarely in our present dilemmas and confusions, and suggests lines of sight no one else seems to have considered or dared to imagine.