Democracy and Imperialism: Irving Babbitt and Warlike Democracies, by William S. Smith (University of Michigan, $70). Harvard, widely known as a liberal bastion, was not always and is not only so. Smith, managing director of Catholic University’s Center for the Study of Statesmanship, plumbs the political thought of Babbitt, Harvard’s long-serving comparative-literature scholar. In assessing “the ambiguity of imperialism in democracies”—and Babbitt’s link between that problem and his essential understanding that (in Smith’s phrase) “the quality most required for a successful political order is high moral character in leaders”—the author performs the dual service of rehabilitating an important idea undergirding genuinely conservative thought, and demonstrating its unmistakable application to twenty-first-century America.

The Curious World of Seaweed, by Josie Iselin ’84 (Heyday, $35). The author-artist, who has made readers really look at beach stones and seashells, here goes to town on seaweeds and kelps. The helpful texts, historical images, and her own riveting portraits of their beauty may help readers appreciate their biological importance, too.

The Cosmopolitan Tradition: A Noble but Flawed Ideal, by Martha C. Nussbaum, Ph.D. ’75, RI ’81 (Harvard, $27.95). It is a long way from philosophical discourse on Cicero, the Stoics, Adam Smith, and their successors to “America First” as a campaign-rally slogan. That makes the distinguished University of Chicago philosopher’s engagement with the ideas of world citizenship and universal human dignity—and their practical limits in a material life—timely and urgent, if not light reading.

The Education of an Idealist, by Samantha Power, Lindh professor of the practice of global leadership and public policy and Zabel professor of practice in human rights (Dey Street Books, $29.99). The human-rights scholar-activist (author of A Problem from Hell, on America and genocide, reviewed in September-October 2002) was schooled in diplomatic practicalities as National Security Council leader for multilateral affairs and human rights, and then as ambassador to the UN, in the Obama administration. Her memoir details that work (historians will hash out controversies like those arising from U.S. intervention in Libya), overlaid with her personal priorities (IVF and creating a family with husband Cass Sunstein, Walmsley University Professor, profiled in “The Legal Olympian,” January-February 2015). A useful reminder of the role of diplomacy—and of the challenges faced by those who conduct it.

Choosing College: How to Make Better Learning Decisions Throughout Your Life, by Michael B. Horn, M.B.A. ’06, and Bob Moesta (Jossey-Bass, $25). An education strategist and innovation consultant of the Clayton Christensen “disruption” school (the professor provides a foreword), Horn and co-author Moesta offer a consultant-like approach to figuring out whether to go to college and if so, why, and then, how applicants might attend their “best school.” The book’s chief value may be its operating assumption that its readers are not confined to the tiny minority of 18-year-olds seeking admission to highly selective liberal-arts colleges and universities.

The Empowered University, by Freeman A. Hrabowski III, LL.D. ’10, Philip J. Rous, and Peter H. Henderson, M.P.P. ’84 (Johns Hopkins, $34.95). The flip side of college choice is what choices colleges make. Here the president, provost, and senior advisor to the president of the University of Maryland, Baltimore County, reflect on how they transformed a run-of-the-mill local institution into a nationally acclaimed powerhouse, distinguished for educating minority and disadvantaged students in STEM disciplines. The spirit of chapter 12, “Looking in the Mirror,” seems useful generally—for educators, but also for trustees, civic leaders, and others.

Dangerous Melodies: Classical Music in America from the Great War through the Cold War, by Jonathan Rosenberg, Ph.D. ’97 (W.W. Norton, $39.95). The Juilliard-trained author, now a twentieth-century U.S. historian at Hunter and the Graduate Center of CUNY, has composed a breathtaking exploration of the intersection of international relations and classical music, from the patriotic dismissal of German music during World War I to the embrace of Shostakovich during the Nazi siege of Leningrad and the politics of Van Cliburn’s apotheosis in Moscow during the Cold War. Original, and bracingly written.

Cold Warriors: Writers Who Waged the Literary Cold War, by Duncan White, lecturer on history and literature (Custom House/Morrow, $32.50). As sweeping in scope and ambition as Dangerous Melodies, but in the different medium of literature. As capitalism and communism vied for hearts and minds, and their spies engaged one another, friendships and enmities changed and metastasized, from George Orwell and Stephen Spender to Richard Wright, John le Carré, and Václav Havel: a worldwide engagement of politics and prose.

The Confounding Island, by Orlando Patterson, Cowles professor of sociology (Harvard, $35). The preeminent sociologist (profiled in “The Caribbean Zola,” November-December 2014) here returns to “Jamaica and the postcolonial predicament”: the subtitle, and his birthplace. Democratic but mired in poverty, religious but plagued by violence, lifted up by its indigenous music, the Connecticut-sized island becomes a lens for Patterson to examine globalization, development, poverty, and postcolonial politics in ways that resonate far beyond a place whose inhabitants say (in creole), “We are little but so mighty.”

The Cigarette: A Political History, by Sarah Milov ’07 (Harvard, $35). The author, assistant professor of history at the University of Virginia (tobacco country!), rereads the narrative of smoking, from early farmer-government promotion of the habit and product, through the rise of activist citizen nonsmokers who waged a fight for clean air. It is more than tempting to draw analogies from this careful analysis of interest-group politics to such contemporary challenges as, say, controlling greenhouse-gas emissions to secure the larger atmosphere and the life it blankets on Earth—what she calls, in the context of her research, “the confidence to believe in a different future.”

The Age of Living Machines, by Susan Hockfield (W.W. Norton, $26.95). MIT’s president emerita, a neuroscientist with many Harvard ties, is a clear guide to the emerging synthesis of biology and engineering, resulting in entirely new technologies, with promise for fighting cancer, feeding an ever-hungrier (and -hotter) world, and so on.

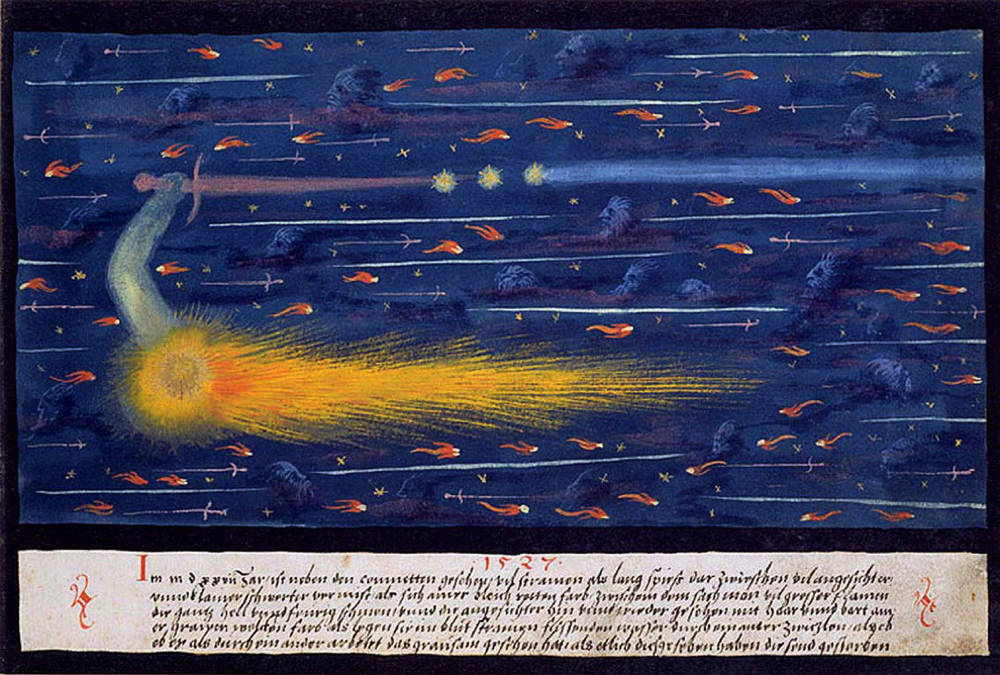

Capturing the cosmos: a comet reported in 1527, from the Augsburg Book of Miracles, by an unknown artist

Courtesy of the George Abrams Collection

Cosmos: The Art and Science of the Universe, by Roberta J.M. Olson and Jay M. Pasachoff ’63, Ph.D. ’69 (Reaktion Books/University of Chicago, $49.95). Wheaton College art historian emerita Olson and Williams College professor of astronomy Pasachoff join strengths felicitously in a large-format tour and celebration of images of the cosmos, from ancient and fine art through scientific illustrations to the (literally) out-of-this-world observations made by the Hubble Space Telescope and other modern instruments.

How the Brain Lost Its Mind, by Allan H. Ropper, professor of neurology, and Brian David Burrell (Penguin Random House, $27). With medical constructs for understanding mental illness now very much contested (see “Misguided Mind Fixers,” May-June, page 73), the authors reexamine the nineteenth-century’s simultaneous experience of neurosyphilis (very much organic) and of epilepsy-like hysteria (with no bodily cause). The contending narratives of psychoanalysis and of psychopharmacology, they suggest, trace to those earlier paradigms—and reformulating them might help in addressing mental ailments today.

Dispossessed, by Noell Stout, Ph.D. ’08 (University of California, $29.95 paper). The author, associate professor of anthropology at NYU, dug into the housing foreclosures that ravaged the Sacramento Valley (and much of the country) in the wake of the 2008 Great Recession. Loan servicers, call-center representatives, and homeowners themselves became enmeshed in a toxic bureaucracy, transforming a financial contract into a moral relationship that colors the lives and views of millions of Americans still. Her account of the “administrative violence” homeowners encountered, instead of debt relief, is an imaginative, informative use of anthropology.

All Blood Runs Red, by Phil Keith ’68 and Tom Clavin (Hanover Square Press, $27.99). A brisk life of Eugene Bullard, a slave’s son who made his way from Georgia to Europe; rose in boxing as the “Black Sparrow”; enlisted in the French Foreign Legion and became the first African-American fighter pilot during World War I; mastered the Paris club scene; served as an Allied spy in the next world war; and found his way back to the United States and the civil-rights movement.