“I think I didn’t fully understand that no one knew we had this document,” says Leslie Morris, curator of the Houghton Library’s T.S. Eliot collection, describing the statement from the famous poet that was released just this month, a timebomb rigged to go off more than 50 years after his death.

Written in 1960 by Eliot, A.B. 1910, A.M. ’11, Litt.D. ’47, the three-page typewritten note was opened to the public—as the poet instructed—on the same day that Princeton’s library opened up a collection of letters from Eliot to his longtime friend and muse (and maybe more), Emily Hale. “I wish the statement by myself to be made public as soon as the letters to Miss Hale are made public,” Eliot wrote to his executors in a cover letter accompanying the sealed document.

Eliot first met Hale, a speech and drama teacher at women’s colleges, in 1912, when he was a Harvard graduate student. He began writing to her years later, amid his unhappy marriage to his first wife, Vivienne Haigh-Wood, and the two carried on an epistolary friendship into the 1950s; Eliot also saw Hale occasionally and spent several summers with her and her aunt and uncle at their home in England. But the two never became a couple, even after Haigh-Wood’s death in 1947; instead, a decade later, Eliot abruptly wed his much-younger secretary, Valerie Fletcher. In 1956, Hale donated the letters she received from Eliot—some 1,100 in all, spanning more than 25 years—to Princeton, with instructions that they be kept sealed until 50 years after she and Eliot had both died.

That unveiling had been eagerly awaited ever since. On January 2, the first day the boxes were opened to the public, a handful of researchers arrived at Princeton to begin making their way through the correspondence. One of them, Frances Dickey, an English professor at the University of Missouri who specializes in modernist American poetry, has been blogging daily dispatches on her explorations of the archive. Eliot scholars had long hoped that the collection would shed light not only on the poet’s relationship with Hale, who partly inspired celebrated poems like “The Waste Land” and “Ash Wednesday,” but also on his inner and artistic life more broadly. Austere and intensely private, Eliot tightly controlled what details he released during his lifetime and declared in his will that he wanted no biography written.

But Eliot’s statement, deposited at Houghton Library where his other papers also reside, came as a shock, in more ways than one. “I’d seen this thing”—the envelope containing the sealed document and instructions for its eventual release—“sitting on a shelf in the vault for years,” says Morris, the Vidal curator of modern books and manuscripts at Houghton. “We knew it had to have something to do with the Hale letters, but we didn’t know what the document itself said.” Its existence was unknown to the current librarians at Princeton, who were surprised to hear about it when Morris called them to coordinate the timing of the release, and also unknown to the Eliot scholars whom Morris also contacted. “So,” Morris says, “there was this sense of, ‘Oh my God, we had no idea.’”

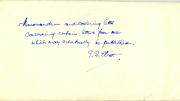

The contents, laid out by Morris in a Houghton Library blog post that shares a full transcript and scanned images of the typewritten statement, were explosive. After declaring himself “disagreeably surprised” to learn that Hale had donated his letters to Princeton, Eliot goes on to give a strikingly harsh chronicle of their relationship from the time he met her and first fell in love. It is a sharp contrast to the newly opened letters at Princeton, which reveal a man deeply smitten: "You have made me perfectly happy: that is, happier than I have ever been in my life,” he wrote in one, quoted by The Guardian. “I tried to pretend that my love for you was dead, though I could only do so by pretending myself that my heart was dead.”

But in the Houghton document, Eliot disavows all of that as the misguided feeling of an immature youth and an unhappy husband, a man in love merely with the idea of being in love: “I came to see that my love for Emily was the love of a ghost for a ghost, and that the letters I had been writing to her were the letters of a hallucinated man.” The statement goes further than that. Looking back, he and Hale, Eliot writes, had little in common, and he faults her for “insensitiveness” and “bad taste” and insufficient interest in his poetry. At one point he states pointedly, “I never at any time had any sexual relations with Emily Hale.” Perhaps the most brutal line comes when he asserts that his marriage to Haigh-Wood, despite its torment, saved him from marrying Hale: “Emily Hale would have killed the poet in me; Vivienne nearly was the death of me, but she kept the poet alive.”

It’s not entirely clear, Morris says, what inspired such intense bitterness. Eliot writes at the top of the statement that he’d always imagined that their correspondence would be made public, preferably some 50 years after they were dead (exactly as happened). “So he obviously saw value in the letters he had written to her,” Morris points out. “And they were written during the most productive poetic time in his life.” Some of his alarm seems to stem from the fact that she donated the letters during their lifetimes, rather than bequeathing them in her will, and he expresses a worry that Princeton’s librarians would not stick to the agreement to keep them secret for the full 50 years. But “Was it only that?” Morris asks. “Just Hale telling him that she was putting these letters at Princeton in 1956, and him thinking about it for four years and then writing this document?”

Eliot burned the other half of their correspondence, the letters that Hale sent to him—a literary loss, Morris says—although he had apparently at one time intended to preserve them. “This document raises just as many questions about motivation as it answers.” When did Eliot decide to destroy Hale’s letters to him? Why did Hale choose to donate Eliot’s letters when she did? What did he hope to achieve with his statement, the last page of which he edited and retyped in 1963? “I find the whole chronology of it fascinating,” Morris says.

In Hale’s own summary of their relationship (a much more tender and understated narrative), she concludes with the idea that the letters will finally bring the truth to light. “At least, the biographers of the future will not see ‘through a glass darkly,’” she writes, “but like all of life, ‘face to face.’” And yet, Morris explains, in his statement Eliot is “saying, basically, ‘Well, I was deluded when I wrote those letters.’”

In the tension between Eliot’s two narratives—one written late in life, from a different perspective and for a public audience, and the other unfolding over time in letters written for an audience of one—lie deep and enduring questions, Morris adds, about archival records and primary sources and the scholarly search for truth. “In working with manuscripts and letters, there’s a tendency for people to say, ‘Well, this is the real thing. I’m reading what he wrote at the time, so it must be true.’” But that certainty is often mistaken. “It may be that there’s no one truth here.”