Two new exhibits at the Bruce Museum, in Greenwich, Connecticut, explore Danish paintings and scientific imaging that help unveil the truth of what we can see.

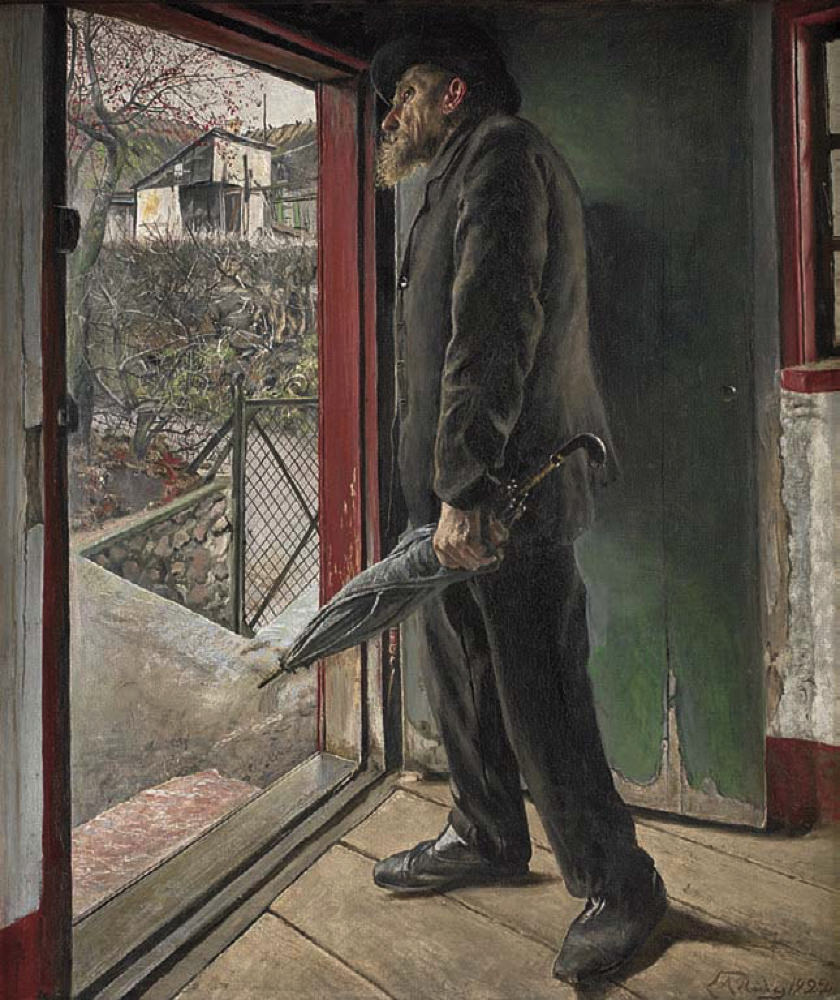

At the core of “On the Edge of the World: Masterworks by Laurits Andersen Ring from SMK—the National Gallery of Denmark” (through May 24), is a heartfelt grappling with modernity. In Has It Stopped Raining? (1922), below, an able-bodied but aged man warily surveys the grayness of the scene outside his door. At the French Windows. The Artist’s Wife, painted in 1897, not long after Ring married its subject, Sigrid Kähler, the young woman in white is surrounded by a blissful, verdant scene. And yet, as chief curator and senior researcher Peter Nørgaard Larsen points out on SMK’s website, the central tree is gnarled, out of place: “I think of [Ring’s] art,” he adds, “as liminal images, pictures that are poised on a threshold.” The artist worked at a time of major cultural change, during a transition from rural to industrial life, and his symbolic yet realist paintings also feature Danish landscapes of crisp coastlines and enchanting Nordic light, along with stirring images of men and women at work in fields and villages.

Courtesy of the Bruce Museum

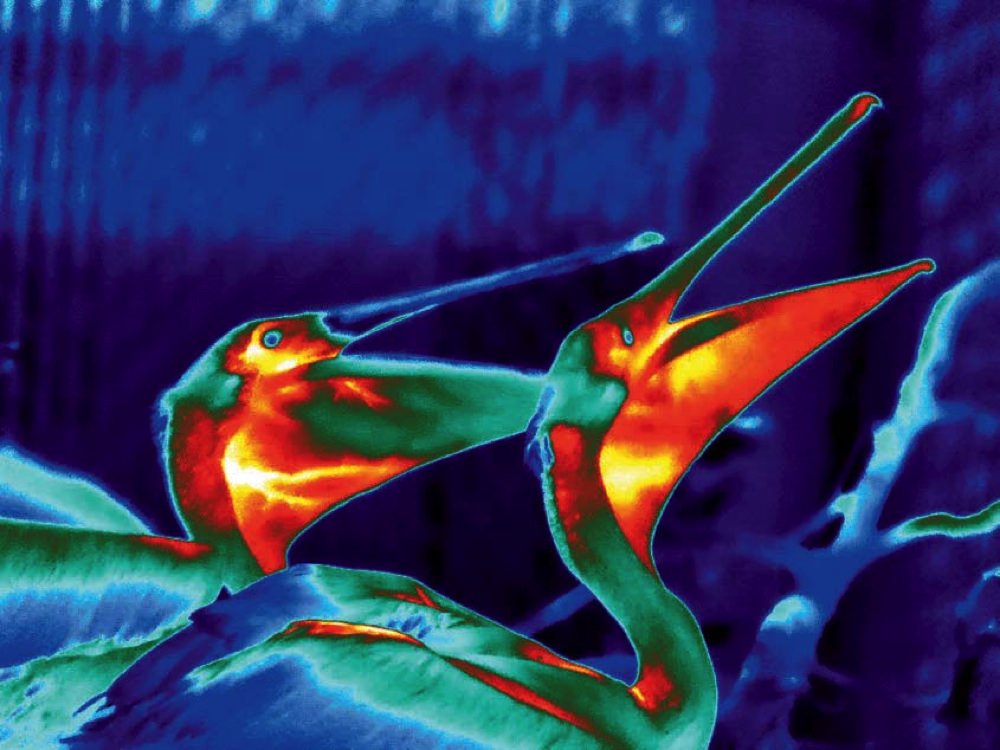

Just as penetrating, although in service to science, is “Under the Skin” (through July 19). The dozen anatomical images, like the thermal imaging of pelicans and their pouches and the cleaned, stained roosterfish specimen, reveal that “nature is full of beauty, at scales great and small,” notes museum curator of science Daniel Ksepka. “While each represents a research breakthrough, these striking, and, in many cases, prize-winning images, can be considered art in their own right.”

Courtesy Dr. L. Witmer, Dr. R. Porter, and Dr. G. Tattersall

Take the patterned microscopic structures of a 10-ton dinosaur’s bones, or the stunningly intricate CT scan of a hog-nosed snake in the midst of digesting its prey. These designs of pure nature—and those of Ring’s sensitive, evocative depictions—reveal the true fragility of universal life forms.