Likely distracted by the American Revolution, John Hancock, A.B. 1754, underperformed as Harvard’s Treasurer. When Ebenezer Storer, A.B. 1747, A.M. 1750, took over in 1777, he had to deal not just with his predecessor’s blunders, but with a country lacking standardized currency. A prominent textile merchant, he would hold the treasurer position until 1807, a stabilizing force in a time of upheaval.

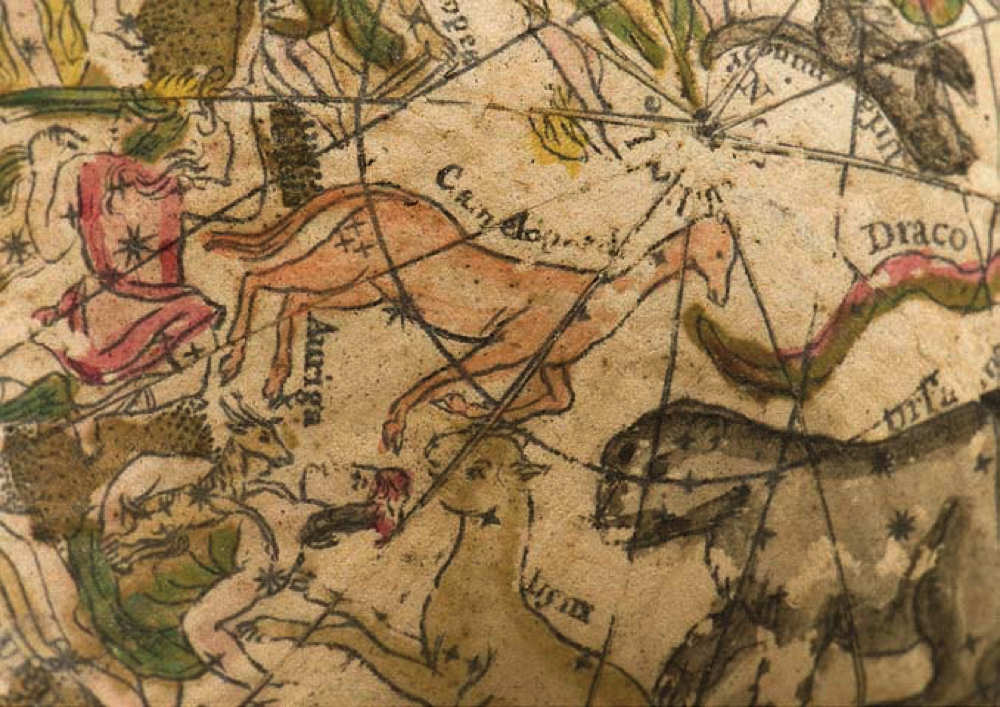

In 1914, Francis Storer Eaton donated some of his great-grandfather’s possessions to the University. One such keepsake was a “pocket globe” about the size of an orange and a bit heavier than a Wiffle® ball. In an 1802 inventory of his instruments and apparatuses, Storer listed the shellacked and slightly cracked knickknack among his least valuable. Two hundred years later, the miniature globe in a shagreen case (lined with vivid images of constellations depicted as animals) is one of two of its kind in the world.

Photographs courtesy of the Harvard University Archives

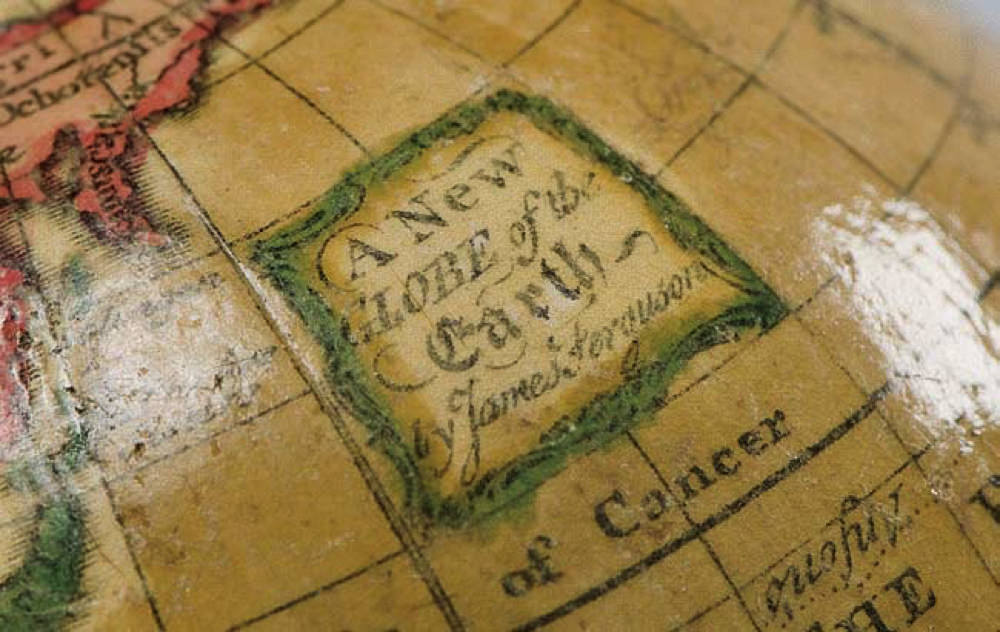

Joseph Moxon, hydrographer to Charles II, produced the first pocket globes between 1659 and 1670, and others continued production through the early 1800s. The globes’ designs were etched onto copper plates and impressed on paper globe gores, which were then glued onto papier-mâché spheres and hand-painted. Storer’s globe was produced by James Ferguson, a Scottish astronomer and natural philosopher who bought the copper plates of prominent cartographer John Senex. Ferguson didn’t buy Senex’s pocket-globe gores, though. He designed his own.

Pocket globes, not made with painstaking accuracy, were of limited scientific and navigational use, but they were a handy reference for schoolchildren and adults. Though inexpensive, they likely served as status symbols. “It is something that shows that you are an intellectual in a sense, that you’re thinking about the world as a whole and not just your local environment,” said Harvard archivist Ross Mulcare. “Having the world in your hands is a metaphor that wouldn’t be lost on them.”

Ferguson’s pocket globes were a bit larger than standard—three inches, not two and three-quarters—and most surviving examples have the imprint of engraver James Mynde. Storer’s doesn’t; the only other Mynde-less example is at the National Maritime Museum in Greenwich, London.

The globe’s exact age is unknown, but clues exist. A dashed line depicting the 1744 circumnavigational path of Commodore George Anson (which resulted in the death of about 90 percent of his crew) runs along China’s coastline and through “The Eastern Ocean.” Poor California, depicted as an island on 1730s pocket globes, is portrayed as a greatly exaggerated peninsula jutting southward into the Pacific. All this indicates an origin around 1755. It couldn’t have been much later: in 1757, Ferguson sold his plates due to poor business management.