What goes on in the minds of babies? A lot, it turns out: long gone are the days when psychologists believed infants couldn’t use abstract thought. Recent research from the lab of Elizabeth Spelke, Berkman professor of psychology, suggests that babies can understand things about social behavior, preferences—even about people’s objectives and values. According to a new paper in Science coauthored by psychology Ph.D. candidate Shari Liu, Spelke, and colleagues at MIT, infants seem to infer how much people value different goals based on how hard adults are willing to work to attain them. The research sheds light not just on the developing infant mind, but on the fundamental process that allows humans to learn and reason.

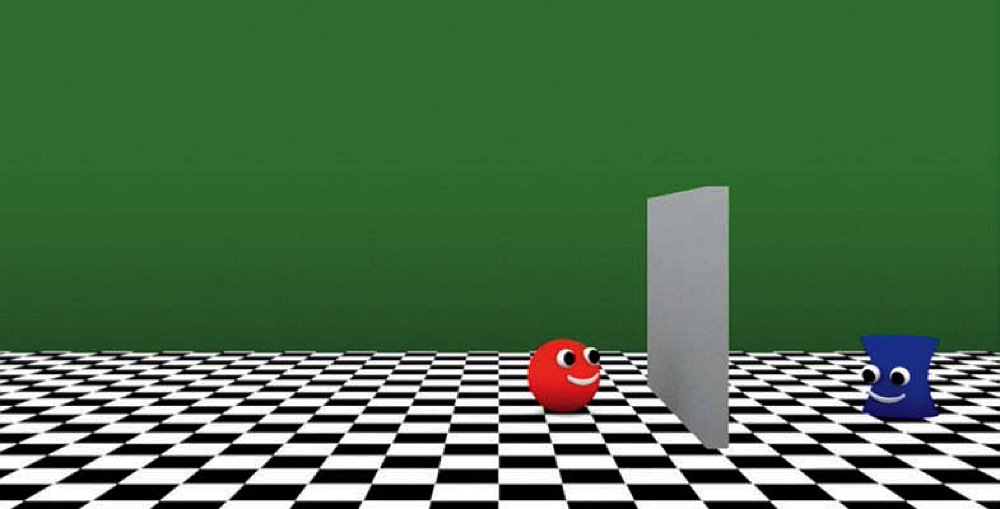

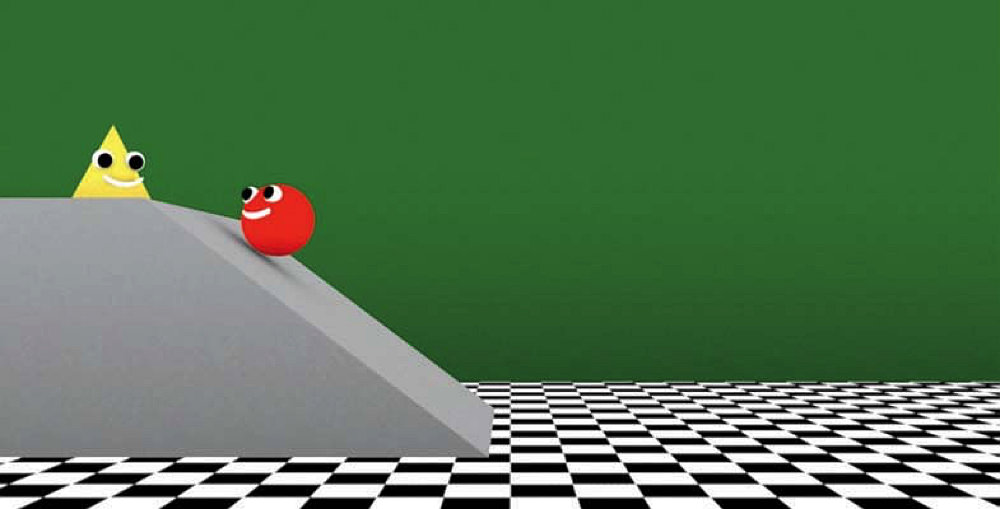

The study relied on a set of three cleverly designed experiments that use the length of time babies spend looking at an object to make inferences about their cognition. Ten-month-old babies were shown a series of animated videos where the main character—a smiley, bright-red sphere—must move through physical barriers of varying difficulty to reach two different objects. The character eyes each object up and down, making a cooing “mmm” noise of acknowledgement. In the first experiment, the character must jump over walls of different heights to reach the objects; in the second, it must climb hills of different levels of steepness; and in the third, jump over trenches. In some trials, the character glances at the object that’s hardest to reach but refuses to visit it because of the perceived barrier.

One of the experiments shows an animated figure jumps over a trench

Video courtesy of S Liu et. al, Science (2017)

Then the babies were shown a new scene in which the character is faced with a choice. Standing equidistant between two objects it had visited previously—a yellow triangle and a blue square, for example—the character must choose which one to approach. When the character chose the object that had previously required less effort to reach, the babies looked at the screen longer. The team says this shows babies were surprised by choices of objects that had previously required less effort to attain, and further argues that this suggests infants have an innate understanding of cost and value: they expect that goals people work harder to reach must be valued more, and expect actors to choose the highly valued, hardest to reach reward. “The most parsimonious interpretation of the findings,” Spelke says, “is that babies are understanding the events in all three experiments in accord with the same abstract variables of cost and value, and they’re using the different physics of the situations to infer the different costs of the actions.”

“Of course, that’s a very simple inference,” she continues. “It’s a basic tenet of utility theory, and yet it depends on two highly abstract variables: cost and value. We now have evidence infants are understanding the actions they’re seeing in fundamentally the same kind of way.” The key to the experiments was designing scenarios that were identical in every way except in the size of the barrier between the character and his goal objects: “What we tried to do in this study was set up a situation where if the babies were just interested in physical actions, and not so much in abstract variables that could underlie whole patterns of motivated behavior, they wouldn’t know what to make of the events they were seeing.”

In videos screened for babies in the lab of Elizabeth Spelke, the red spherical character must jump over a wall (top) or climb a hill (bottom) to reach its goal.

Video stills courtesy of S. Liu et al., Science (2017)

“Preferential looking” or “looking-time” studies were developed in the 1950s, as a way of asking basic questions about how the world looks to babies: can they see color, patterns, and depth? “You could show that blue and green look different to babies by presenting something blue again and again, until the looking time went down, and then show them an alteration, like green, and then you would see looking time going up,” Spelke explains. “That was the first evidence that babies would attend to change.”

In the intervening decades, looking-time studies have expanded beyond visual acuity to more difficult questions about babies’ capacities for abstract thinking. “These are the basic, building-block methods that we and many people have gone on to use to ask, not ‘What does the world look like to infants?’ but, ‘What they do understand about the world?’ ” Spelke explains. In the 1980s and ’90s, her experimental work showed that babies look longer at objects that seem to defy physical laws by, for example, appearing to move through an obstruction. That might sound trivial to an adult mind—but it suggests that infants aren’t blank slates born without a mental architecture for understanding the world—in fact, they’re attentive learners. “It may be that the reason a baby looks longer when an object seems to go through a wall or when someone chooses a reward that is less valuable,” Spelke says, “is not that they’re thinking, ‘Something’s wrong here’—but rather they’re thinking, ‘I must have missed something. I didn’t expect that object to go through a wall, so maybe I should pay more attention and figure out why that happened.’”

An immediate implication of the study and others like it, Spelke says, is that infants’ capacity for learning depends on their ability to grasp abstract relationships: “Infants have an enormous amount to learn about the world, about agents, how they behave, what they want, what they care about. What makes that possible? I think it’s possible because they’re able to understand patterns of activity in terms of variables like cost and reward.” More ambitiously, infant research may also help bring to light building blocks of human cognition that cut across human societies. “Even though infants seem to be utterly different from us—with this huge gap between what we understand about the world and what they understand—there are nevertheless basic, fundamental relationships that we may apply to the world in the same way that they do. It may be these relationships that ultimately are going to help us understand” why humans are “such incredibly flexible, prolific, creative learners.”