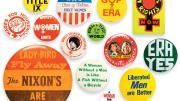

Tiny pins with their delicate metal fasteners still intact, some more than 100 years old, read “Votes for Women” and “I March for Full Suffrage” in faded letters. Some sit in miniature carrying cases, signifying, perhaps, that they once meant a great deal to someone. Newer pins use vivid hues and bolder fonts to match their more ambitious aspirations: “A woman’s place is in the House and Senate.” “Ann Richards for Governor—Texas.” “E.R.A.—YES.” A pin featuring Hillary Clinton, then campaigning for her husband, foreshadows this election year, in which a woman will appear as a serious contender on the presidential ballot—likely a distant dream to the suffragists of a century ago.

Political pins have been in use for at least 200 years, explains Kathryn Jacob, curator of the pin collection at the Radcliffe Institute’s Schlesinger Library; the oldest pins housed there date back to the movement for women’s suffrage, which will celebrate its centennial in 2020. The pins provide evidence of hard-won fights for political rights now often taken for granted; others recall battles that appear to have gone nowhere in 50, 60, 70 years. Says Jacob, “You look at some of these buttons and think, ‘Oh yeah, we’re fighting that fight all over again.’”

The largest set of pins—more than a thousand, from the 1960s and later—was donated by Bernice Sandler, one of the architects of Title IX, the federal law banning gender discrimination in education. As a graduate student in the 1960s, Sandler says, she was denied funding from her department because she was a woman. “I asked why I didn’t get a scholarship, and I was told, ‘Oh, we don’t give it to females, and you’re married besides.’ The belief was that women get married and therefore don’t need the scholarship. That was legal—before Title IX made it illegal.”

That was when Sandler decided to devote her life to the advancement of women’s legal rights. “At the time,” Sandler, now 88, remembers, “buttons were popular for all kinds of causes. Women who were working on women’s issues were all printing buttons.” She printed pins declaring “Uppity Women Unite” and “God Bless Title IX” and handed them out at all her talks: “I must have given out 7,000 of them,” she says. “The pins were an easy way to talk about women’s rights because they were funny. They made it easy for men to care about women’s issues without being viewed as dour or threatening.”

She scattered them over all the surfaces of the Cosmos Club, an elite Washington social club that didn’t allow women to enter through the front door (a policy it would end, begrudgingly, in 1988, after the city found it in violation of anti-discrimination law). Once, she recalls with delight, a server at the club asked her for a handful of pins, which, she learned later, he planted on the urinals of the men’s bathrooms.