On november 28, 1977, Calvin Tomkins’s biographical word-sketch of artist Romare Bearden appeared in The New Yorker. Prompted perhaps by his gallery, Bearden then decided to cast his own life as a sequence of collages. A 1979 exhibit displayed 28 works, accompanied by titles and short captions coauthored by the artist and his friend Albert Murray, the novelist. A 19-collage sequel followed in 1981. Bearden inscribed the captions on the gallery walls in looping letters echoing his signature.

To draw out the New Yorker connection beyond a mere title, “Profile Series,” Bearden avoided a tell-all history in favor of a concise ironic and anecdotal recall from an oblique angle—from a “profile” perspective, one might say—with a wink. What, he asked, did it take for an African-American boy born in 1911 to begin to find his way as an artist?

Painting © 2019 Romare Bearden Foundation / VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY

He offered one answer during the filming of a documentary, Bearden Plays Bearden, while reminiscing with his friends Murray, Alvin Ailey, and James Baldwin over drinks in a midtown apartment where his new work was displayed. Baldwin asserts the total absence of intellectual and artistic encouragements in the Harlem of his youth: “Everything said no to you. You were taught to despise yourself.” The idea of an Ailey, a Bearden, or a Murray was impossible. “There were no traditions.” “But we did have traditions,” Bearden puts in, quietly. “We had Bessie Smith and Duke Ellington, we had Louis Armstrong. And Jimmy, you and Alvin drew on the King James Bible. You had the rituals that went with them. We all did.”

These traditions affected Bearden long before he saw art as a career. In the Profile series, they afford us glimpses into the black, semi-rural Mecklenburg County of North Carolina, the industrial Pittsburgh, and the vibrant Harlem that so inspired Bearden as he grew up.

The small but potent Miss Mamie Singleton’s Quilt singles out quilts and quilters. Long before he began making collages, or art, young Bearden noticed these bed coverings. In one of the documentary’s outtakes he recalls: “It was a beautiful sight when she would wash them and hang them up in the yard.” Pointing to the collage itself, he remarks: “And there’s also a play of texture—the texture of the wall, the texture of the lady who’s about to take a bath, a little wooden tub, the stove. And I’d call your attention to the pictures [often portraits] on the walls. I used them to show the people who were there and that there was continuity in their lives.”

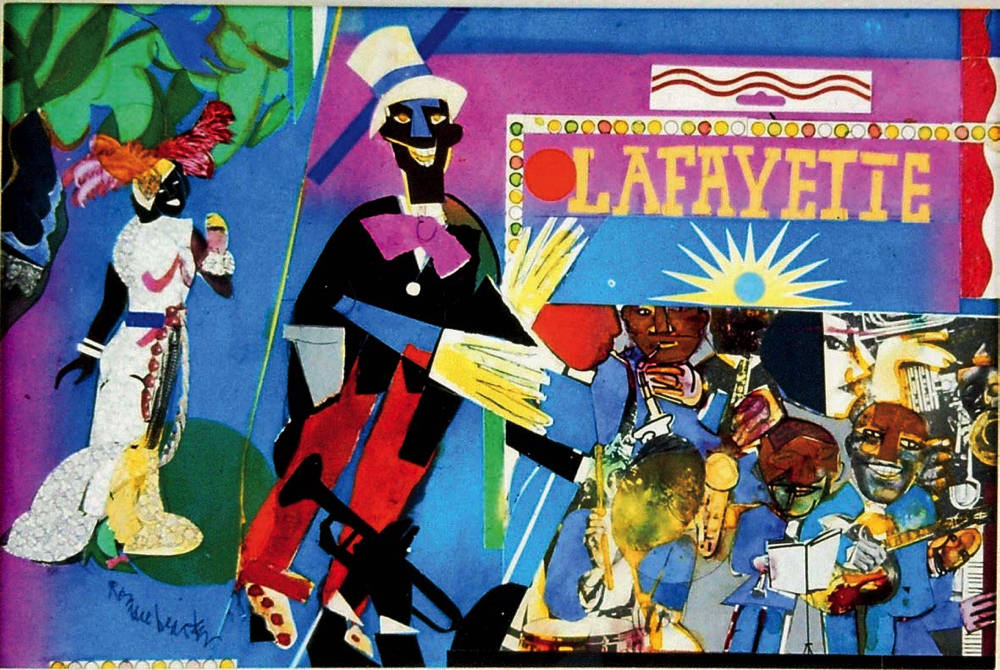

Music’s influence, well documented in Bearden scholarship, resounds in the series with depictions of country and jazz bands, and church choirs rehearsing and performing. The collages Daybreak Express and I’m Slappin’ Seventh Avenue With the Sole of My Shoe are titled after Ellington compositions. But the influence of dance, so important to Bearden’s aesthetic, remains lesser known. One of the Profile paintings, dedicated to the African-American dancer-pantomimist Johnny Hudgins, is captioned, “What he could do through mime on an empty stage helped show me how worlds were created on an empty canvas.” Bearden told his biographer Myron Schwartzman: “When I was a little boy, I was in a theater. The lights went on, the show was stopped, and the manager came out.…Lindbergh had just flown the Atlantic and had landed in France.…[T]he greatest poem written on that flight was done at the Savoy [Ballroom]: the Lindy hop—the dancers throwing the girls, their skirts billowing…the essence of flight. So sometimes we tend to look in the book store or the museum for our history, while neglecting other aspects of it.”

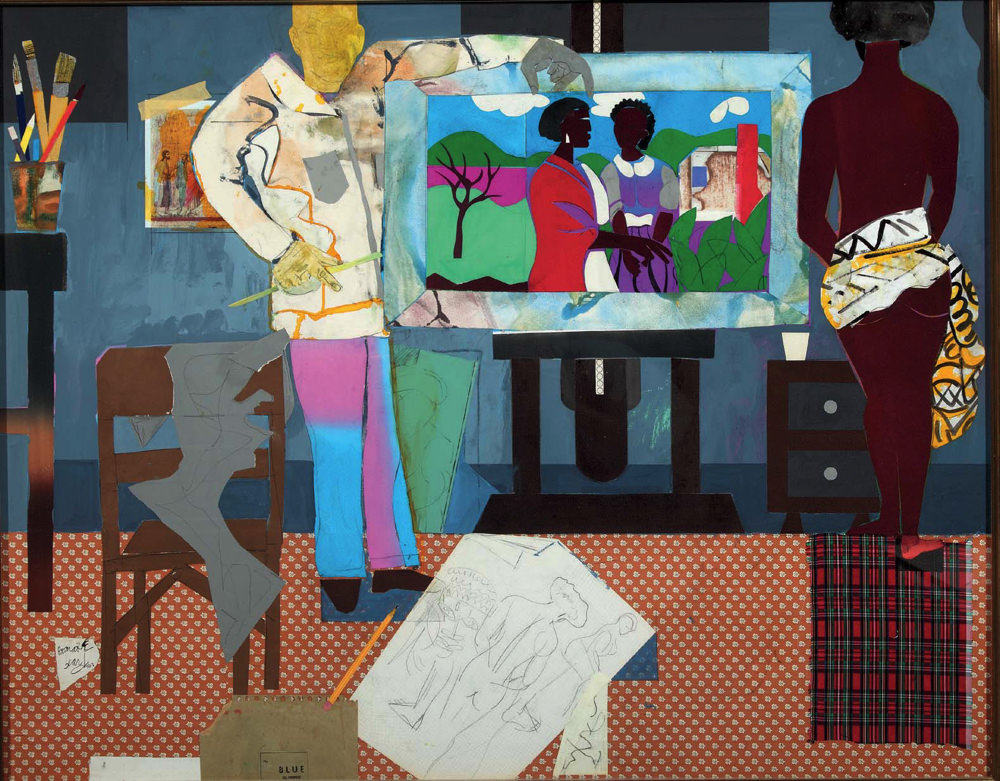

The collage Artist With Model in Studio

Painting © 2019 Romare Bearden Foundation / VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY

Bearden couched his greatest lesson in painting in another, often repeated, story, captured in the Profile series’ centerpiece collage, Artist With Model in Studio. Strolling in Black Manhattan in the 1930s, he heard the repeated jangling of keys, the prostitute’s signal of that era. “There she was,” said Bearden, “the homeliest woman I ever saw in my life. ‘Two dollars,’ she said. And then ‘A dollar’ and then ‘Fifty cents?’ and then at last, ‘Please, just take me!’ ” Telling her she was “ ‘in the wrong profession,’ ” he directed her to see his mother, Besseye, whose contacts extended through Harlem and beyond. Mother Bearden did find Ida a job. To thank Romare, Ida cleaned his studio once a week. He was struggling with a painter’s block (a recurring motif in his artist-as-young-man stories), and couldn’t find a subject to paint. “You told me I was in the wrong profession!” said Ida, observing the blank paper. “Why don’t you paint me?” She could tell by Bearden’s expression what he was thinking. “I know what I am,” she said. “But when you can look at me and see something beautiful, maybe you’ll be able to put something on that paper of yours!” “That,” said the artist, “was the most important lesson in art that I have ever received.” In 1947, Bearden made a journal entry: “Rembrandt took beggars, draped them in exotic garments, and painted them as kings. They were kings, but his greatness consists in the fact that you can see that they were also beggars.”

Artist With Model in Studio shows several influences: Picasso and especially Matisse, Duccio, Benin sculpture, a reworking of one of his earlier “Visitation” paintings into the collage. Here, Bearden has learned to see Ida as a lovely young model while depicting her as a sainted spiritual figure. His overarching project was to show that—viewed with a discerning eye, which is to say, embracing a capaciousness of vision—there was beauty all through the black community, North and South—plenty for the artist to draw on.