When a colleague chanced upon a stray medieval manuscript page in the Harvard Theatre Collection in 2018, then-Houghton Library curator William P. Stoneman knew whom to call: Peter Kidd, a medieval-art expert. Kidd’s detective work identified the page as a leaf from a fifteenth-century illuminated book crafted for the French diocese of Rennes, a volume that had been thought lost.

Book-breaking is not limited to eBay. In the sixteenth century, manuscript pages were sometimes turned into jam-jar covers and book-jackets, or used as gun wadding. In the nineteenth century, a passion for medieval art motivated the English art historian and social critic John Ruskin to remove leaves from volumes to frame for display or give to friends. His journals record at the turn of the year 1854: “Cut out some leaves from large Missal”; “[p]ut two pages of missal in frames”; “[c]ut missal up this evening; hard work.” In the mid twentieth century, American art historian Otto F. Ege cut up 50 volumes in his own collection and reassembled the leaves into boxed sets to sell as an educational venture to universities and libraries. He believed that the “thrill and understanding” of holding a medieval manuscript leaf justified his action.

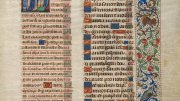

Detail of manuscript

Manuscript courtesy of Houghton Library/Photograph by Harvard Library Imaging Services

Peter Kidd identified Houghton’s leaf (MS Lat 470) as a page from a Catholic pontifical, a Latin liturgical book that describes sacraments and rites. The leaf provides instructions for a synod; its decorative initial capital shows a bishop surrounded by acolytes. Sister leaves in public and private collections provide clues to its history. The volume was apparently owned by Michel Guibé, bishop of Rennes (1482-1502), and then by his brother Robert, his successor as bishop (1502-1507), whose variant coat of arms appears on sister leaves. Centuries later, Count Olivier Le Gonidec de Traissan acquired the manuscript and exhibited it in 1876. Sometime before 1947, the pontifical was disbound and individual leaves appeared on the market.

Profit, not passion, motivates today’s book-breakers. The sale of a manuscript’s leaves, one by one, may realize more than a complete codex. Sellers may not admit to book-breaking, but the market demand for single illuminated leaves is strong among individual buyers who cannot afford an entire volume. Whatever the motive, book-breaking is lamentable and, some would say, unforgivable.

Digital technology offers a partial response to this unfortunate practice and facilitates research of a book’s content and history. Libraries like Houghton now upload images of manuscript leaves and fragments to websites like Fragmentarium (https://fragmentarium.ms) to reconstruct the pages of books virtually. This virtual “rebinding,” scholars hope, will encourage the identification of sister leaves scattered throughout the world.