Blanche (Ames) Ames and her husband, Oakes Ames, professor of botany at Harvard and director of the Arnold Arboretum, were in the middle of the Yucatan jungle when their car stalled. As Oakes and the driver stood by helplessly, Blanche pulled a hairpin from her chignon, extracted a bullet from her revolver, and set to repairing the carburetor. She started the car—to this day, no one knows how—and the expedition continued.

The intrepid mechanic, daughter of one Civil War general and granddaughter of another, had graduated as president of her class at Smith College in 1899 with a degree in art history, a diploma from the art school, and the dream of becoming a professional artist. (“My ambition is soaring on the art line,” she told her parents. “You see I am puffed up and my fancies take wild flights.”) When she met Oakes Ames, A.B. 1898—no relation, but a friend of her brother’s—he began courting her with gifts of “the queerest orchids,” as she described them to her mother. After they became engaged, he presented her with a microscope so that she could examine and draw the botanical specimens he collected.

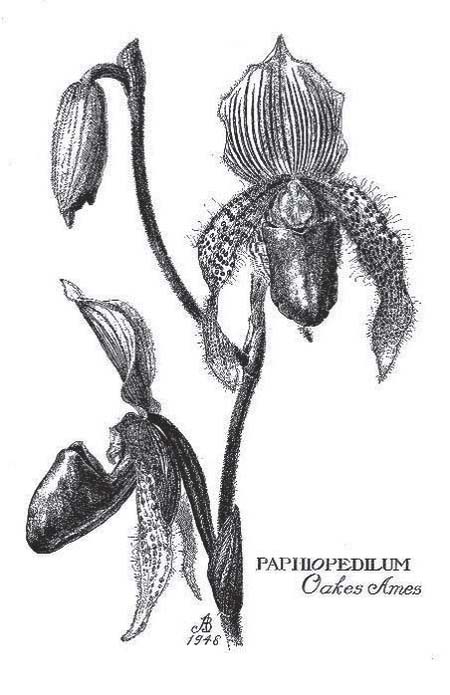

Illustration by Blanche Ames

Blanche Ames was soon renowned as the foremost American botanical illustrator of the age. Using the microscope and another optical device, a camera lucida, she captured the intricate form of orchids: the delicate root hairs and rhizomes, the anther cap perched over the pollen bundles, the succulent pseudobulbs. Thanks to dark shadowing and crosshatch highlights, her elegant pen-and-ink drawings boldly depict the plants against the white page. They are at once scientifically exact and artistically brilliant.

Blanche illustrated all seven volumes of Oakes’s seminal work Orchidaceae: Illustrations and Studies of the Family Orchidaceae (1901-1922). The orchid family had been considered a crucial case study of the theory of evolution by natural selection ever since Charles Darwin published his Fertilization of Orchids in 1862, speculating that orchids and their pollinators had adapted to each other or “co-evolved.” But research on orchids was hampered by pervasive confusion over the proper way to classify them. Oakes undertook a comprehensive overhaul. By the end of his life he had become the most celebrated orchidologist in the world.

Blanche shares the credit for placing orchid study on a firm scientific foundation, and not only for her incredibly precise drawings. During their 50-year marriage, she was more than an illustrator; she was her husband’s co-investigator, and he justly referred to her as his “colleague”: they traveled together to the Caribbean, the Philippines, and Central and South America in search of specimens. Oakes is acknowledged as the discoverer of more than 1,000 new species. Many of these he found side-by-side with Blanche.

Once, in Rio de Janeiro, Oakes learned of a Brazilian orchid that had been discovered decades earlier and sent abroad to the foremost authority on the area’s orchids. The specimen was lost en route; its only ghost was a watercolor drawing that had been made before it was sent. Because the drawing did not show enough detail to classify the orchid, and no further specimens had been found, the species remained in a kind of scientific limbo. Returning later from an expedition to Brazil’s Mount Itatiaia, Oakes and Blanche found a large fallen tree blocking their path. Growing on that tree was a single orchid—incredibly, it was a specimen of the lost species. Blanche, not Oakes, was given the discoverer’s honor of the taxonomic name: Loefgrenianthus blanche-amesiae.

Oakes’s remarkable herbarium, now part of the Harvard University Herbaria, was another joint effort. Most of the sheets include plants dried and pressed by Blanche, as well as her sketches and watercolors of the living specimens, together with Oakes’s notes, photographs, and journal clippings. Comprising thousands of pages, the herbarium remains a valuable resource for botanists—especially the copies Blanche made, during a visit to Berlin in 1922, of the herbaria sheets of Rudolf Schlechter and Rudolf Mansfeld of the Berlin-Dahlem Herbarium. When the originals were destroyed during the bombing of the city during World War II, Blanche’s copies became the only remaining documentation of some species these botanists had discovered.

Courtesy of the American Orchid Society

Many research papers published in the Harvard series Botanical Museum Leaflets were also graced by her drawings. She supplied the orchid illustrations for the first posthumous edition of the Manual of the Botany of the Northern United States by Harvard professor Asa Gray, the foremost American botanist and Darwinist of the nineteenth century, and illustrated the books of other botanists as well. The American Orchid Society commissioned her to design its medallion (above): a Native American, modeled on her son Oliver, gazing upon a branch of orchid blossoms. Today, her motif adorns the seal of the society as well as its gold medal of achievement, which was first awarded in 1924—to Blanche and Oakes Ames.

A woman of many talents, Blanche Ames was also a sought-after portrait painter, an inventor who held four patents, and a political activist engaged in the struggle for women’s suffrage and birth-control rights. But her greatest impact was upon the scientific study of orchids, a field still considered central to the study of evolution, especially for investigations of species interactions. Her botanical illustrations exquisitely embody Darwin’s view of orchids and their parts as “multiform and truly wonderful and beautiful.”