In 1928, Frederick Clifton Packard Jr. ’20, head of Harvard’s public-speaking department, improvised a cutting-edge audio-recording studio in one of the Yard’s oldest buildings, installing a telegraphone in Holden Chapel. The device, about the size of a small radio and roughly resembling a typewriter, was deemed “decidedly unimpressive in general appearance” by The Harvard Crimson, though “ingenious and almost uncanny” in its power to capture speech. Most thrilling, and disquieting: “The record may be preserved for eternity or simply be rubbed out.”

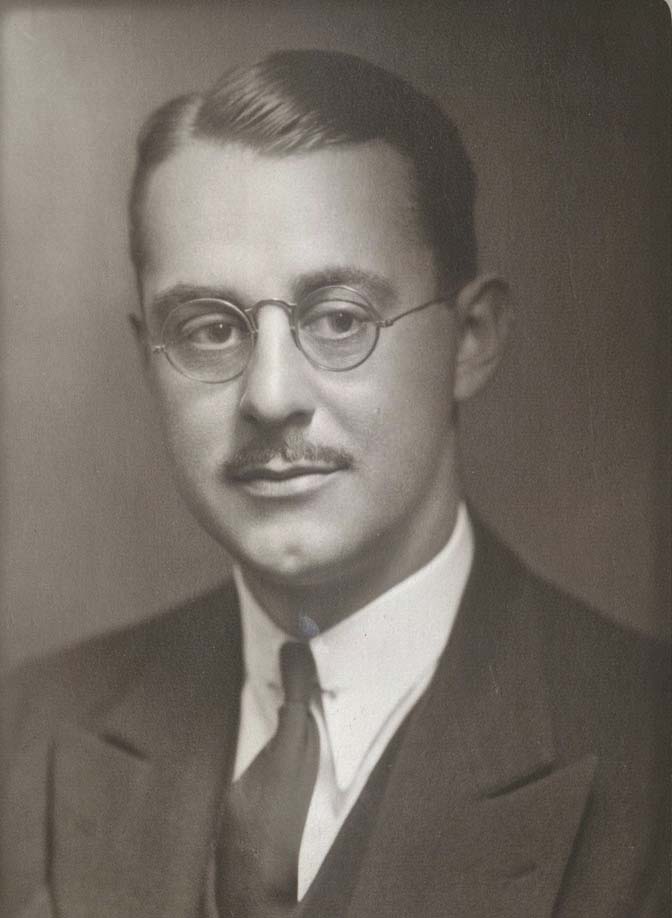

Frederick C. Packard, head of Harvard’s department of public speaking, envisioned a library where visitors could enjoy both “the printed book and the ‘talking book.’”

Photograph courtesy of the Woodberry Poetry Room

Packard had always loved the spoken word: he produced amateur plays around Boston while at college, and afterward pursued an acting career in New York and Europe before returning to his alma mater to conduct linguistics research and help students and faculty with speech impediments. He also loved literature, especially the way it sounded, and at studio set-ups scattered around campus—in the Germanic Museum, the Cruft Memorial Laboratory, the basement of Memorial Hall, and elsewhere—he pursued another of his eccentric projects: the Harvard Vocarium, one of the earliest commercial recording labels for poetry. Its first few records were released in 1933and featured T.S. Eliot, A.B. 1910, Litt.D. ’47, but slotted the future Nobel laureate in what seems today a peculiar lineup—alongside recordings of two Harvard professors reading from the Bible and Chaucer.

The Vocarium started up just as sound recording technology was disrupting literary mores surrounding poetry and performance. Though poetry’s association with voice is as old as the art itself, the rise of radio in the 1920s dramatically reconfigured that relationship. It had long been assumed that poets were not the best performers of their work, Lesley Wheeler writes in her book Voicing American Poetry, but broadcast media made trained, polished voices ubiquitous. Audiences became more invested in the concept of writers’ authentic presence, as conveyed by their idiosyncratic, physical voices. Author readings became more common, while verse recitals by amateurs and professional performers alike fell out of favor; in schools, pedagogical weight shifted from elocution to interpretation. It became integral to the careers of poets like Robert Frost ’01, Litt.D. ’37, and Edna St. Vincent Millay to share their work with listening audiences—he in public events; she over the airwaves.

Packard recorded whatever luminaries he could coax into a studio session while they were visiting campus: the now-famous voices of Tennessee Williams and Dylan Thomas, and others whose work in any format has grown obscure, like the political poet Muriel Rukeyser and 1938 Pulitzer Prize-winner Marya Zaturenska. But he also carefully cast professionals to read non-contemporary verse: English thespians Flora Robson and Robert Speaight were recruited to perform Shakespeare, and scholars pronounced whole albums of Anglo-Saxon and Latin poetry.

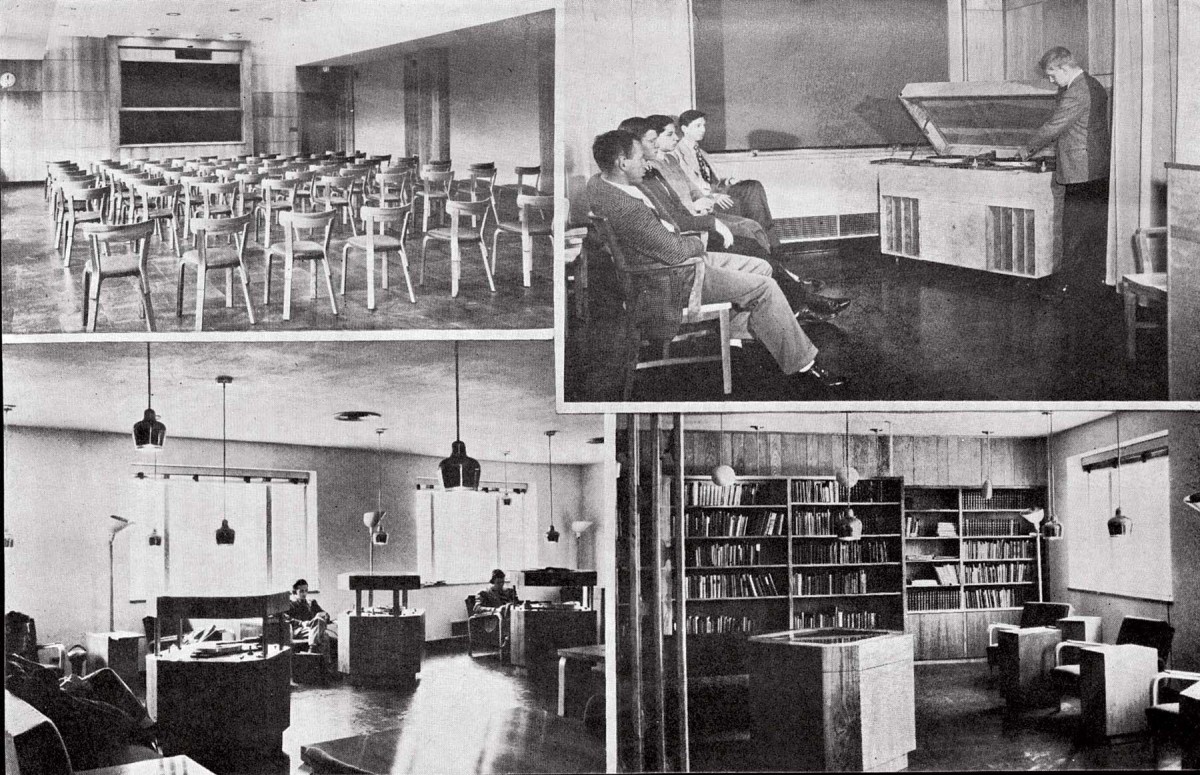

The Woodberry Poetry Room, designed by Alvar Aalto, opened in Lamont Library in 1949 (bottom row). Next door, the Lamont Forum Room (top row) featured a two-turntable playback for “group listening” and “poetry concerts.”

The Woodberry Poetry Room, designed by Alvar Aalto, opened in Lamont Library in 1949 (bottom row). Next door, the Lamont Forum Room (top row) featured a two-turntable playback for “group listening” and “poetry concerts.”Photograph courtesy of the Woodberry Poetry Room

Packard used his coinage “vocarium” to refer to an idea much more ambitious than his commercial label: he imagined a “library of voices” that preserved speech for posterity, a place people could actually visit to immerse themselves in words. One day, there might be “vocariums” in local schools and libraries all over the country. Fulfilling his dream of a space where the “talking book” could be appreciated alongside print text, the Woodberry Poetry Room was relocated to the recently opened Lamont Library in 1949. The space, specially designed by Finnish architect Alvar Aalto to emphasize listening, could accommodate 36 patrons at a central table and at auxiliary “listening posts,” where visitors could “browse”—eavesdropping at will on whatever others were playing at the time. Next door was the soundproofed Forum Room, where classes could gather for group listening sessions. (The “student motion picture group,” Ivy Films, also screened its first complete film there.) By 1950, the library had almost 500 discs in addition to its sizable book collection.

The Harvard Vocarium might be best known today for making the earliest recordings of American modernist poets like Robert Lowell ’39, Elizabeth Bishop, and Ezra Pound. “Recording technology allowed poets, to a certain extent, to model how free verse might sound,” says Woodberry Poetry Room curator Christina Davis. As William Carlos Williams entreated, in a 1951 reading at Harvard recorded for the Poetry Room: “Listen! Never mind, don’t try to work it out; listen to it. Let it come to you. Let it—sit back, relax...Let the thing spray in your face!” A ripple of laughter went through the audience. His reedy voice, almost wheedling, continued, “Get the feeling of it; get the tactile sense of something, something going on. It may be that you may then perceive—have a sensation—that you may later find will clarify itself as you go along. So that I say, don’t attempt to understand the modern poem; listen to it. And it should be heard. It’s very difficult sometimes to get it off the page. But once you hear it, then you should be able to appraise it. In other words! If it ain’t a pleasure, it ain’t a poem.”

Even now, long after these writers have been canonized, their sound retains the power to shock. “Once you hear Ezra Pound screaming and beating on a kettle drum—I mean, you’re just never the same,” enthuses Poetry Magazine editor and former curator Don Share. In one recording, he says, “There’s a little bit of laughter at the end. The people in the room got a kick out of the poem, and you can hear them laughing! Who would believe a thing like that?”

When Porter University Professor Helen Vendler was a graduate student at Harvard, women weren’t allowed in Lamont Library except in the summer, when that part of campus became temporarily co-ed. At the time, she didn’t especially like modernist poetry, and particularly disliked Wallace Stevens, Frost’s classmate, whose work “didn’t look like the poems I knew,” she told an audience at a Poetry Room event in 2012. But a friend visiting the Woodberry Poetry Room with her insisted on listening to him, and eventually, said Vendler, “Once I had become familiar with his voice, I thought of all the poems as mysterious packages that had something for me inside.” As she recounted in an interview for The Paris Review, “Suddenly, this voice was unspooling. I didn’t even know what the poem was about. All I knew was that there were these wonderful lines that I would never have willingly walked away from.”

The writer in question harrumphed, in a 1953 letter, that “I have always disliked the idea of records,” and claimed that his Harvard visit had been taped without his consent. Still, perhaps grudgingly, Stevens marveled at the communion with poetry that the Vocarium encouraged. “On the one occasion that I visited the Poetry Room in the new library at Cambridge, there were a half-dozen people sitting around with tubes in their ears,” he wrote, “taking it all in the most natural way in the world.”

The Harvard Vocarium label stopped publishing in 1955. Its exact cause of death is ambiguous—the venture was only sporadically documented—but funding had always been difficult to come by, and according to a 2011 interview with his granddaughter, Josephine Packard, Packard had begun to experience symptoms of early-onset Alzheimer’s. But he continued to gather and make recordings, and throughout the 1950s and 1960s, Poetry Room director John (“Jack”) Lincoln Sweeney assumed Packard’s mantle. He made recordings of poets from Sylvia Plath to Audre Lorde, and established a tradition of Harvard curators collecting the voices of the great writers of their moment, building sonic time capsules of contemporary literary culture.

When Don Share became curator in 2000, he set about digitizing these holdings. “My office was filled with these discs and tapes, just stuffed to the windows, and nobody knew what they were,” he recalls. Others at the library dismissed them as unplayable junk beyond repair, telling him to toss it all, to free up some space—“and of course I stockpiled every bit of it.” More than that: Share put out a call within the University, and then further afield, for Vocarium and Harvard-related materials. “Underwriting every poem was a collection of objects, correspondence, bits and pieces of audio, sometimes other things. I felt like it was my job to assemble that constellation.”

People from all over the world mailed him audio objects, sometimes only loosely related to Packard. The Poetry Room had to acquire special equipment to play some of the stuff, including a hand-built tape recorder and bamboo needles. “You just never saw such a strange collection,” he says now, chuckling.

Poetry Room curator Christina Davis (left) and assistant curator Mary Walker Graham

Photograph by Stu Rosner

Since 2013, curator Christina Davis and assistant curator Mary Walker Graham have been taking inventory of what’s formally known as the Frederick C. Packard Jr. Collection, the founding sound archive of the Poetry Room. Sitting in slate gray boxes neatly stacked in Davis’s office, its contents are surprisingly unruly—some 2,500 objects in all. Of these, 1,500 are vinyl and shellac discs—mostly overstock from Packard’s label—which can be heard on a record player. There are also odds and ends from the recording process: the original recordings created in the cutting room, on lacquer discs; the series of metal parts called masters, mothers, and stampers, used in manufacture; various test pressings, B-sides, and recording sessions which never made it to publication. On one disc, Marianne Moore can be heard asking Packard about whether she’d been speaking too quickly. On another, Weldon Kees—a writer and abstract expressionist painter, who disappeared in 1955—stops reading with an abrupt, “Sorry, kill it!” (“We gasped when we heard that,” says Davis.)

Davis likens the collection to an archive with several incarnations of a book—its final published edition, but also copyedits and galleys, and a stray handful of orphaned pages of the original manuscript, and then, perhaps, a reading with interesting annotations from generations of passing visitors.

“And not just one book,” adds Graham. “Hundreds of books in fragment form.”

“With no living editor,” finishes Davis. “So the mysteries are many.”

Their survey revealed the collection’s surprising breadth, including hundreds of non-Harvard Vocarium discs. Packard collected recordings of writers and performers working in Haitian Creole, Afrikaans, Danish, Yiddish, and Gaelic; he recorded rehearsals of Orson Welles’s radio plays, Mexican folk songs, and works in Sanskrit by the Indian playwright Bharati Sarabhai. Packard’s love of voiced literature had global range, says Graham. “I think if he could have, he would have recorded in every language.”

His desire to document the spoken word went well beyond the arts. In addition to the students he recorded for his speech clinic, Packard captured addresses by visiting dignitaries; he also acquired memorials, sermons, and many hours of Japanese language lessons. One record, labeled “hypophysectomy—rat. parapharyngeal approach, to accompany a 16 mm color film of that title,” contains audio from a medical surgery. “Packard seemed to see an opportunity, with the introduction of sound recording, to almost defy discipline,” says Davis.

The Poetry Room will release a finding aid for this collection over the summer, a project that sounds simple on its face: it’s an inventory of the holdings, linked to the Harvard Library catalog, alerting researchers to the existence of its various and sundry treasures. But the fragility of various items posed a physical challenge, requiring custom-built enclosures to keep them safe—and the sheer eclecticism of the collection posed an organizational one.

The stewards also faced a nagging ethical and epistemological dilemma: how to deal with the various discs that were too delicate to be played. Some objects had markings, paper sleeves, or related ephemera that gave some hint as to what audio might be on them, but the curators had been surprised before. “If you say, ‘Unknown author, unknown title, unknown year,’ that thing will never get played,” Davis says. “On the other hand, if you say too much, you mislead people.”

“We’re a good team,” says Graham. “Because I tend to err on the side of, like—the only thing we can say about this is that it’s a 13-and-a-quarter-inch disk that’s lacquer on metal and has some edge damage. And Christina’s more like, ‘But I think we could probably say…’”

“We’re like a cop show,” Davis confirms.

“Processing the collection is about finding the balance,” says Graham.

Because of its fragility, the survey of the Packard collection is, for now, necessarily incomplete—as is the even more ambitious project of making all of the audio listenable. But the curators hope the finding aid will alert scholars of the possibilities for further investigation. As Davis puts it, “It’s not the key to the door—it’s building the door frame.”

“Y’all can hear me, right?” tossed off the poet Tyehimba Jess, sauntering away from the podium at a Poetry Room event last November. At first he declined the hand-held mic Davis proffered. In an undertone, she explained that they needed a clear, direct feed. “Oh, for the camera, huh?” he grinned. At Poetry Room events, posterity is the other, invisible audience. Davis plans with the archive in mind.

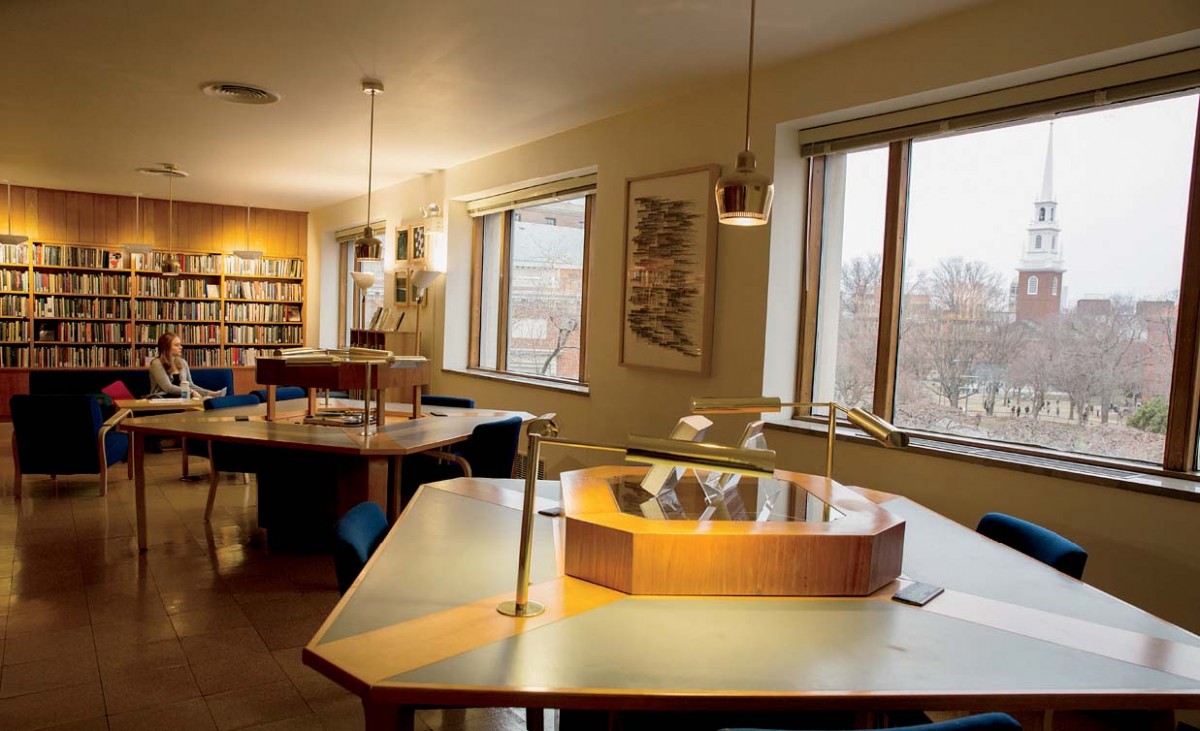

Views of the Woodberry Poetry Room today, refurbished in 2006, with laptop tables added to the two remaining Aalto-designed consoles.

Photographs by Rose Lincoln/Harvard Public Affairs and Communications

Especially in recent months, she’s taken an experimental approach to programming. Last semester’s calendar included a conversation about criminal-justice reform, a workshop in which attendees collectively translated a poem by a Cuban dissident, and a “protest-writing session,” in which the public was invited to make posters and banners together over snacks. But occasionally, the room hosts the odd Packardesque session. No conceptual twists: just the writer and the work. The guest of honor is seated at a table in front of a microphone. Attendees sit at eye level and nearby, in a crescent of comfortable chairs. These events feel less like “readings”—stiff and pseudo-liturgical, the community duly gathering to reify high literature—than like a much more basic pleasure: being read to. The recording sessions do look and feel a little like a throwback to a long-gone time, but it also has a way of distilling the experience of the poem. “Oddly, by putting a big, slightly retro-looking microphone in front a human being,” says Davis, “your attention gathers around the voice, and less around the total performance and the physicality.”

Video encodes more sensory data than audio. Someone could watch video of, say, Rowan Ricardo Phillips’s reading in 2014, and note what he was wearing, the Starbucks cup at his elbow, the snow falling outside. But no volume or density of additional information can put a perfect seal on the historical record. Questions gust in through the cracks. Who was the woman who came in late? Who held the camera, and what did that person do to prompt the poet to make eye contact—first warily, then warmly, like sharing a private joke?

Davis makes event audio available on the Poetry Room’s online Listening Booth, and puts a copy in in Harvard’s digital repository; sometimes she also uploads the video on YouTube. Her time with the Packard Collection has made her wonder if she ought to keep files in some second format, perhaps physically. She’s leery of repeating the mistakes of the past. WAV (Waveform Audio Format) files are standard now, and can be played by almost any personal computer, but one day that equipment might be scarce.

These days, Packard’s listening posts take the form of earbuds and iPads, loaded up with digitized audio files, screens glowing, though the curators sometimes bring out the actual artifacts, by advance request, for individual study. Davis likes to say that the Woodberry Poetry Room’s archive tells the history of transfer. Through it, one could trace the history of recording technology: voices were reincarnated from discs to reels, and then to cassettes, then to CDs—“surprisingly fragile,” she adds—and now to digital files. Each curator sought to preserve the Vocarium audio on what was then the state-of-the-art format; each curator freely exercised editorial discretion about what to copy over, whether due to a format’s physical limitations or their own aesthetic preferences. Sometimes records were altered in transfer, the original tracks re-ordered or left off. One reel she and Graham found seems to contain a recording of Robert Frost, and also, inexplicably, a lute performance.

It’s very humbling, Davis says, to think that the future may laugh at you: “Every generation is arrogant in thinking what it invented is going to last.”