It is not intuitive that a case needs to be made for “Reason, Science, Humanism, and Progress,” stable values that have long defined our modernity. And most expect any attack on those values to come from the far right: from foes of progressivism, from anti-science religious movements, from closed minds. Yet Steven Pinker argues there is a second, more profound assault on the Enlightenment’s legacy of progress, coming from within intellectual and artistic spheres: a crisis of confidence, as progress’s supporters see so many disasters, setbacks, emergencies, new wars re-opening old wounds, new structures replicating old iniquities, new destructive side-effects of progress’s best intentions. Pessimism doubts whether progress will deliver on its promise of a better tomorrow, while cynicism questions whether today is truly better than our ancestors’ yesterdays. Do science and technology genuinely make our lives better, or fill them with new problems as we are dragged, like Charlie Chaplin, by the unstoppable machine of Modern Times?

These questions are not new. Jean-Jacques Rousseau asked them in Enlightenment Paris, the Romantic movement did the same in the chilling wake of the French Revolution, and Sigmund Freud asked them when reflecting on World War I. But especially in the last few years, they are being asked again, and in new ways.

So Harvard’s Johnstone Family professor of psychology sat down to answer them, to defend the thesis that we have made progress, that our present is better than our past, and that our future—through our efforts—can surpass this present. As Pinker puts it: “The Enlightenment principle that we can apply reason and sympathy to enhance human flourishing may seem obvious, trite, old-fashioned. I wrote this book because I have come to realize it is not.”

Pinker’s volume moves systematically through various metrics that reflect progress, charting improvements across the last half-century-plus in areas from racism, sexism, homophobia, and bullying, to car accidents, oil spills, poverty, leisure, female empowerment, and so on. Unexpected among his charts of changes is one suggesting that atheism is increasing and religiosity decreasing in the United States. Charts are easy to niggle at: a chart of declining war deaths per annum beginning in 1945 might look very different had it started in 1600. But if one reads them fairly, the majority of the data and analyses Pinker provides are convincing, painting a repetitive and unrelenting portrait of improvement.

Repetitive and unrelenting are rarely positive qualities in a book, but here they genuinely are, because the case Pinker seeks to make is at once so basic and so difficult that a firehose of evidence may be needed—optimism is a hard sell in this historical moment. Pinker borrows David Deutsch’s characterization of optimism as “the theory that all failures—all evils—are due to insufficient knowledge....” Acknowledging nineteenth-century Romanticism as the first major counter-Enlightenment movement, Pinker credits the surge in such sentiments since the 1960s to several factors. He points to certain religious trends, because a focus on the afterlife can be in tension with the project of improving this world, or caring deeply about it. He points to nationalism and other movements that subordinate goods of the individual or even goods of all to the goods of a particular group. He points to what he calls neo-Romantic forms of environmentalism, not all environmentalisms but specifically those that subordinate the human species to the ecosystem and seek a green future, not through technological advances, but through renouncing current technology and ways of living. He also points to a broader fascination with narratives of decline, a declinism or apocalypticism that foresees the end of our era either through nuclear war or some other technological annihilation, or through the hollowing and degeneracy of modern society.

To these decades-old causes, one may add the fact that humankind’s flaws have never been so visible as in the twenty-first century. We face enormous challenges on many fronts: health, poverty, equality, ecology, justice. These are not new problems, but our failures are more visible than ever through the digital media’s ceaseless and accelerating torrent of grim news and fervent calls to action, which have pushed many to emotional exhaustion. Within the last two years, though not before, numerous students have commented in my classroom that sexism/racism/inequality “is worse today than it’s ever been.” The historian’s answer, “No, it used to be much worse, let me tell you about life before 1950...,” can be disheartening, especially when students’ rage and pain are justified and real. In such situations, Pinker’s vast supply of clear, methodical data may be a better tool to reignite hope than my painful anecdotes of pre-modern life.

After the data deluge, the book concludes with three chapters defending the three major human tools Pinker advocates: reason, science, and humanism. In the section on reason, he names political prejudice and polarization as major new threats to the exercise of reason, including what he calls the politicized “liberal tilt” of academia. Arguing against the assertion that humans are fundamentally not rational, he points out, rightly, that Enlightenment thinkers claimed only that we are capable of exercising reason, not that we always do, and that exercising reason is useful and beneficial. Here (and in the chapters on equal rights and the future of progress) Pinker offers his most substantial examination of Trumpism and related issues, but here, too, he is positive, urging advocates of rationality to resist the cynicism of calling this a post-truth world. Facts and logic have a cumulative persuasive force, he argues. Stories that expose falsehoods have proven excellent clickbait, he observes, and are on the rise in number and popularity—and editors have spotted this trend.

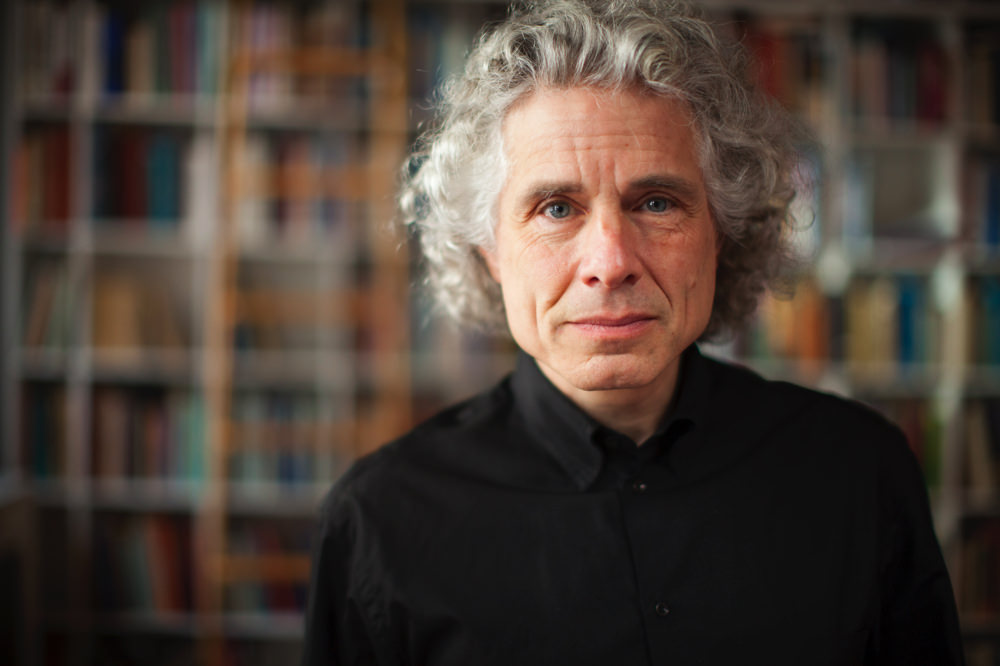

Steven Pinker

Photograph by Stephanie Mitchell/Havard Public Communications and Affairs

Pinker’s celebration of science is no holds barred: he calls it an achievement surpassing the masterworks of art, music, and literature, a source of sublime beauty, health, wealth, and freedom. His survey of anti-science rhetoric focuses on movements that try to limit science to the material and technological realms, and regard with suspicion scientific attempts to inform ethics, values, or culture. He is particularly critical of arguments blaming science for social evils, stressing the need to distinguish between science itself and moments when science has been twisted to bad ends, be those social Darwinism or gender inequality. His attack on the value of bringing gender and social-justice lenses into science studies is problematic, but he correctly suggests that social-justice movements can benefit by approaching science as a potential ally rather than presuming it an enemy.

But science can easily be twisted to serve injustice or destruction. Pinker’s solution to this risk is humanism. It can prevent science from being an enemy of progress and happiness, he argues, by keeping science’s power to do anything from actually doing terrible things.

Humanism has many definitions, but Pinker’s is what we may call modern secular humanism, which he defines as “the goal of maximizing human flourishing—life, health, happiness, freedom, knowledge, love, richness of experience,” adding that it “doesn’t exclude the flourishing of animals” and that it “promotes a non-supernatural basis for meaning and ethics: good without God.” He associates this humanism with the earthly, world-improving values of the American Declaration of Independence, and with Enlightenment and post-Enlightenment ideas of human rights. Pinker reviews what he sees as humanism’s intellectual adversaries, such as those who caricature it as cold utilitarianism, those who suggest that humans have an innate need for spiritual beliefs, and the classic accusation, ubiquitous in the Renaissance and Enlightenment, that there cannot be good or virtue without God. For some readers, it will be frustrating that 350 pages of useful and cheering data, the majority of which one could call faith-neutral, culminate in the declaration that only triumphant atheism can ensure that scientific progress will help instead of harm. But Pinker’s secular humanism is less militant than that of many contemporary atheist voices; he focuses on the benefits of caring about the earthly world, rather than on condemning religion. His conclusion, that progress simply requires us to value life over death, health over sickness, abundance over want, freedom over coercion, happiness over suffering, and knowledge over superstition, is one numerous theisms can and have embraced.

Pinker briefly reviews efforts to value other factors—love, passions, feeling—above reason, but declares such efforts self-defeating: as soon as they attempt to justify themselves, the very act of providing reasoned arguments for their beliefs admits that reasoned arguments are the strongest grounds for belief. Yet, as I reflect on this argument, I am reminded how science, during a critical moment in its history, was self-defeating in much the same way.

Progress in the modern sense, as an intentional and human-driven process, was first fully articulated by Francis Bacon early in the seventeenth century, when he suggested that a collaborative community of empirical inquiry would uncover useful truths that would radically transform human civilization and make each generation’s experience incrementally better than that of the generation before. This was not the easy sell it seems, since Bacon had no evidence that this unprecedented project could wield such power—and even if he had found evidence, one can’t use reasoned evidence to prove that reasoned evidence can prove things. New discoveries were frequent—the moons of Jupiter, the magnification of insects, the circulation of the blood—but practical benefits were slow in coming.

As Harvard professor of history James Hankins once put it, it was the nineteenth century that finally paid Bacon’s IOU: if his peers poured fortunes and lifetimes into science, they would receive in return wealth and technologies that would improve the human condition. As Bacon puts it in his New Atlantis, knowledge of the causes and secret motions of things would extend the bounds of human empire to the achievement of all things possible. Yet Bacon did succeed in awakening a groundswell of enthusiasm (and funding) for reason and science, through an argument that often surprises my students: he appealed to the personality of God, arguing that a good Maker would not send humans out into the wilderness without the means to achieve the desires implanted in us. Thus, because reason is God’s unique gift to humankind, it must be capable of all we desire.

From time to time, particularly in the aftermath of the French Revolution, champions of secularized science have been embarrassed by this comment from Bacon—worrying what would happen if their atheist followers realized that science, at its inception, had no secular evidence to support its own faith in the power of evidence. One cannot help but wonder how Bacon’s world would have responded to an avalanche of data similar to what Pinker offers. Bacon himself might weep for joy to see his project’s future so affirmed. But with Pinker’s entire book in hand, Bacon would also have felt the tension between two arguments running through it: the inclusive argument that reason, science, humanism, and progress have made our present better than our past, and can make our future better still; and the less inclusive argument, however eloquently and intelligently presented, that the humane and empathetic humanism capable of turning our powers to good and away from evil must be secular.

Pinker is no more successful than Bacon at justifying science and reason without a recursive appeal to science and reason. Yet for those already confident in the persuasive force of evidence, it would be hard to imagine a more encouraging defense than Pinker’s of the reality and possibilities of progress.