New England is filled with peculiar places, and J.W. Ocker plans to find them all. The New Hampshire-based explorer—and creator of the OTIS: Odd Things I’ve Seen travel blog, podcast, and related books—gravitates to anything offbeat, haunting, or macabre. “It’s just my aesthetic,” he says on a crisp morning stroll among the 40 shuttered red-brick buildings of historic Medfield State Hospital—once a pioneering institution that housed chronically ill patients for more than a century.

OTIS began in 2007 as a hobby that got Ocker away from the TV and out of the house, and now features his funny, slightly snarky accounts of many of the more than 1,000 such sites and objects he has visited—across the country and abroad, including hundreds in New England. Old mills, factories, and esoteric inventions fit his catch-all “odd” criterion, as do cemeteries, ruins, historic literary haunts, movie-set locales, kitschy attractions, and purported centers of paranormal events.

Ocker, out and about at the ruins of Bancroft Castle, in Groton, Massachusetts

Photograph courtesy of J.W. Ocker/OTIS

Mostly because he’s an introvert, Ocker seeks eccentric physical sites and objects—not live people, unless they collect oddities—that concretize the complexities, absurd and sorrowful alike, of human nature and history. That explains his fascination with the Medfield site. “Thousands of people walked and worked around here, were in these wards—some for their entire lives,” he says. “It’s not a story in a book. It’s this unique, abandoned world that anybody can access.”

Opened in 1896 as the Medfield Insane Asylum, the Massachusetts institution featured an innovative “cottage-style” design: smaller buildings, a chapel, and a central common—all meant to provide restorative fresh air, sunlight, walking paths, and occupations, such as laboring on its affiliated farm, in a village-like setting. Unlike similar institutions that were closed, razed, or turned into condominiums, the Medfield property was bought by the town in 2014 and opened as a public park. Plans are in the works to re-develop the complex, which includes buildings on the National Registry of Historic Places, while preserving some open space as well as aspects of its critical role in the history of mental-health care in the United States.

Ocker also recommends stopping at the hospital’s cemetery down the road. More than 800 patients were buried there under small plaques bearing only numbers, until the grounds were refurbished, starting in 2005. Then names replaced the numbers on new headstones, and a sign was installed: “Remember us for we too have lived, loved and laughed.” Cemeteries not only reflect local history, they are often “beautiful, quiet places, with funerary art, animals, plants, and trees,” Ocker notes. “Every family trip, I try to squeeze one in.”

Strange monuments are another unofficial OTIS subgenre. Take the two statues of Hannah Duston, an English colonist from Haverhill, Massachusetts, who was captured in 1697 by Native Americans toward the end of King William’s War. She finally managed to escape by killing and scalping nine of her captors, and her story was recorded by the prominent Puritan minister Cotton Mather, A.B. 1678. “Was she a hero, or not?” Ocker asks. “This is about the history of survival. But it’s also the story of a woman killing people. And these are believed to be the first official statues of a woman in the United States.” The bronze figure in her hometown wields an axe, and in the granite monument on a Merrimack River island north of Concord, New Hampshire, she holds scalps—for which she was paid.

Not everything on OTIS is as grim. Ocker raves about the whimsical “Rocking Horse Graveyard” (a.k.a. Ponyhenge), in Lincoln, Massachusetts. Nobody’s sure what engendered the herd of more than 30 plastic and wooden horses in a field on Old Sudbury Road, but around 2010 one appeared, and, over time, “as a sort of community in-joke or light-hearted art display, people have added to it,” he says. “Sometimes I’ll go and someone’s rearranged it all—into lines facing each other, like in battle, or in a circle, or paired off.”

Nature reclaiming the stones of Madame Sherri's Castle, in New Hampshire

Photograph by Erin Paul Donovan/Alamy Stock Photo

Similarly, he appreciates the creative drive behind the Andres Institute of Art, a 140-acre sculpture park in Brookline, New Hampshire. Scattered along trails on Big Bear Mountain, contemporary works offer an active day out, tinged with culture. As Ocker puts it: “Just the fact that there’s something around the next bend beyond poison ivy makes it a much more pleasurable experience than your average hiking trail.” It’s open daily, year-round, from dawn to dusk—and it’s free. Ocker’s picks tend to cost nothing more than gas money.

The idea for OTIS arose when Ocker, out of college and an aspiring writer living in his native Maryland, just wasn’t that happy. “I didn’t really like my life. I didn’t really like me,” he says. To help break a sense of inertia, he began driving to unusual places. Digital cameras were becoming popular, so he took pictures and posted them online with humorous, informative texts. It provided a focus, even meaning, and became “a life-changing time of discovering the world outside myself.”

Kindred curated urban explorer or “off-the-beaten-path” sites like Atlas Obscura, Roadside America, and Roadtrippers are slicker; they have cinematic visuals and battalions of scouts and writers across the globe. OTIS is personal and homegrown—one man’s nearly obsessive project.

By 2008, Ocker had moved to New England, where he was thrilled to find that “Everything is old!” Now living in Nashua, New Hampshire, with his wife, Lindsey, a professional photographer, and three young daughters, he adds, “Just going to the grocery store, I pass three historic cemeteries.My friends who grew up here don’t even know any of this stuff—but it’s all so ripe for exploring.”

He has a full-time day job, as an executive at a digital creative agency in Boston, but OTIS has also morphed into far more than a pastime. He still travels for it, often taking along willing family members, like five-year-old Hazel. In addition to The New England Grimpendium: A Guide to Ghostly and Macabre Sites, and a sister volume focused on New York State (both won top awards from the Society of American Travel Writers Foundation), his book on Edgar Allan Poe-related sites earned an Edgar Award from Mystery Writers of America. A Season with the Witch chronicles the month-long Halloween extravaganza in Salem, Massachusetts, and due out for the holiday this year is his adult horror novel, Twelve Nights at Rotter House. It’s about a travel writer drawn to the paranormal who plans to produce a bestseller based on his time in a haunted mansion. Sound familiar? Ocker laughs. “Yeah, I originally conceived of it as a nonfiction account of staying in a haunted house for a few weeks, and then I realized that would be boring, so I turned it into fiction.”

His worldview easily flexes both ways. Researching his sixth book, now titled Cursed Objects, has brought him closer than usual to notions of psychic phenomena and the spirit realm. He’s intrigued by the staying power of claims like “Ötzi’s curse,” the idea that people linked to the “iceman” found preserved in the Alps “come to a bad end,” he intones melodramatically. “You can try and go see him. Or maybe not. Maybe play this one safe.”

Does he believe in ghosts? He laughs. “I don’t, unfortunately. I like the paranormal, the stories, and the people who chase phenomena. But I just don’t believe in it—and this is coming from a guy who’s spent the night in an abandoned prison in West Virginia, at Lizzie Borden’s House in Fall River, Massachusetts, and in all kinds of graveyards—all the places that ghosts are supposed to be, and there’s not even a single experience that’s even twistable into a real paranormal phenomenon.”

What he likes about the “Dana Ghost Town,” among the communities disincorporated to construct the Quabbin Reservoir in central Massachusetts, is walking through the forest and finding a stone marker: “SITE OF DANA COMMON 1801-1938 To all those who sacrificed their homes and way of life.” Only cellar foundations remain, he explains, but many are posted with placards and images of the buildings that comprised a thriving community—the church, school, and blacksmith. “So it’s another family-friendly place, where you can wander around and understand what was there,” he says. “Some of the cellar holes even have doors you can walk through.”

He typically doesn’t get scared, at least not anymore. Perhaps as a secondary gain from founding OTIS, Ocker has inured himself to common human fears, such as mortality—or small, tight spaces. A big guy, he confesses to having claustrophobia, yet he boarded the pioneering research vessel USS Albacore, now installed on land and open for tours in Portsmouth, New Hampshire. Used from 1953 to 1972, the submarine’s design helped revolutionize the capabilities of underwater military maneuvers. “It’s much smaller than those giant nuclear subs,” he reports, “and it’s terrifying. You see where they slept, on shelves on top of each other, and even just walking around is hard.” One section holds a few multipurpose, foldout tables with checkerboards; “You squeeze yourself out from some tiny slot, and you get to go play checkers. That’s what keeps you from going bonkers,” Ockers says. “It takes a certain special mindset to do that job.”

Over the years, he has become increasingly cautious, traveling to isolated or potentially dangerous places only in the daytime—and he does not condone trespassing or other illegal urban-exploring activities; even so, he has been escorted from a few sites. It’s legal to scramble around Skull Cliff, the ghoulish 2001 mural painted on a 30-foot rockface on a ridge in Saugus, Massachusetts. “To get to it you have to go through car dealerships on Route 1,” Ocker says, “but at the top you can look out over an old quarry and see the Boston skyline.”

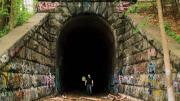

He plays with “pushing beyond the fear” factor at many site visits, and knows that getting active outside on weekends and learning something new about the world benefit himself and his children. Not long ago the family explored the “Clinton Train Tunnel,” built in the early 1900s near the Wachusett Reservoir in Massachusetts. At two-tenths of a mile, it “literally goes from nowhere to nowhere,” he says, but as you walk through it, graffiti-covered concrete walls eerily shift to raw rock, dripping with slimy earthy wetness. And it’s dark. A flashlight was required in the disorienting space as he and his little daughter moved toward a porthole of light at the far end. She somehow lost the head of her doll along the way, and Ocker had to go back to find it.

The Quabbin Reservoir's "Dana Ghost Town" is an archaeological landscape.

Photograph by James M. Hunt/ Alamy Stock Photos

More hauntingly beautiful is Madame Sherri’s Castle, within a forest that bears her name in Chesterfield, New Hampshire. A visit to the once majestic stone chateau, built by a theatrical New York City costume designer, can easily be combined with Mount Monadnock-region hiking, because it only takes a few minutes to take in all that remains of her home, destroyed by fire in 1963: a foundation, a few pillars, and a crumbling, winding staircase. “I tell everyone to go now,”Ocker says, “because places like this don’t stick around forever.”

OTIS rarely veers into such sentimentality. Ultimately, “if it’s truly ‘odd,’ there’s something macabre about it,” Ocker clarifies, toward the end of the visit to Medfield State Hospital. “For instance, there’s this island off Connecticut that has the severed arm of Saint Edmund in a glass case. And it’s a sacred religious object, which I respect and is interesting, but, at the end of it all, it’s macabre. It’s a body part.”

“Dad?”

Hazel, who’s been gamely trotting along, collecting pinecones, interrupts the adults to ask for a ride on Ocker’s shoulders.

“Maybe later,” he says gently, and then adds, “Look around, see this? This is an abandoned hospital.” He gestures toward the boarded-up chapel, the wards, and the swathes of open lawns. “This entire thing is a playground.”

And he means it in the most serious sense. OTIS allows his—and anyone else’s—imaginations to run free.