In May, 15 UMass Lowell seniors, graduation day in sight, push off from the city’s Bellegarde Boathouse for an afternoon of kayaking on the Merrimack River. Here the waterway, first harnessed to power textile mills in the 1800s, is about a thousand feet wide and smooth, thanks to the Pawtucket Dam. Paddling upstream, toward New Hampshire, the group soon turns off to duck, single-file, under the granite arches of the historic Stony Brook Railroad Bridge, in North Chelmsford.

They enter a calm section at the confluence of river and brook, surrounded by reedy banks and sun-dappled trees. A great blue heron perches on telephone wires. Bird songs fill the air. Everyone stops to listen. “This is a great time to be here,” says trip leader Kevin Soleil, assistant director of outdoor and bicycle programs at the university’s recreation department. “The water is really high because of all the rain, and the birds are migrating through. It’s also a great time to find a piece of trash and pick it up—like those cans and plastic bottles floating over there.”

There are wilder sections of the Merrimack. At 125 miles, it snakes through 30 cities and towns: from rural Franklin, New Hampshire, down into the former industrial hubs of Manchester and Nashua, then swings east into Massachusetts through Lowell, Lawrence, and Haverhill to Newburyport and the Atlantic Ocean. (To the north, the Contoocook River Canoe Company offers scenic river outings from the town of Boscawen, New Hampshire.)

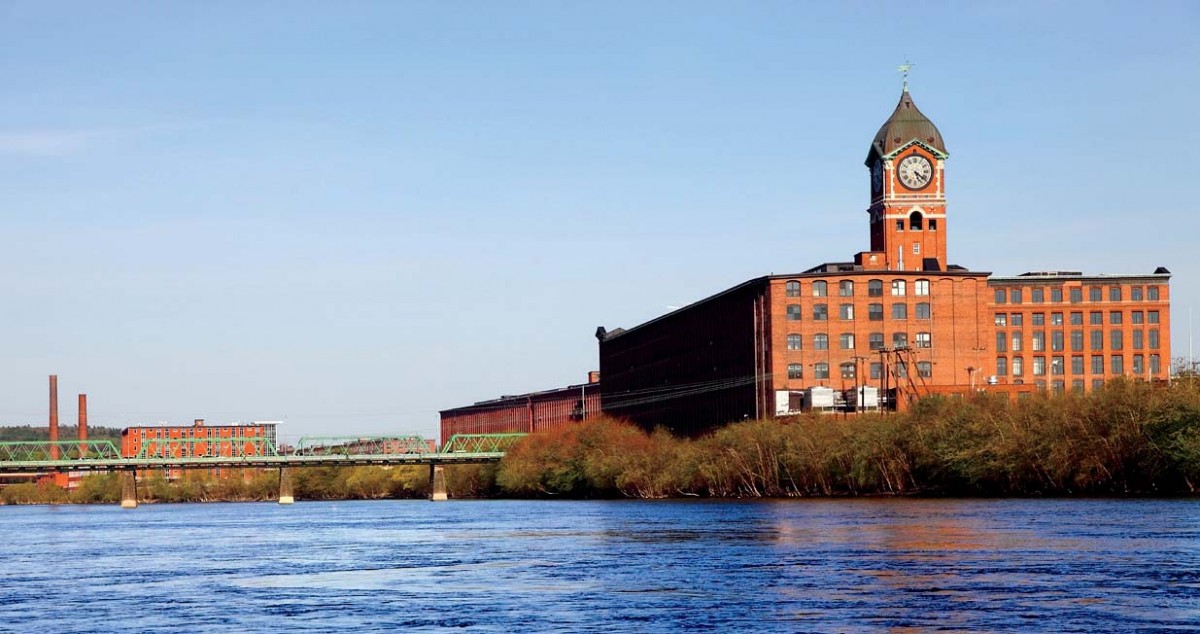

The Ayer Mill clock tower, restored in 1991, still presides over Lawrence.

Photograph by iStock Images

Two urban stretches in Massachusetts hold a different sort of fascination: in Lowell, it’s the six miles from the boathouse to Tyngsborough; in Lawrence, it’s a paddle that begins near the Great Stone Dam. There the Merrimack is “ ‘beautiful river meets urban development.’ A real mixed bag,” says Soleil, who grew up in Nashua, another former mill city. His Irish and French-Canadian ancestors were among the thousands of immigrants who flocked to the Merrimack Valley for work, first in the water-powered factories, then in those fueled by steam. “My grandmother grew up in Lowell and worked as a teen in the mills of Manchester,” he says. “And yet you go up hiking in the White Mountains in the Pemigewasset Wilderness, and you drink from Pemigewasset River headwaters—and that’s this water,” he says, gesturing out over the Merrimack. “It’s an urban waterway, but it’s connected to these places we think of as pure wilderness. And then you’ve got the history. This was the birthplace or cradle of the American industrial revolution.”

In Lowell and Lawrence that legacy still dominates the downtown landscapes. For paddlers on the river, architectural artifacts—smokestacks, railroad crossings, and dams—can loom large. At the same time, roving the river’s creeks and crannies reveals a “vibrant ecosystem,” Soleil reports. Hawks and eagles, beavers, turtles, woodchucks, deer, and foxes live here, too, despite the array of pollutants—industrial and household waste, raw sewage, cars, tires, TVs, and furniture—that have continuously endangered the river for more than two centuries.

Nevertheless, many people increasingly seem to view the river as an asset, as something to be enjoyed—and protected. The few urban parks are well used. More public access points and trails are planned, and houses and condominiums along the river are coveted, many marketed as “riverside.” A rising number of visitors (last year more than 2,000) are taking trips on boats from the UMass Lowell Kayak Center at the Bellegarde Boathouse, which rents kayaks, canoes, and stand-up paddleboards through September 5. Soleil and his staff also give boating lessons and run guided paddling tours for families, along with outings at sunset or by moonlight. A Saturday 11 a.m. shuttle carries paddlers and their gear from the Lowell boathouse to a launch in Tyngsborough: the trip back downstream takes between two and four hours. “People are often surprised when they get out on the water that the river’s as beautiful as it is,” says Soleil. “They’re expecting all the bad things an urban waterway can have, but it can be very peaceful, serene.”

On their spring outing, the UMass Lowell students paddle farther up Stony Brook, then squeal and holler as they pass through a nearly pitch-black tunnel that runs under congested Middlesex Road and below a red-brick building. Built in 1897, it was once the storehouse for a mill complex that produced thousands of pounds of worsted yarn per week (for which the brook produced power via a canal). Turning around and traveling back to the pond-like section, everyone looks up and watches a Pan Am Railways freight train rumble by on the old tracks. At such close range, the rush of locomotive power is exhilarating. It also sounds as if the world is ending.

Each summer, thousands of Merrimack Valley children participate in the Greater Lawrence Community Boating program.

Photograph courtesy of Greater Lawrence Community Boating

“Do you swim in the Merrimack?” one young man asks Soleil. The answer is yes—and no. “Much of the time it’s okay,” Soleil answers. “But in the summer, E.coli can form.” Tangible trash is still routinely dumped in the water, although the nonprofit Clean River Project has hauled out more than 100,000 tons of garbage, including 73 cars and more than 8,000 tires, in the last 13 years. But there’s more insidious pollution as well, which is likely the main source of the bacteriathat threaten public health. Parts of the sewer systems in the older, most populated cities along the river are “combined,” meaning rainwater runoff, sewage, and industrial waste are funneled through a single pipe, according to Robert “Rusty” Russell, J.D. ’82, the new executive director of the Merrimack River Watershed Council (MRWC).

Established in the wake of the Federal Water Pollution Control Act Amendments of 1972 (later dubbed the Clean Water Act), MRWC’s mission is to “protect, improve, and conserve” a watershed—the fourth-largest in New England—encompassing 214 communities with 2.5 million residents. “When it rains a lot or you have a big snowmelt, the [combined sewer] system gets overloaded; the treatment plants can’t handle [the volume],” he says. To avoid flooding the treatment plant or nearby pipes, safety valves exist that divert overflow—essentially raw sewage and whatever else gets washed into street drains—directly into the river.

More than 600,000 valley residents drink Merrimack River water. That number is rising with housing and commercial development, especially in southern New Hampshire, Russell notes. Many people don’t realize, he adds, that the Merrimack is the second-largest surface-based source of drinking water in New England after the Quabbin Reservoir. Both are subject to the same laws that theoretically safeguard the water quality, “but with different expectations,” says Russell. “Quabbin must remain pristine; not so the Merrimack. And therein lies the problem”: every developed surface—paved roads and driveways, building foundations, even lawns with packed soil—prevents natural filtration of precipitation. The Environmental Protection Agency cites polluted storm-water run-off as the primary threat facing the Merrimack over the long term.

As it pushes for increased land protection and consistent, coordinated water testing, the MRWC also reaches out to valley residents and visitors, offering more than 15 paddling adventures this year throughout the watershed. A “Trash Patrol” gathers in Nashua on September 2, and there’s an easy-to-moderate river trip in and around Lawrence on September 16 (see the website for other trips, details, and registration.) Also of interest, at the Lowell National Historical Park, the National Park Service runs a 90-minute “Working the Water” boat tour of the Pawtucket Canal that formed part of the mill complex in Lowell.

Dennis Houlihan’s narrated river tours benefit the Clean River Project.

Photograph courtesy of the Clean River Project

Other small groups are also working to improve the river and protect dozens of endangered fish, birds, and other wildlife species across the watershed. New Hampshire contractor Rocky Morrison founded the all-volunteer Clean River Project because he was fed up with seeing the Merrimack trashed. “People just pull over by the side of the river and throw out their TVs and tires because they don’t want to pay the recycling fee,” he says. “In Haverhill, we have a place we call Tire Cove because we found more than 4,000 there alone.”

So far, Morrison’s effort has relied on grants and donations, and people like Dennis Houlihan. He lives on the river in Methuen and runs pontoon-boat tours: each passenger’s $20 goes directly to the project. He takes passengers toward Lawrence, and explains the valley’s industrial history this way: Francis Cabot Lowell, A.B. 1793, “learned about the mills from England, came back to America, and built and opened one in Waltham.” Other entrepreneurial businessmen followed suit, building a mill complex in Lowell, and then more in New Hampshire. Lawrence developed later, in the 1840s, as a more comprehensive planned metropolis, with canals running along both sides of the river to maximize the water power.

The Clean River Project covers only the 15 Massachusetts river communities—about 44 river miles—and has requested municipal funding to hire staff and expand operations. Out on a spring boat tour, Jed Koehler, executive director of the Greater Lawrence Community Boating Program, points out Clean River’s yellow booms bobbing near the shore after his boat clears the foundations and steel girders of the Interstate 93 bridge. “Trash floats down the river like tumbleweeds in the old frontier towns,” he says, applauding the group’s efforts.

A cleaner river is important to his program’s success. It’s the largest public boating program in the Merrimack River Valley, and serves about 2,200 kids a week in the summer. They learn about water safety and how to row, sail, and paddle, and do other day-camp activities; the majority of them are on full scholarships, and 42 percent live in single-female households. “The parent is often working one to three jobs,” says Koehler. “The boathouse is a safe place for their kids to be.”

But anyone can join the program for the season and take out boats, or purchase a day pass. Launching from the Lawrence dock, paddlers can travel about an eighth of a mile downstream, toward the Great Stone Dam, on Bodwell’s Falls, which is on the National Register of Historic Places. When completed in 1848, it was the largest in the world, and is so solidly constructed that it’s never required significant repairs, and is still used for hydroelectric power.

Beyond the dam, and visible from a boat, stands one of the city’s still-ubiquitous red-brick smokestacks. It’s part of the Pacific Mills power plant, according to Jim Beauchesne, the Lawrence Heritage State Park visitor-services supervisor—one of the factories that manufactured fabric for military uniforms for the Civil War through World War II. And there’s the Ayer Clock Tower. Built in 1910, it’s still one of the world’s largest; its four glass faces are only slightly smaller than those on Big Ben. The heritage park’s museum, located in a restored 1840s mill-workers’ boarding house, lays out the city’s history and is well worth a visit.

Yet industry came at a stiff price. Koehler, whose father ran the boathouse during the 1980s and 1990s, says his older board members tell stories of how the river used to “run in colors”—most often vivid green—from vats of dyes dumped by textile firms. “In the 1950s and 60s, the parents would check behind their kids’ ears to see if they’d been swimming in the river,” he explains, “because the kids would wash themselves off in front of a mirror, and never remember to get out the ink or dye behind their ears.”

Today, “the river is cleaner than it used to be,” he says. Steering away from the dam, up the river, he turns into a creek and touts the wildlife: American bald eagles, deer, nesting Canadian geese, dam-building beavers. Turtles lay eggs in the boathouse’s yard. Once the hatchlings have emerged and “are trying to make their way to the water, across the backyard where a hundred kids are about to run around,” he, the staff, and the children gently move them to the shore of the creek. For city kids, Koehler notes, the river is often their primary contact with nature—and plenty of adults, he adds, don’t realize what a respite it offers. “Every evening, the orange sun sets—right there!” he says, pointing upstream from the boathouse. “Right down the center of the river, every night. It’s like Aruba!”

About three-and-a-half miles upriver from the Lawrence boathouse are places to pull in and explore. People walk and picnic on a finger of land called Pine Island, owned by the MRWC. Koehler says the island was once home to a hermit who had a “little shack and a rowboat he used to get back and forth from the shore.” Long before, archaeological evidence shows, the island hosted a Penacook Indian settlement.

The Penacooks once moved freely along the Merrimack River, hunting and fishing. “During the last quarter of the seventeenth century, the Penacook Indians were feared by the residents of Andover,” according to the Andover Village Improvement Society (AVIS) website. “In 1675, the Indians attacked from the north, crossing the river, killing some settlers, and taking others hostage.”

Adjacent to Pine Island is the 131-acre Deer Jump Reservation, owned by AVIS. Its banks run about four feet high, but paddlers can travel up side streams, tie boats to a tree, and scramble ashore. A riverside trail offers easy hiking, and the land is home to hemlock groves and a meadow, an AVIS warden reports, along with fisher cats, otters, wild turkeys, foxes, coyotes, and skunks.

The joy of finding frogs

Photograph courtesy of the Clean River Project

Back in Lowell, Soleil agrees the river offers “a real connection to nature that people are not expecting.” At the end of their trip, the celebrating seniors pull up to the docks and pull out their kayaks. It’s 5:30 p.m. Everyone is a bit wet and wind-blown. The mood is convivial as they thank Soleil for a fun time before bounding away to other evening activities.

“It is what it is,” he says, almost shrugging when pressed to say more about the Merrimack’s “mixed bag.” “My position is that the more people we can get out to experience the river, the more people would care about it, and the better off it would be.”