Highlights for fiscal 2018:

•The endowment’s value was $39.2 billion as of this past June 30, the end of fiscal year 2018—an increase of $2.1 billion (5.7 percent) from $37.1 billion a year earlier. The gains in the year just ended bring the value of the endowment above the level of $37.6 billion realized at the end of fiscal 2015: the first time its nominal peak value had exceeded the $36.9 billion realized in fiscal 2008, immediately before the financial crisis and recession. So, for two years running, Harvard Management Company (HMC)—with considerable help from philanthropy during the capital campaign (see below)—has reported an endowment value that exceeds the fiscal 2008 total. (None of these figures are adjusted for inflation, which has reduced the purchasing power of the endowment by several billion dollars during the past decade.)

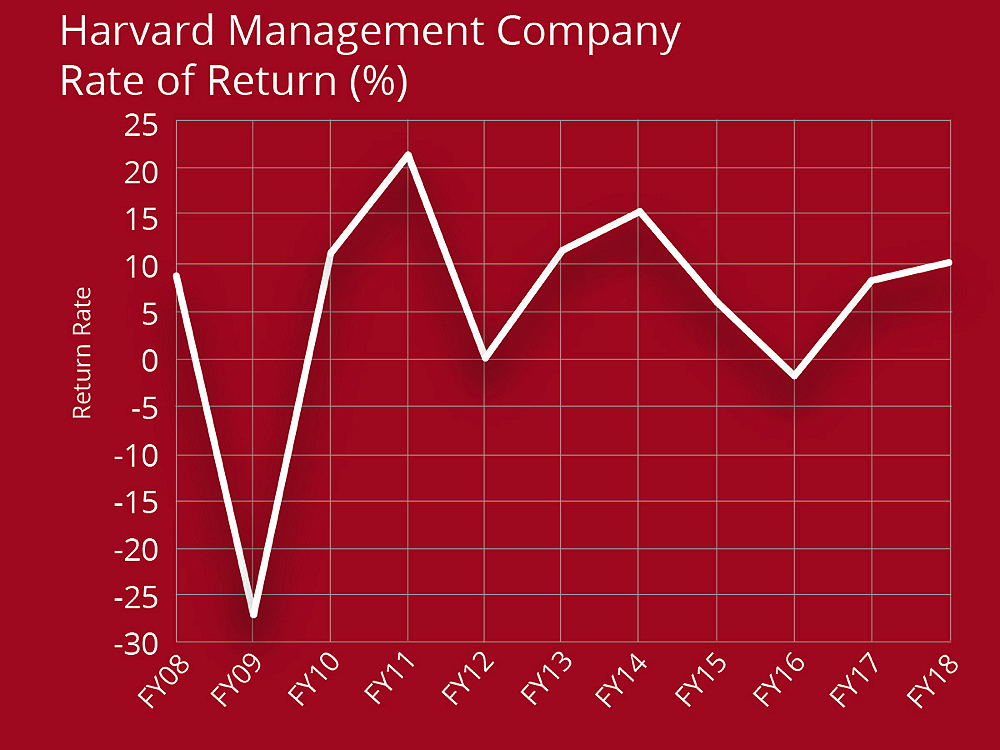

•In a year of improved investment returns generally, HMC recorded a 10.0 percent return on endowment assets during fiscal 2018: up from the 8.1 percent rate of return recorded during the prior year, and the negative 2.0 percent return in fiscal 2016. The return figures take investment expenses and fees into account. But because HMC did not detail internal restructuring costs (severance, for example) incurred during fiscal 2017, or the magnitude of asset impairments and revaluations recorded then (or actual losses or gains realized on sales), it is unknown whether the comparatively higher returns reported for 2018 in part reflect prior one-time factors.

HMC’s most recent investment results trail those of some other institutions that have reported to date (see below). When others report, it appears likely that HMC’s results for the year will remain 2 to 3 percentage points lower than the returns achieved by its closest peers. When applied to an asset pool the size of the Harvard endowment, that margin translates into at least hundreds of millions of dollars less in investment gains for the University during fiscal 2018.

•Consistent with the practice established last year, when N.P. Narvekar first reported HMC’s results (he arrived as chief executive officer in late 2016), the management company has slimmed down its reporting—to a startling degree. Last year, it declined to provide results by class or segment (reflecting the new approach of managing the portfolio on a more holistic basis, rather than the past practice of separating and weighting investments by types of assets). Nor did it share its performance benchmarks, or publish multiyear, annualized rates of return. (As of fiscal 2016, HMC’s annualized five- and 10-year rates of return were reported as 5.9 percent and 5.7 percent, respectively: well below the long-term goal of an annualized 8 percent return—and the basic reason why the organization and its investments are being remade under Narvekar).

This year, he dispensed with the annual letter altogether, instead issuing a four-sentence note. The first conveyed the rate of return and June 30 endowment value, and the rest, in its entirety, read:

As is well known, HMC, as an organization, and the endowment portfolio are still in the early stages of a multi-year transition, with much work ahead. Thanks to the exceptional team we have at HMC, we are confident in the direction of the organization and the long-term prospects for the endowment.

For those interested, further details of our organizational progress and investment returns will be available in the University’s financial report, next month.

Although this has the logistical virtue of not duplicating reports (Harvard’s financial report for fiscal 2018 will become available in late October), it means that HMC’s status and results—during a period of wholesale transformation of managing the endowment, the outcome of which is critical to the University’s financial health—are, for now, essentially opaque.

As always, the change in endowment value reflects three intersecting factors:

- the investment return (positive this year);

- the regular distribution of funds—a withdrawal from the endowment, to support Harvard’s operations—and possibly other one-time distributions, so-called decapitalizations; and

- the gifts added to the endowment, as pledges are fulfilled and proceeds received—the fruits of The Harvard Campaign, also concluded last June 30.

Results in Fiscal 2018

HMC, which invests the University’s endowment and other financial assets, announced today that during fiscal 2018, the endowment’s value increased 5.7 percent, to the reported $39.2 billion; during the prior year, its value had appreciated 3.9 percent, to $37.1 billion (a rebound from the 5.1 percent decrease in value during fiscal 2016 and 3.3 percent gain during fiscal 2015).

In absolute terms, the endowment’s value increased $2.1 billion during the year just ended. That reflects the intersection of:

Appreciation. HMC’s money managers—increasingly, external investment firms—realized an aggregate 10.0 percent investment return (realized and unrealized; after all expenses), producing an increase in value of perhaps $3.5 billion. (Transfers and timing differences—when funds are received and disbursed—figure in the final rate-of-return calculation and reported endowment value; exact figures await publication of Harvard’s annual report.)

Distributions. The reason Harvard has an endowment is to provide a permanent source of capital, earnings from which can be distributed to pay for the University’s operations; such distributions of course reduce the endowment’s value. In fiscal 2017, those distributions accounted for 36 percent of the revenue used to run the place: nearly $1.8 billion—by far the largest single source of revenue. (Investment income earned on other University funds and also applied to support the operating budget totaled about $200 million, and a bit more than $50 million of endowment appreciation was distributed in the form of “decapitalizations.”)

A precise figure for the fiscal 2018 distribution again awaits the University financial report, but it is reasonable to estimate that it grew somewhat from the $1.8 billion in fiscal 2017 (which was up about 4 percent from approximately $1.7 billion in the year-earlier period). In order to maintain the endowment’s purchasing power and to smooth the year-to-year operating effects of sharp changes in investment returns, the Corporation uses a formula to set future distributions, so deans can set their budgets rationally (see “How the Endowment Distribution Is Set”).

Given the 5.1 percent decline in the endowment’s value during fiscal 2016 (reflecting the negative investment return and the funds distributed that year), deans were instructed to assume a level distribution (zero increase per each unit of endowment owned) in their fiscal 2018 budgets. In fact, to the extent that their schools have received endowment gifts or transferred funds into their endowment accounts (thus accumulating more units of endowed funds), they may have received more in absolute dollars distributed from the endowment, even as the rate of distribution on each unit owned was held steady. Accordingly, an appropriate back-of-the envelope estimate might call for a 2 percent to 3 percent increase in funds distributed, or perhaps $1.9 billion in fiscal 2018, in light of gifts flowing in from the campaign (see below).

During the current decade, a pattern of mixed investment returns and relatively generous endowment distributions (the principal factors determining the endowment’s year-end value) has resulted in the following outcomes (fiscal year, rate of investment return, year-end value after all distributions and gifts):

- Fiscal 2017: 8.1 percent (year-end value $37.1 billion)

- Fiscal 2016: (2.0) percent (year-end value $35.7 billion)

- Fiscal 2015: 5.8 percent (year-end value $37.6 billion)

- Fiscal 2014: 15.4 percent (year-end value $36.4 billion)

- Fiscal 2013: 11.3 percent (year-end value $32.7 billion)

- Fiscal 2012: (0.05) percent (year-end value $30.7 billion)

- Fiscal 2011: 21.4 percent (year-end value $32 billion)

- Fiscal 2010: 11.0 percent (year-end value $27.4 billion)

Gifts. The value of the endowment is augmented by capital gifts received during the year and fulfillment of pledges of gifts for the endowment made earlier. Given the June 30 conclusion of The Harvard Campaign—and the announcement that it yielded $9.62 billion in support for Harvard, some $4 billion of which is designated for the endowment—this effect should be pronounced now. In fiscal 2017, Harvard logged $550 million in gifts for endowment, up from $491 million the prior year. With nearly $1.1 billion of endowment pledges receivable as of June 30, 2017, and a bang-up final year of capital-campaign fundraising now booked, it may be reasonable to estimate that gifts for endowment held steady at around $500 million during fiscal 2018 (pending the actual figure in the University financial report).

Thus, the rough calculation would be:

- $37.1 billion beginning value as of July 1, 2017,

- plus $3.5 billion (fiscal 2018 investment gains),

- minus $1.9 billion in operating distributions for the University budget (with no estimate made for decapitalizations),

- plus perhaps $0.50 billion in gifts for endowment received and new pledges,

- equals the endowment’s reported $39.2-billion value as of this past June 30.

The Market Environment and Peer Comparisons

The year ended June 30 was a relatively favorable one for investors. Broad indexes of U.S. stocks appreciated 12 percent to 14 percent; international equities gained about half that much. Bond markets were flat to modestly down, reflecting rising interest rates (the flip side of the economic growth that propelled stocks higher). Of course large endowments, like Harvard’s, invest in a very diverse mix of assets, so returns on private equity (see Virginia’s report, below), real estate, and other investments affect results significantly.

The Wilshire Trust Universe Comparison Service, prepared by Wilshire Analytics, reported median annual returns for large foundations and endowments of 10 percent. Its definition of “large” asset pools begins at $500 million, implying a cohort with very different needs and portfolios than those managed by HMC and the University’s largest peer institutions, but this is still a useful proxy for endowment investments.

Among schools that have reported results (thus far excluding Yale, Stanford, and Princeton, whose portfolios are HMC’s nearest cousins in size and asset mix):

[Updated October 1, 2018, 1:15 p.m.: Yale today reported a 12.3 percent investment return and 8.1 percent growth in the value of its endowment, from $27.2 billon to $29.4 billion; it is in the quiet phase of a major capital campaign, so it may be accumulating early gifts for its endowment.]

[Updated October 4, 2018, 8:30 a.m.: Stanford today reported an 11.3 percent investment return and 6.9 percent growth in the value of its endowment, from $24.8 billion to $26.5 billion as of August 31, the end of its fiscal year.]

[Updated October 9, 2018, 8:40 a.m.: Princeton reported a 14.2 percent investment return and 8.8 percent growth in the value of its endowment, from $23.8 billion to $25.9 billion as of June 30.]

- MIT, a perennially strong performer, had a 13.5 percent return, increasing its endowment to $16.4 billion—up 10.6 percent from fiscal 2017.

- Dartmouth earned a 12.2 percent return on its smaller endowment, increasing its value to $5.5 billion—up 10.9 percent from the prior year. (Its annualized five- and 10-year rates of return are 10.6 percent and 7.6 percent, respectively.)

- The University of Virginia, another long-term strong performer, booked an 11.4 percent return on its $9.5-billion long-term pool, led by 22.9 percent and 13.8 percent returns on private and public equities, respectively. (Its five- and 10-year annualized rates of return are now 9.6 percent and 7.9 percent.)

- Notre Dame enjoyed a 12.2 percent investment return, resulting in a year-end endowment value of $13.1 billion—up 11 percent.

- And the University of Texas Investment Management Company, which oversees assets for UT and Texas A&M, reported an 11.3 percent return on a $30-billion-plus portfolio.

As Narvekar has noted, each institution’s finances, needs, and risk profile are unique. For example: Stanford, the University of Pennsylvania, and Yale consolidate their academic hospitals’ results; Harvard does not. Harvard operates much larger graduate and professional schools than Princeton or Yale, and accordingly supports much greater investment in costly infrastructure for scientific research. So HMC’s strategies, assets, and return goals should be tailored to the University’s unique requirements: that, and performance through the peaks and troughs of investment cycles, rather than an annual performance race, are of the greatest importance to Harvard’s long-term academic standing.

That said, comparable research institutions compete with Harvard for talent and resources. Over time, the University surely wants its long-term investment returns on the endowment—and therefore its potential for distributions to support teaching and research—to be fully competitive, too.

The Year in Perspective

As previously reported, following a protracted period of underperformance, Narvekar assumed the leadership of HMC with a mandate for change—and promptly began a sweeping overhaul of the organization and its personnel, investment disciplines and processes, and much of the portfolio. Many endowment assets, by design, are long-term, relatively illiquid holdings, and relationships with external asset managers are developed over time. Accordingly, in reporting results last year, just several months into his tenure, he forecast a five-year transition process for HMC to realize the University’s investment goals on a sustained basis.

One year’s results provide, at best, only limited insight into the long-term outcome Narvekar and the HMC board seek. For perspective, it is worth noting that a seven-year capital campaign, the largest in higher-education history, attracted $4 billion in gifts to bolster the endowment—about the same sum HMC generates in returns in a single year of median investment performance. Narvekar’s succinct fiscal 2018 message provides no insights into how that critical transition is proceeding, or how far along he thinks HMC is in remaking itself.

The Corporation’s fiduciary decision to restrain the distribution during the year just ended has the practical effect of making the value of the endowment grow faster: incremental earnings are retained, not released to pay for faculty salaries, teaching, research, and so on. Combined with the possibility that one-time costs may have reduced the fiscal 2017 rate of return (if they were not offset by realized gains on the sale of assets), as discussed above, the two years represent something of a transitional period in Harvard’s spending and investments and may not, as the saying goes, be a guarantee of future results. Together, such factors would make the recent growth in the value of the endowment—or as deans might see it, future spending power—appear relatively robust compared to prior years, even as HMC’s investment returns lag behind peer institutions’ results during the restructuring and reorientation of its portfolio.

The Corporation has indicated that it will continue to exercise restraint in fiscal year 2019, now under way, and the two years thereafter. Given the relatively weak returns in prior years, the extensive and time-consuming HMC restructuring, an uncertain economic and political environment, and the arrival of a new Harvard president who will want to shape his own agenda, the Corporation adopted a “collar”: it has told schools to plan for per-unit endowment distributions to rise between 2.5 percent and 4.5 percent annually, starting with 2.5 percent this year. Whatever the operating effects, holding the distribution level in fiscal 2018 and operating within the collar thereafter should provide some breathing room for HMC as it remakes the portfolio, and could, with favorable returns, help restore some of the endowment value lost during prior periods of mixed returns and more generous distributions.