On February 23, 1944, Lt. Harriet D. Adams of the Army Nurse Corps, stationed at Will Rogers Field in Oklahoma City during World War II, penciled into her diary, “It’s a queer thing but all nurses get in to the movies free on this post. Nice.” Under that, in ink, she added, “Met Bob Earhart at the movies tonight.” Two months later, she and Robert H. Earhart, then a lieutenant in the Army Air Forces, were married. By June, he was en route to southern Europe as an aerial reconnaissance pilot with the 12th Air Force, 3rd Photo Group, 23rd Photo Recon Squadron, a “Photo Joe” flying missions over enemy territory, armed only with a fuselage-mounted camera. When they parted, they had never seen each other in public in clothes other than their uniforms.

In letters home, written almost every day, Bob Earhart sought to reassure his wife about the safety of his missions spying on German troops and equipment from a Lockheed “Lightning” P-38. “They say these damn Germans are pretty fair flyers,” he wrote. “Oh hell, they don’t stand a chance against my P dash three eight.” He regarded his futuristic twin-engined plane as a kind of talisman to ward off bad luck, but his letters also detail narrow escapes from death, such as when he had to pump down his landing gear by hand when the plane’s hydraulic system failed over water, 75 miles from shore.

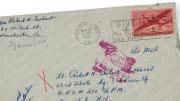

Harriet and Bob Earhart’s letters—now held at Radcliffe’s Schlesinger Library—clear the haze of nostalgia from both battlefield and home front. After Bob left for Europe, Harriet discovered she was pregnant and gave birth to their son, Robert, without her husband by her side. Army regulations forced her to give up her military career. “That shedding of army uniform and ways was pure unadulterated hell,” she wrote to her husband. “I heard everywhere that nurses had no business having babies at times like this.” Both husband and wife fretted about what his return would bring and what their postwar plans would be.

But there would be no postwar life together for the couple. On March 24, 1945, Captain Robert Earhart’s P-38 crashed near Florence, Italy; he died three days later. Harriet would not learn of his death for days, so she kept on writing to him. On the day he died, she wrote about a dream she’d had in which “as soon as you walked through the door you vanished.” He won the Purple Heart and a Distinguished Flying Cross, but his widow had to spend years trying to get a military marker for his grave in his hometown of Pipestone, Minnesota. Seventy-five years after the war’s end, their love is evergreen in this cache of letters and personal objects, purchased from an ephemera dealer, which mysteriously arrived at the Schlesinger bound in white ribbons.