When the engineer-turned-photographer William Rittase visited Harvard in the fall of 1932, he captured a campus that was in the middle of a radical transformation. President Abbott Lawrence Lowell had recently established the House system—designed to counter the social stratification created by off-campus housing—and, just a few years later, President James B. Conant would open admissions to a wider variety of students (though still primarily white and male) through reforms like merit scholarships and the use of the SAT in admissions.

Rittase’s austere black-and-white photos, on display at Pusey Library this spring, depict a vision of Harvard that still resonates today: an old university full of new possibilities. The exhibit consists of 11 original silver gelatin prints along with a few reproductions, chosen from the 87 images Rittase shot during his visit. He was famous for his unique eye as an industrial and commercial photographer, which gave him a gift for capturing the nuances of grand buildings—most famously in his photos of skyscrapers, which direct the viewer’s eye upward to the clouds. Perhaps it was that futuristic vision that drove Harvard’s administration to hire Rittase: a modernist photographer seems a natural fit to capture a university reinventing itself for the twentieth century. His portraits of Harvard’s brick buildings project the same modern optimism as his skyscraper pictures, highlighting the grand tower of Memorial Hall and the steeple of the newly constructed Memorial Church. Rittase exudes a sense of wonder in every photo, marveling at the intricacies of every place he encounters, as if he cannot quite believe the ingenuity of builders and architects.

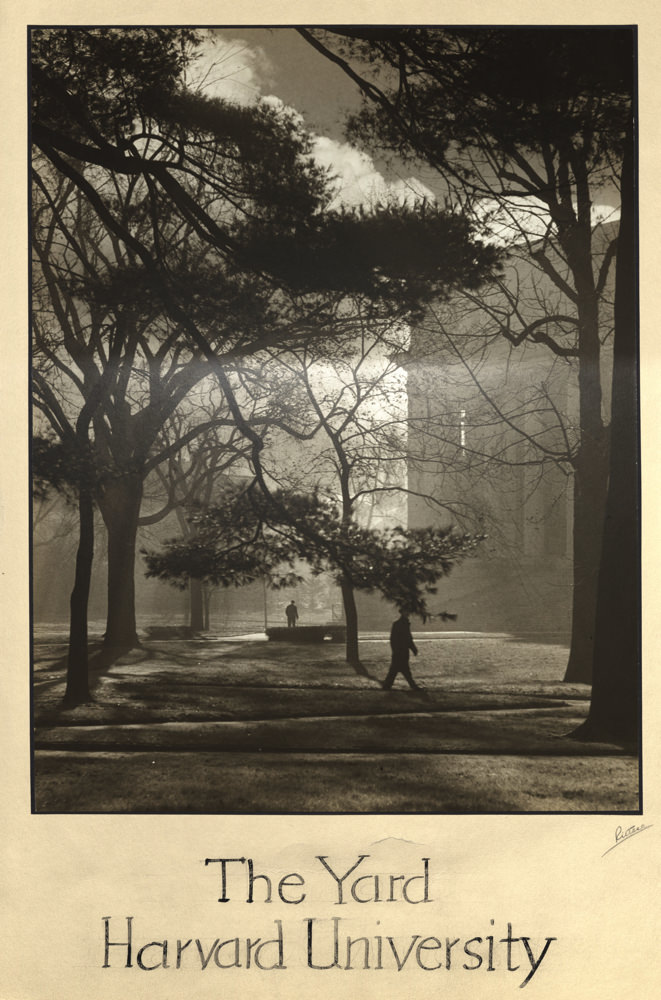

Even when he is not capturing architectural achievements, Rittase manages to communicate hope for a better future in every shot. In one photograph, two human figures emerge from a fog that envelops Harvard Yard, with Widener Library looming in the background. The sun is low in the sky, filling the air with light. That ambient glow, which obscures much of the Yard, seems like an ellipsis. Here is the library, a marker of a traditional past. What comes next?

Harvard Yard

Photograph by William Rittase/Courtesy of Harvard University Archives

On a gray February day four years ago, I toured Harvard Yard for the first time. I did not have any expectations about what Harvard should look like, other than a vague mental image of stately buildings covered in ivy. Like many tourists, I was a bit disappointed on first glance—Harvard’s buildings reflect a smorgasbord of styles ranging from austere Puritan brick to Georgian grandeur to oppressive Brutalism, and only the Business School gets any ivy. Rittase’s Harvard, still steeped in nineteenth-century values, looks a bit more like the vision I had in my head as a public-school kid from Alabama. The walls on either side of Widener’s steps are covered in a thick green pelt of leaves, as is University Hall. It looks like the kind of university that would require a jacket and tie at dinner. There is no sign of modernism, no Science Center or Mather House. The Harvard in these photos seems more imposing, more elegant—and the worse for it. But Rittase managed to see in the past a possibility for growth and change, even in the brick of a building called Memorial Hall.

As I looked through the exhibition of Rittase’s photos, I was struck by how much I’ve come to love our modern Harvard’s eclectic architecture, its total disregard for convention. For all its history, this school has shown a tremendous ability to reinvent itself. I suspect Rittase felt something similar when he visited almost a century ago. His photos fixate on doorways that were brand new at the time, like the detailed bronze carvings of animals on the Biological Laboratories. Those ornaments break from traditional red brick and were, in their own way, as radical as the Science Center. His picture suggests a door into a new kind of future — one that brings new people into the fold, both students from diverse backgrounds and scholars from burgeoning new fields in the sciences and elsewhere.

It’s a vision of new built on old that I admire, and that still exists today. When student activists campaign for ethnic studies or a multicultural center, as they have been doing for generations, they are envisioning another addition to Harvard’s varied landscape of ideas and buildings. It is somewhat disorienting, being in a place where all of its past is visible simultaneously. But Rittase’s photos show that what makes Harvard special is not the buildings, or the plants, but a continual process of reinvention.