Although America’s research universities are the envy of the world, our system of baccalaureate education inspires as much hand-wringing as pride. Concerns about the unevenness of undergraduate education have grown with evidence of falling college completion rates and disappointing results in international comparisons of learning. Most prominent have been misgivings about equity and privilege. As income inequality has worsened, elite colleges are being called out as “bastions of privilege.” Critics have asked pointedly whether America’s colleges, rather than serving as a mechanism for equal opportunity, are in fact contributing to more inequality.

Perhaps these equity concerns are overblown. Haven’t admissions criteria become ever more objective and merit-based? Aren’t our college campuses more racially diverse than ever before? Have ever-present disparities simply become salient of late, thanks to the spotlight aimed by egalitarian observers? Or are the critics justified in their jeremiads—perhaps inequalities are growing and the apparent racial diversity simply masks increasing class uniformity among undergraduates?

As a citizen, I am of course aware of the growing economic inequality in American society. As an economist of higher education, I have studied the peculiarities that characterize this industry, its components, and the market for baccalaureate education. Now, I have systematically combined these perspectives to address how undergraduate education has changed as our society itself has changed during the past several decades. I find that interacting market forces have substantially widened the gaps among institutions of higher education and those whom they serve—in ways that pose real challenges for educators, policymakers, and the public at large.

Undergraduate Education as a Market

Though it is rarely referred to in these terms, the market for baccalaureate education is supplied by one of the country’s most consequential industries. Its firms are the roughly 2,000 colleges and universities that offer four-year degrees. It is a quirky industry, to be sure. The product that it sells, sadly for those who wish to measure it, is both amorphous and idiosyncratic. (One reason the output of these firms is so hard to measure is that their customers also supply some of the principal inputs to production: time, attention, and effort.)

Instead of treating all colleges and universities alike—as we normally do, for example, in calculating statistics on educational attainment or the economic value of a college degree—I focused on the differences across colleges. Some of the contrasts that emerge are breathtaking. From the “comprehensive” public universities that once were teachers’ colleges, to tiny religious colleges where students must attend chapel, to our world-famous public and private research universities, the colleges that make up this industry differ in mission, in academic rigor, and in the resources available for learning. The difference between public and private status, in particular, is obviously consequential—fundamentally so.

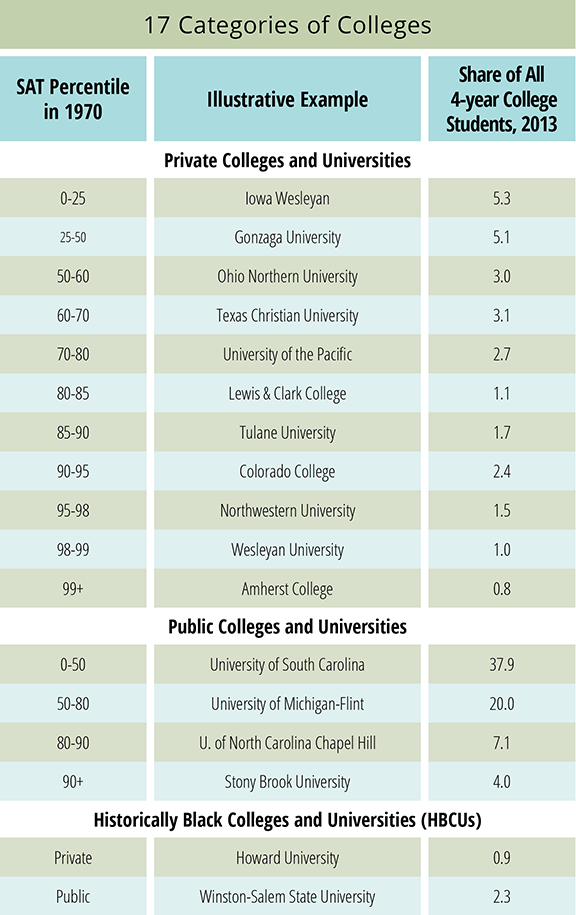

My aim was to document as many of these differences as possible and to see whether the differences have grown or narrowed over time. I divided colleges into more than a dozen contrasting categories, based on the SAT scores of their students around 1970 and whether they were public or private. I also separately analyzed historically black institutions, owing to their distinctive history. Then I examined the institutions in these categories, where possible, across four decades, roughly from 1970 to 2010. (In making comparisons, I used detailed data from UCLA’s Freshman Survey on students who attended one of 188 colleges at three points over this period. I collected other types of information on colleges as well, making sure that each change over time was based on a fixed set of colleges.)

Note: Colleges shown are among the 188 colleges for which data from the Freshman Survey were available for each of three survey waves (1972, 1989-90, and 2008-09).

Source: Clotfelter, Unequal Colleges in the Age of Disparity (Harvard University Press, 2017)

The categories I used are shown above. Because private colleges tend to participate in the Freshman Survey more often than public ones, the data could support a more detailed breakdown among the former institutions than the latter ones, leaving some categories much broader than others. For example, the category containing public institutions whose average student SAT score placed them below the national median in 1970 accounts for nearly 40 percent of all four-year college students. By contrast, the private colleges and universities whose average student SATs were in the top percentile—the marquee selective-admission schools that command so much attention among readers of this magazine and most researchers of higher education—enroll less than 1 percent of all students. It is worth bearing that in mind as we consider where most students are educated, and with what resources.

Scholastic Sorting

To appreciate the magnitude of some of the disparities between colleges, consider the academic credentials of students who attended schools in those two categories: the below-median public colleges (containing, for example, the University of South Carolina and Rhode Island College); and the top-scoring private colleges (containing Amherst and Caltech, among others). In 1972, the cohorts of students enrolling in these two categories of institutions brought markedly different high-school records. Just 7 percent of first-year students in the below-median public colleges reported having high-school grade averages of A or A+, but 39 percent of those at the top-scoring private colleges had that kind of secondary-school record. This 32-percentage point gap is gigantic, though it is the sort of difference that is seldom acknowledged in polite conversation.

Remarkably, this academic gap between the least-selective public and the most-selective private colleges grew even wider over time, as more and more of the best students looked beyond their state or region to the nation’s most selective colleges. By 2008/09, the gap in high-school grades between the South Carolinas and Amhersts had expanded markedly, reaching 43 percentage points.

The students who would enter those most-selective private colleges in 2008/09 had earned their grades by studying even more than their predecessors who had attended those same colleges in 1989/90. While the average reported time spent studying declined for students entering the less-selective public colleges during this period, from 5.0 to 4.6 hours per week, students headed to the most-selective private colleges increased the time they committed to high-school academics, from 10.2 to 11.0 hours per week.

In other ways, too, the academic worlds of the less selective and highly selective colleges have become ever more distinct. For one thing, while less-selective public colleges have increased their offerings of practical, vocational majors, the most-selective private colleges have held fast to the traditional liberal-arts majors. If you want a measure of the academic gulf between these contrasting sets of colleges, consider the outsize footprint of graduates of the two highest-SAT categories of private colleges measured by entering students’ SAT scores. Although these institutions educate less than 2 percent of all four-year college students, their graduates earned 11 percent of all Ph.D.s, made up 39 percent of Harvard Law School students, and won 57 percent of all Rhodes Scholarships.

The Demand Side: Affluent Families and the Admissions Frenzy

Not surprisingly, the demand for admission to these highly selective colleges has increased steadily, buoyed by the rising economic fortunes of families on the top rungs of the income distribution and by the prestige of the colleges themselves. Unlike firms in most markets that encounter rising demand for their product, these colleges chose not to expand their capacity nearly enough to accommodate this demand. The result was progressively stiffer competition for admission—witness the top schools’ annual tally of tens of thousands of applicants and single-digit admission rates.

For thousands of affluent parents, an acceptance letter to one of the colleges in this rarified group ranks as one of life’s most prized trophies. But unlike the markets for almost every other highly desirable commodity, from modern art to exclusive real estate, buyers of higher education cannot secure an admission spot simply by out-bidding other applicants, because these firms employ a decidedly different means of rationing these prized admissions spots. To ration their scarce slots, colleges look to grades, test scores, and other accomplishments.

Affluent parents have been quick to adjust to the heightened emphasis on documentable evidence of merit. Often starting well before high school, children of highly educated parents were playing soccer, field hockey, and lacrosse: sports played at elite colleges. They were volunteering, traveling abroad, and working as unpaid summer interns. Heeding the advice of school and private counselors, they signed up for test-prep courses, often taking the SAT or ACT multiple times. They loaded up on Advanced Placement courses. Many enrolled in private schools that offered academic extras.

As a result, affluent families managed to hold their own in this increasingly meritocratic admissions process. Comparing again the below-median public institutions with the most-selective private colleges, the gap in average family income (in constant 2008/09 dollars), rose from $67,800 in 1972 to $105,000 in 2008/09. During this period, the share of students in the “South Carolina” category whose parents made more than $250,000 (in constant dollars) rose from 3 percent to 7 percent; the share for the “Amherst” category increased from 15 percent to 22 percent.

Confirming this evidence of diverging economic status of students enrolled in the most-selective colleges, consider the share of students who had attended a private secondary school. From 1972 to 2008/09, the share of students at the less-selective public colleges who had attended private high schools held steady at 12 percent, but the share of students entering the most-selective private colleges from private high schools rose from 26 percent to 33 percent.

Just as critics have asserted, therefore, the economic gap between the great mass of students attending the less-selective public institutions and those at the most-selective private colleges has indeed grown. Most of this growing economic disparity does not reflect students from the richest families taking the places of those from lower down the income distribution; rather, it reflects the spectacular increases in income enjoyed by those at the top.

The Inequality Dividend

More potent than these shifts in demand in solidifying the inequality across colleges were marked shifts in supply, all courtesy of broad economic forces—especially the rise in income inequality in American society. Three forces in particular brought about an unexpected financial bonanza for the most selective private colleges:

- First, the unprecedented surge in income enjoyed by those in the top fifth of the income distribution meant that affluent parents—if only their children could be admitted—would not balk at paying the hefty tuition bills charged by selective private colleges.

- Second, the rapid growth in disposable income for those at the very top of the income distribution spurred charitable giving, much of which went to name-brand colleges and universities.

- Third, thanks to a red-hot stock market and other lucrative investing opportunities not available to ordinary individuals, the top university endowments enjoyed fabulous rates of return.

In a textbook example of the Matthew effect (“The rich get richer…”), the already wealthy colleges made out like bandits while colleges of lesser means had to settle for lower returns. To boot, colleges in the public sector faced the additional challenge of state legislatures reining in appropriations.

Endowments at the most-selective colleges and universities skyrocketed. In 1970, the median endowment per student in the two most-selective categories of private colleges was roughly $200,000 (in 2013 dollars). By 2013, those endowments had skyrocketed, respectively, to $520,000 and $1,000,000 per student—a source of revenue virtually nonexistent for less selective private and most public institutions.

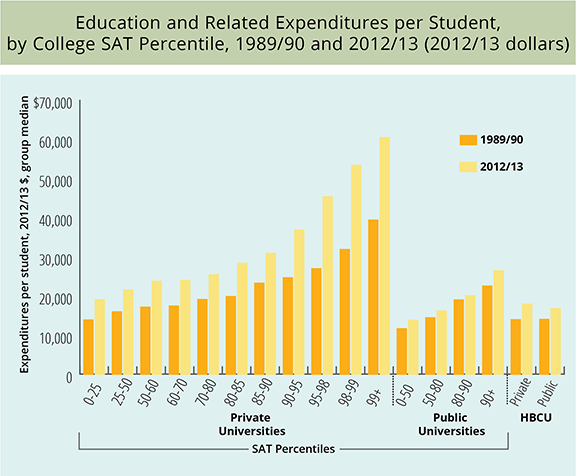

Source: Clotfelter, Unequal Colleges. Based on calculations for 1,114 colleges and universities with data for 1990 and 2013. IPEDS, Delta Cost Project. Medians by group. Education and related expenditures are defined as follows: instruction + student services + (education share) X (academic support + institutional support + operation and maintenance), where the education share = (instruction + student services)/(instruction + student services + research + public service). The median for education and related expenditures was divided by the median of full-time enrollment for each group. The enrollment-weighted average of class medians was $15,762 for 1989/90 and $19,465 for 2012/13.

This breathtaking divergence in economic resources also meant widening differences in spending on academic programs. The chart above summarizes expenditures on education and related activities per student in 1990 and 2013 at more than a thousand colleges and universities. The fruits of the inequality dividend bestowed upon the most-selective private colleges are plain. While inflation-adjusted spending per student at the less-selective public colleges edged up 12 percent, reaching $14,000 in 2013, the comparable figure for the most-selective private colleges jumped by a stunning 50 percent, reaching more than $60,000. (In inflation-adjusted dollar terms, the gap in spending per student increased from about $28,000 to about $47,000 during that period.) These expanding gaps in spending meant bigger disparities in the classroom and across campus, allowing the highly selective private institutions to keep their classes small and hire the most sought-after professors. Meanwhile, students in public institutions and the also-ran private colleges—the places that educate the vast majority of American undergraduates—have had to make do with less.

What It Means

No one meant for this to happen. Forces of demand and supply, not malign motives, produced this growing inequality in the college market. Indeed, the leaders who guide America’s colleges and universities have consistently advocated greater access for low-income students and adequate funding for colleges across the board. But by pursuing prudent policies to protect and advance their own institutions—awarding no-need scholarships, giving admissions preferences to children of alumni, offering applicants the option of early decision, and so on—these leaders have, collectively, added to both the economic forces that have intensified the academic disparities between colleges and the advantages enjoyed by affluent applicants.

American colleges do not need to be as unequal as they are. If some of the largess currently showered on our best colleges were spent instead at institutions of more modest means, we would still have great colleges at the top, but better ones on down the line.

But halting or reversing the slide toward more unequal colleges won’t be easy, even if the desire exists to do something about it. To be sure, Harvard and some of its peer institutions have made efforts, like eliminating loans for their low-income students. Of course, wealthy colleges on their own could certainly do much more—for example, by cutting back on admissions policies favoring the well-to-do or seeking out more low-income applicants—though trustees will tolerate such unilateral actions only so far. More effective would be for colleges to take such actions in unison, but any such concerted efforts would surely prompt antitrust challenges. That leaves government policy, though the appetite in Washington for expanding Pell Grants or easing tax advantages for universities, let alone for changes in taxes or broad social programs that would reduce overall income inequality, is nowhere to be seen.

The founders of America’s colleges, among them philanthropists, religious organizations, and state legislatures, invariably saw in them benign instruments for advancing the greater good. Historian Samuel Eliot Morison tells us that, for its founders, Harvard College represented just one component in a larger set of initiatives, including common schools and printing presses, which were “made by the ruling class of New England and supported by the people at large.”

It should not be surprising, therefore, that for much of our history access to college was largely confined to children of the wealthy and influential. But, as Christopher Jencks and David Riesman wrote nearly 50 years ago in The Academic Revolution, it would be unwise to allow colleges simply to replicate elites from one generation to the next, without allowing clever and energetic young persons of modest means to ascend into positions of influence. To their credit, America’s most selective colleges have become steadily more meritocratic in their admissions criteria, but this has not been enough to overcome the forces of inequality.

In assessing the changes in the market for college, we would do well to keep in mind the potential for good that colleges as a whole have to serve the country by, as Thomas Jefferson wrote, training future leaders who would be “called to that charge without regard to wealth, birth, or other accidental condition or circumstance.” This will be a continuing challenge for America’s market for colleges.