“We are gathering experience,” Bauhaus workshop master Josef Albers told his students, as if art education were similar to apple-picking. “It is not an attempt to fill museums.” Between 1923 and 1933, Albers taught the Bauhaus’s introductory course, which tried to scoop the gunk of aesthetic tradition and creative convention out of students’ heads. When Johannes Itten designed the course in 1920, he and his colleagues were trying to find a home for art in a freshly modern world. For them, this involved excavating primordial geometry out of unruly matter, breaking the rainbow into bite-sized chunks, learning to translate every crumb of human experience into an acutely expressive line. The Bauhaus (literally, “building house”) worshiped form at a moment when abstraction in art was shiny and new and still felt dangerous. The school wanted to nurture a dialogue among media that its members believed had become desperately isolated from each other in society—to bring weaving and painting and metalwork together as tools to interrogate the mystery of sensation.

Museums were filled, nonetheless. The exhibition “The Bauhaus and Harvard,” which opened at the Harvard Art Museums in February, marks the centennial of the school, which was born in Weimar in 1919 when Walter Gropius retrofitted the Grand-Ducal Saxon School of Arts and Crafts into an incubator for modernist teachings. Gropius, a pioneer of modernist architecture, would later chair Harvard’s architecture department for decades. The current exhibition, a stateside component of the extensive global fête for this hugely influential movement, is the University’s first major display of its Bauhaus holdings since 1971, even though they make up three-quarters of the Busch-Reisinger’s collection. From among those 50,000 objects, the Busch-Reisinger’s research curator, Laura Muir, and Engelhorn curatorial fellow, Melissa Venator, had to whittle their list down to 200.

“We have really taken our lead from this collection and the stories it can tell us,” said Lynette Roth, Daimler curator of the Busch-Reisinger, during a preview of the exhibition. The show, therefore, focuses on the first period of the Bauhaus under Gropius, and on the afterlife of Bauhaus pedagogy and principles in the United States. It includes paintings and weaving and chairs and teapots, but also correspondence, teaching notes and class exercises, little paper constructions and color wheels. These teaching materials, from both Bauhaus classes and their U.S. progeny, have spent the past decades in off-site storage, but finally have the chance to emerge into the public eye. “It’s amazing that they’ve survived so long,” Roth said. “These objects had really interesting lives.”

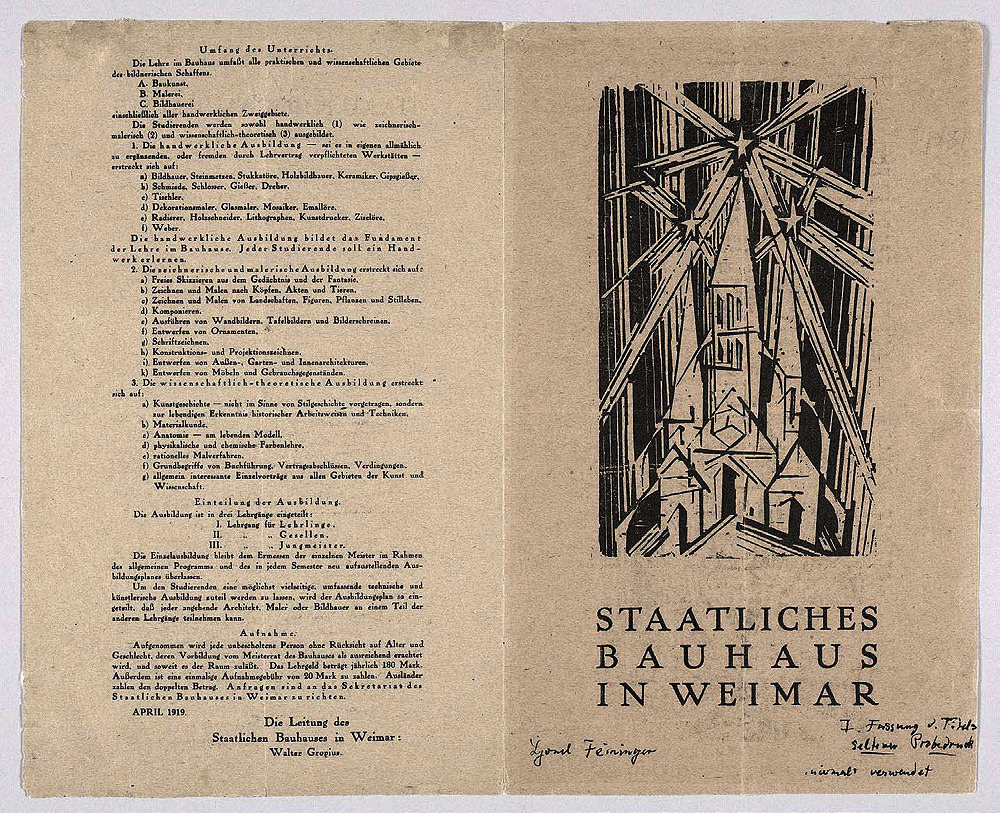

Lyonel Feininger’s Preliminary design for the Program of the State Bauhaus in Weimar: the crystal symbol of a new faith (1919)

Image courtesy of the Harvard Art Museums and Busch-Reisinger Museum, ©President and Fellows of Harvard College

The Bauhaus probably brings to mind loud reds and yellows and blues, charismatic geometry, the smooth wood of modernist furniture. But the piece at the entrance to the exhibition is small and unenticing: withered beige paper with several German words in black block letters and a rough linear representation of an angular cathedral under a sky of black and white stars. This is the preliminary design of the first document produced by the Bauhaus: its Manifesto, an eternally controversial treatise produced in 1919, the year Gropius founded the school. It calls for architects and artists and artisans to gather as partners in the creation of a new society, to “rescue” the arts from isolation by dismantling the class division between modernist art and preindustrial craft. The Bauhaus wanted utopia: the arts, unified, would create a future that would “one day rise toward heaven from the hands of a million workers like the crystal symbol of a new faith.” (The pamphlet’s quasi-religious leftism had to be toned down before the text could be shared with a more conservative U.S. audience at the Museum of Modern Art 20 years later.)

The Manifesto was distributed throughout Weimar at a time when pamphlets served the twenty-first century function of Twitter, a way to attract early students. This version is unique: it bears the preliminary cover design by Lyonel Feininger, master of the school’s printmaking workshop. The cover was a woodcut—a traditional and labor-intensive craft technique, through which Feininger embodied the ideological aims Gropius proclaimed within. It drew on a large body of sketches Feininger had made of German churches during World War I. The image of the fractured, faceted church might represent the breaking up of a national aesthetic weighing down modernist aspirations: the Cathedral of Modernism as a sanctuary in the fight against the cluttered Victorian aesthetic of pre-war Germany, made from the ghosts of that country’s churches. It has traveled a long way and lived many lives in the century since its publication.

The exhibition highlights a relationship between two communities that were first and foremost places of learning—one more fun than the other.

In 1933, the Nazis forced the Bauhaus to close. Classes were relegated to the masters’ living rooms, before petering out as the political situation grew worse. Members of the American art elite began to talk about bringing the school’s faculty to the United States. Feininger arrived in 1936 after his work was included (alongside that of many Bauhaus faculty members) in the Nazis’ Degenerate Art exhibition (see “Making Modernity,” November-December 2015, page 45). Joseph Hudnut, the new dean of the Graduate School of Design, coaxed Gropius to Cambridge to chair the department of architecture. Students and colleagues followed, and Harvard quickly became one nucleus of a growing network of Bauhaus outposts in the United States. Much of their work came with them, as the objects, like their makers, went into exile.

The Busch-Reisinger acquired many objects in its own Bauhaus collection in the decade after World War II, when Harvard served as a refuge for work that might otherwise have been lost in postwar chaos in Europe. Gropius and Charles Kuhn, curator of Harvard’s Germanic Museum (which became the Busch-Reisinger), set about gathering whatever they could. Kuhn reached out to Gropius’s friends among the faculty, students, and their families. Though the Germanic Museum was struggling financially and couldn’t pay artists, Kuhn received art and archival material in abundance.

As the title “The Bauhaus and Harvard” suggests, Muir and Roth want to highlight a relationship between two communities that were first and foremost places of learning. Sometimes the Bauhaus sounds as if it was more fun than Harvard: Itten’s preliminary course began each day with yoga-inspired physical exercises, which Paul Klee called “a kind of body massage to train the machine to function with feeling.”Everyone in the school corresponded with one another using only lowercase letters after master of typography Herbert Bayer, himself a former Bauhaus student, insisted that one does not speak in multiple cases, and therefore capital letters misrepresented sensory experience. The so-called “Fun Department” threw four decadent parties per year, for which students spent weeks designing costumes. Under Klee’s leadership, the metal workshop was accused of producing “intellectual door knobs and spiritual samovars.” Wassily Kandinsky, who taught the wall-painting workshop until the school allowed him to teach unapplied painting in 1925, distributed a questionnaire asking students to fill in a triangle, circle, and square with the colors they felt best suited the emotions evoked by the shapes. There was a right answer.

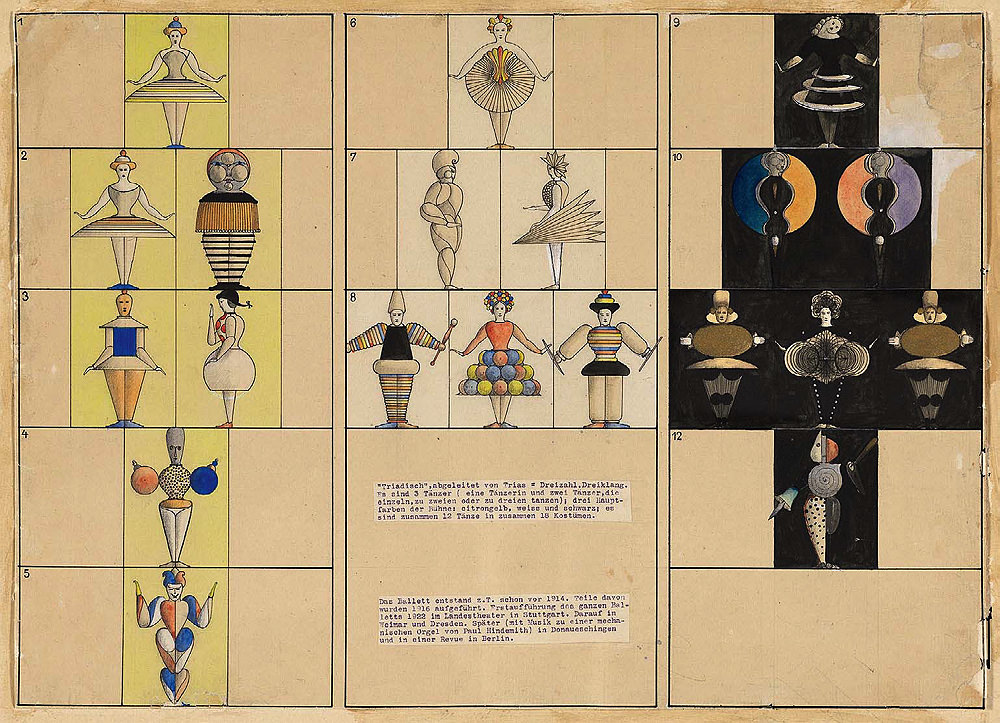

These twirling, technicolor, Michelinesque figures model costume designs by Oskar Schlemmer for his Triadic Ballet (1926).

Some of this fun comes clearly through in the exhibition as in a costume design by stage workshop master Oskar Schlemmer for his “Triadic Ballet,” an avant-garde performance that toured throughout the 1920s, bringing the school needed income. Its costumes pared the human body down to vibrant, twirling geometry, and the dancers wore minimalist, full-face masks, an idea Schlemmer borrowed from eighteenth-century Baroque ballet in his attempt to reduce what had become an expressive, emotive medium to the raw movement of shapes. Some say this silent, robotic performance by anonymized bodies reflected what the Bauhaus thought a human should be.

Some of the charm of the early Bauhaus comes from its wild oscillation between quasi-spiritual Dadaist whimsy and an optimistic political project. Born in the context of a postwar Germany, the Bauhaus was always trying to shake off the aesthetic trappings of the nineteenth-century German Romantic identity. The school’s students and faculty developed sans-serif lettering that challenged the nationalist kitsch of the ubiquitous Fraktur font, and produced the demilitarized chess set, on view in the exhibition, its pieces reduced to geometric forms. If people lived among well-designed chairs and lamps and teapots, the Bauhaus believed, they could absorb good politics aesthetically. Revolutionizing the objects of daily use lurking on kitchen counters was the ultimate grass-roots attempt to change the world.

The Bauhaus dreamed on the largest scale in its architectural projects: practitioners wanted to build buildings that could serve as infrastructure for new social relationships, to change life in society by changing the environments in which it took place—as if architecture and everyday objects might be able to abstract nationalism and classism and the seeds of fascism out of existence, reducing past and future wars to triangles and circles and squares. “We exist! We have the will! We are producing!” wrote Schlemmer.

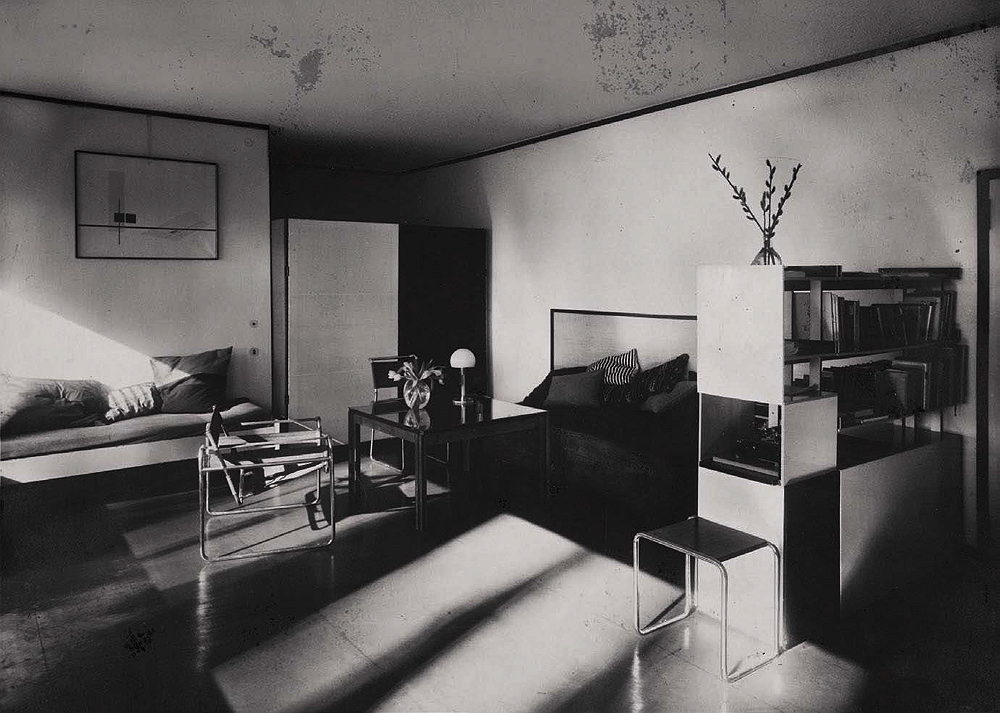

The living room that photographer Lucia Moholy shared with her husband, László Moholy-Nagy, in the master’s housing of the school’s building in Dessau (1925)

Photographer Lucia Moholy’s image of the living room she shared with her husband, László Moholy-Nagy, in the Bauhaus Dessau school building is one of Muir’s favorite pieces. Photography played an unconventional role in the Bauhaus: students and teachers viewed the camera as an experimental perceptual tool, and believed that making photographs could “provoke a fresh rapport with the visual world,” as Moholy-Nagy, who taught the school’s metal workshop, put it. In the exhibition image, Moholy is “looking at the space very skillfully, arranging the furniture herself,” says Muir. The objects and the way the light falls over them are choreographed to reveal the contours of the ideal modernist life, as lived by one of its masters in a building designed by its founder.

László Moholy-Nagy worshipped all things mechanical; prefiguring Andy Warhol, he once placed an order over the phone for a set of geometric paintings he wanted a sign factory to make for him. When he arrived at the school in 1923, Gropius was calling for a merger between art and technology. That year, the Bauhaus turned from the artisanal production of a few objects toward mass production of affordable everyday objects. The school, invested in the politics of collectivity, wanted to speak with one aesthetic voice—but “Authorship was a pretty thorny issue in the Bauhaus,” Muir says. Publicly distributed work, many felt, should represent the brand rather than an individual. Nonetheless, cults of personality were rampant, and the reputations of a handful of workshop masters grew.

Mostly the politics of collectivity came at the cost of women, whose work was often not properly attributed to them, risking their erasure from the school’s legacy. Gropius himself famously made numerous prints from a set of Lucia Moholy’s negatives, and ultimately gifted them to the Busch-Reisinger without her permission. (Her name and the phrase “Reproduction forbidden without permission” was crossed out on the back of at least one print and replaced by Gropius’s signature stamp.) She believed they had been lost in the war.

Bauhaus practitioners wanted to build buildings that could serve as infrastructure for new social relationships, to change life in society.

Muir and Roth could have easily filled the galleries from Harvard’s collection alone with charismatic masterpieces by key figures, or turned the show into a shrine to Gropius—in the history of architecture and design at Harvard, all roads seem to lead back to him—but they are both excited to broaden the field a bit. “To have the chance to take things where we often don’t know who made them and to give them this kind of moment—I think it’s really exciting,” Roth says. “We’re not afraid to say we do put [such pieces] on par with some of the works of the masters.”

The conflict over authorship revealed how the Bauhaus was torn between the desire to create seductive, shiny design objects and the austere pragmatism of Russian Constructivism, which used art as a kind of research for industrial strategy: the school wanted to erase class divisions and make beautiful things. By these metrics, it failed. Its adherents presumed that those whose lives they hoped to improve shared their taste. Ultimately the German middle class preferred traditional, ornate things that made them feel wealthy. Avant-garde objects deliberately designed to look mass-produced, it turned out, didn’t appeal to the masses.

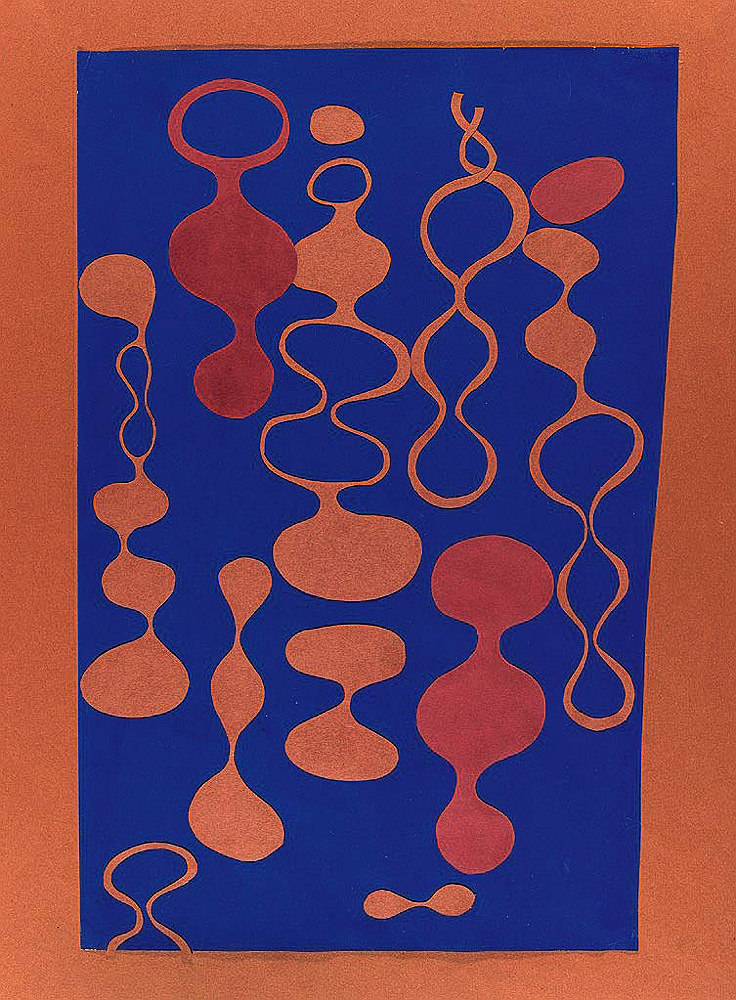

A Ruth Asawa student exercise (in color vibration and figure background) from Black Mountain College, where Bauhaus pedagogy found a postwar home in North Carolina. The sculptures for which she later became known resemble these bulbous forms (1948-1949).

If dormant as an enterprise, though, the Bauhaus lives on through its teachings. Students and faculty members who wound up scattered throughout the United States spread its ideas firsthand. While Harvard snagged Gropius, Anni and Josef Albers took up teaching posts at Black Mountain College in North Carolina, which taught artists such as Ruth Asawa, Robert Rauschenberg, and Cy Twombly, and was the location of John Cage’s first “happening.” With no trustees or deans for oversight, Bauhaus pedagogy was reincarnated and developed throughout the 1940s. Anni and Josef Albers appropriated Bauhaus dogma for a liberal-arts context: Anni, who experimented with cellophane and other new materials in her weaving work, taught her students to let “the threads suggest what could be done with them.” Josef, who often brought eggshells and leaves to class, wanted to let color do its thing autonomously, rather than trying to catch it naked. (He often taught in Harvard’s department of visual and environmental studies during summers.)

Muir and Roth have planned experiences for the centennial that carry the exhibition (on view through July 28) beyond the gallery, including a post-exhibit publication with contributions from faculty, students, artists, and scholars; a March symposium at which scholars will present new research on aspects of the collection; a film series curated by Professor Laura Frahm; and a series of workshops at the Museums’ Materials Lab. A biography of Walter Gropius by Fiona MacCarthy is forthcoming from Harvard University Press in April.

U.S. interpretations of the Bauhaus have shifted over time to gel with the contemporary political moment. In the 1970s, the school’s modernism was derided as a totalitarian aesthetic; in the mid 1940s, Americans held up faculty emigrés and their work as justification for the Marshall Plan—there was still much to be salvaged! How Bauhaus ideas were made palatable in their new transatlantic setting is perhaps best illustrated by a 1944 radio play about Gropius written by Jay Bennett as propaganda for the United States War Information Bureau. A fictional watchman working at the Fagus Factory (designed in part by Gropius and built between 1911 and 1913) admiringly thanks him for his work: “Here is a good place where men and machines get together.” To mid-century America, the Bauhaus (at its best) offered a hopeful version of modern industry, where the architecture of factories could make labor an almost spiritual experience of communing with your machine. At worst, the Bauhaus was a breeding-ground for Communist propaganda.

A small and little-known slice of Bauhaus ideals remains embedded in the Law School. In 1950, the University commissioned Gropius to design the Harvard Graduate Center, the first modernist architectural complex on campus. It was a comprehensive Bauhaus living environment, complete with bedspreads designed by Anni Albers and round wooden cafeteria trays that resisted the military aesthetic of traditional metal ones. To fill out the building aesthetically, Harvard commissioned major works from Joan Miró, Josef Albers, Jean Arp, and others.

Bauhaus art and design in situ in the Harvard Graduate Center. At top, a portion of Hans Arp’s 1950 Constellations II as hung on the wall in Harkness Commons, behind dining law-school students (photograph by D.H. Wright), and above, as displayed in the exhibit

Image courtesy of the Harvard Art Museums and Busch-Reisinger Museum, ©President and Fellows of Harvard College

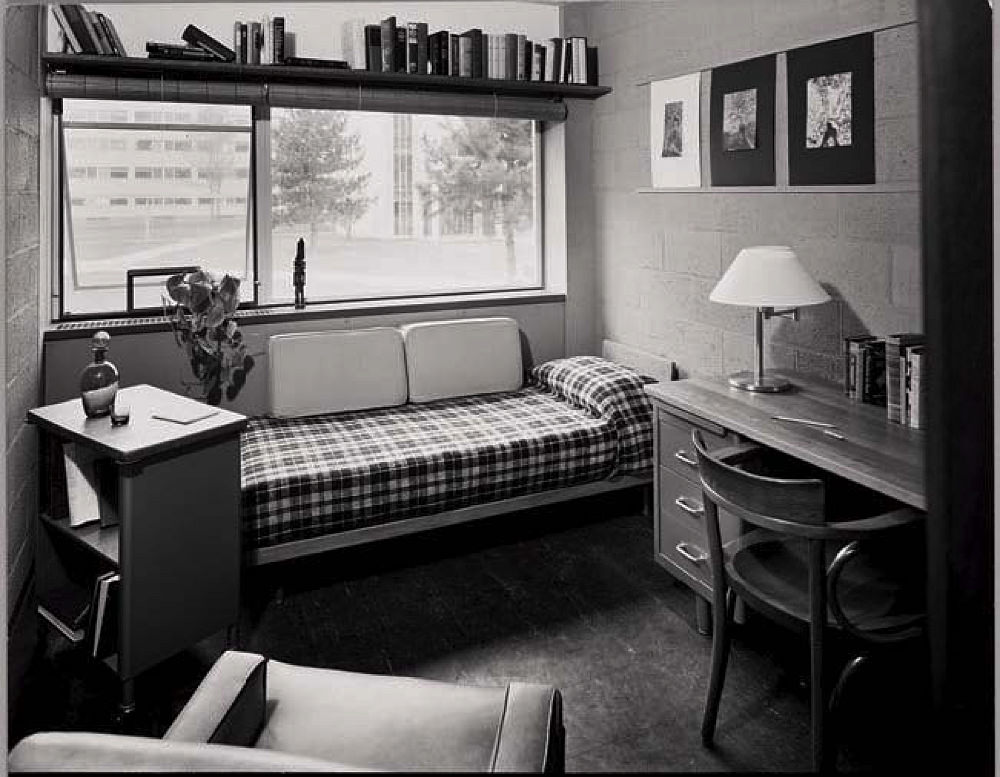

An Anni Albers bedspread in use in a Graduate Center dorm room, c. 1949 (photograph by Robert Damora).

Image courtesy of the Harvard Art Museums and Busch-Reisinger Museum, ©President and Fellows of Harvard College

The center has since been renovated and renamed the Caspersen Student Center. The complex remained full of priceless art until 2004, when most of it was removed for conservation. Muir says the conservation records for the works from the dining room are “terrifying”: they lived among students in the smoky cafeteria and resided behind a number of plants, which were frequently and indiscriminately watered. Hans Arp, creator of the room-sized relief Constellations, intervened eight years after the piece went up to move its panels higher up the wall and out of reach. After undergoing a heroic restoration effort, Constellations appears in the exhibition looking as good as new. A communal living environment may not be the safest place for art, after all: art transforms life at its own risk. The Bauhaus, perhaps, reminds us that it’s not a bad risk for it to take.