The opening words of Noah Feldman’s latest book, The Arab Winter, are in Arabic:

Al-sha‘b

Yurid

Isqat al-nizam!

The people

Want

The overthrow of the regime!

As he explains in his first sentence, “These words, chanted rhythmically all over the Arab-speaking world beginning in January 2011, promised a transformation in the history of the Middle East.” In English, “the people” are plural and take plural verbs: “We the People of the United States,” begins the preamble to America’s fundamental law, “do ordain and establish this Constitution for the United States of America.” In modern Arabic, Feldman goes on, “the people”—sha‘b—is singular and “the collective noun takes the singular verb.”

“If it did not sound awkward in English,” he writes, “I would translate it as ‘the people wants.’” From a verse of the Qur’an in which “peoples”—shu‘ub—is plural, the noun morphed to the singular as a result of the movement for Arab nationalism of the late-nineteenth and early-twentieth centuries. The movement, social as well as intellectual, envisioned a single nation of all speakers of Arabic spanning the Mediterranean Sea—3,000 miles “from Morocco in the west to Iraq in the east.”

The Arab Winter is about the consequences of the Arab Spring. The series of populist surges between the Decembers of 2010 and 2012, in 10 to 20 countries (depending on how you count), promised to end dictatorship and bring self-government to countries in Northern Africa and the Middle East. But other than in Tunisia, which toppled its repressive dictator and embraced constitutional democracy, the uprising led to civil war, rampant terrorism, or redoubled dictatorship—or to all of them combined. Despite the collapse of the movement, Feldman argues that it should not be judged a failure.

In an admiring appraisal in The New York Times, the journalist Robert F. Worth described Feldman’s argument as “a bold claim” and wrote that he “spins out its ramifications in fascinating and persuasive ways.” Still, perhaps because Feldman is increasingly prominent as a public intellectual and a voice about public affairs—he has a news-oriented podcast called “Deep Background,” writes prolifically for Bloomberg Opinion, and contributes essays to The New York Review of Books—Worth treated the book as a work of acutely informed journalism, not as the scholarly essay on political responsibility that Feldman wrote.

The Arab spring: Tunisian demonstrators in January 2011 show solidarity with the victims of earlier clashes between protestors and security forces, calling for the release of political prisoners.

Photograph by Fethi Belaid/AFP via Getty Images

To him, the uprisings amounted to a reaffirmation of Arab identity. They showed the capacity of the Arab people, whose political lives in different nations had long been determined by conquerors, to make its own politics, even for a short time. The Arab spring showed the people’s capacity to provide the power of example to spur a future when other Arab nations will combine Islam and democracy in their own ways, like Tunisia—though he expects that will not happen for a long time.

Look, again, at Feldman’s use of the first-person in the sentence above about “the people wants”: “I would translate ….” He grew up in Cambridge, Massachusetts, in a Modern Orthodox Jewish home. On a trip to Israel when he was 13, seeing signs in Arabic as well as Hebrew put the idea into his head that knowing both those languages (he had begun studying Hebrew with a tutor at age four) would equip him to help solve problems between Arabs and Israelis. He started to study Arabic when he was 15 at Harvard Summer School with Wilson B. Bishai, a revered teacher in the Department of Near Eastern Languages and Civilizations. Studying Talmud, Feldman learned to read Biblical Aramaic, too. In seventh grade, he started French, and he has since taught himself to read Latin and Greek, learned “graduate-school” German and conversational Korean, and dabbled in Spanish. He is what linguists call a hyperpolyglot.

Feldman has a very good ear, a steel-trap memory, and a curiosity, panoramic and piercing, that reflects his belief that a key to understanding any society and its culture is its lingua franca—the common language used by people of different backgrounds. His love of languages and philology—a combination of linguistics, history, and textual criticism, through study of the structure and historical development of languages—is a part standing for the whole of his approach to scholarship.

The Arab Winter is an interdisciplinary work of history and sociology, as well as linguistics, using insights of political philosophy to explore the right ways of governing in the very different countries of Egypt, Syria, and Tunisia, as well as the Islamic State, the radical militant group, which, at its zenith, controlled large parts of Iraq and Syria and a tranche of Turkey. It is about comparative law in the deepest sense of what law aspires to be.

Feldman writes, “In the interests of disclosure, it may also be worth adding that my own stake in the account and argument offered here grows from almost two decades of trying to interpret the trajectory of political developments in the Islamic world in general and the Arabic-speaking world in particular.” He had previously spent 15 years gaining the esoteric tools and cosmopolitan knowledge to do the interpretation, and, since 1989, he has visited a dozen or so Arabic-speaking countries in the Middle East, on 15 trips. It would have been fair to claim that the book reflects three decades of work.

Into the Law

At Harvard College, Feldman concentrated in Near Eastern languages and civilizations. After graduating summa cum laude in 1992 with the highest grade-point average in his class, he went to Oxford as a Rhodes Scholar and earned a D.Phil. in Islamic political thought in two years, rather than the usual three. He applied to law school because he wanted to get training as a problem-solver and, at Yale Law School, became a protégé of Owen M. Fiss, LL.B. ’64, the distinguished scholar of the U.S. Constitution and of civil procedure, to whom The Arab Winter is dedicated.

Feldman also worked on the Middle East Legal Studies Seminar that Fiss and the school’s then-dean, Anthony T. Kronman, had founded, which still brings law-school faculty members and students together with leading judges, practitioners, and legal academics from across the Middle East to discuss, among other topics, the prospect of democracy in their countries. Fiss says that Feldman’s intellectual ability and writing make him “one of the most remarkable graduates” of that law school in the 46 years that he has taught there—when Yale has been America’s most selective law school and Fiss one of its hardest-to-please assessors of achievement.

After Yale, Feldman clerked for then-Chief Judge Harry T. Edwards on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit, and for then-Justice David H. Souter ’61, J.D. ’66, LL.D. ’10, on the U.S. Supreme Court—apprenticeships especially sought after by young lawyers who aim to become professors. When the second clerkship ended, Feldman began a three-year term as a Junior Fellow at Harvard’s Society of Fellows, which gives young scholars of “exceptional ability, originality, and resourcefulness” the opportunity “to pursue their studies in any department of the University, free from formal requirements.” One of Feldman’s fellowship projects became the first of the four books he has written about Islam and democracy.

In the fall of 2001, he had begun teaching administrative law at New York University School of Law, commuting from Cambridge on leave from his fellowship. He was on a flight from Boston to New York City when two other planes flew into the World Trade Center and a global war ignited. Throughout the Muslim world, the U.S. government and the West had long sought to defend against Islamic fundamentalists by supporting dictators who suppressed democracy. The September 11attacks by the Islamic extremist group al-Qaeda were terrorism, not expressions of fundamentalism, but they made clear that support for dictators had contributed to disaster engulfing much of the world. In casting its terrorism as jihad, however—a struggle against the enemies of Islam—al-Qaeda badly tarnished Islam’s image.

In After Jihad (2003), Feldman threw himself “into the center of an unruly brawl now raging in policy circles over what to do with the Arab world,” as the journalist Jonathan D. Tepperman wrote in a New York Times review. Feldman advocated for American and Western intervention on the side of democracy with “unflinching insistence that democracy in the Arab world should be Islamic in character,” Tepperman went on. Skeptically and prophetically, he pointed out, “The main problem with the choice Feldman offers, however, is his presumption that moderation will ultimately prevail.”

Feldman published After Jihad when he was 33, The Arab Winter this year at 50. In a recent conversation, Anthony Kronman said, “This last book has a kind of sobriety and maturity, without losing the ultimate direction and purposefulness of his argument in favor of Islamic democracy. It’s far and away the most admirable thing he’s written about the Middle East.”

Feldman sees the book as part of his work on government-making and political identity and order: on constitutionalism. “What makes human beings absolutely distinct,” he said, “is that, as Aristotle put it, each human is zoon politikon. To be political in this sense means that humans live under and participate in what ancient Greeks called a politeia—a constitution. The standard translation of Aristotle’s book Athenaion Politeia is The Athenian Constitution. When he says that man is ‘a political animal,’ he means ‘a constitutional animal.’” The core of Feldman’s interest as a scholar and a teacher is in the norms and values that people prize and how they struggle to organize themselves in politics and law to live by them—in the United States as well as in the Middle East.

The Arab Winter is less about forms of government than about the norms and values—“to study constitutionalism is to study a crucial aspect of what it means to be human,” he said—including his own values, tracing back to when, as a teenager, he thought he should learn Arabic to be of some help. The book completes the kind of personal and intellectual project that the oath for Junior Fellows exhorts them to pursue: “You will seek not a near but a distant objective.”

A “Ranger,” not a “Tunneler”

Feldman returned to Harvard in 2007 as Bemis professor of international law, and in 2014 was named to his current chair, honoring Supreme Court justice Felix Frankfurter, LL.B. 1906, LL.D. ’56—a law school professor from 1914 to 1939, with leaves to work in government. Feldman’s bread-and-butter courses are about American constitutional law and about the First Amendment, plus seminars on a variety of other topics. In the 2020-’21 academic year, in addition to teaching about the First Amendment and its clauses on religion and on free speech, he plans to teach a seminar on Jewish law and legal theory in his role as director of a program on Jewish and Israeli law.

In 2010, meanwhile, he had become a Senior Fellow of the Society of Fellows and a mentor to Junior Fellows. The fellowship has largely evolved into a glorious postdoc. “It’s an opportunity to take the sort of intellectual risks that a tenure-track position would rarely allow you to do,” said Rowan Dorin, an assistant professor of history at Stanford and a Junior Fellow from 2015 to ’17. Feldman is matter-of-fact about that risk-taking: “Three years give you enough time to start projects, to see them fail, and to go back to square one and start again.”

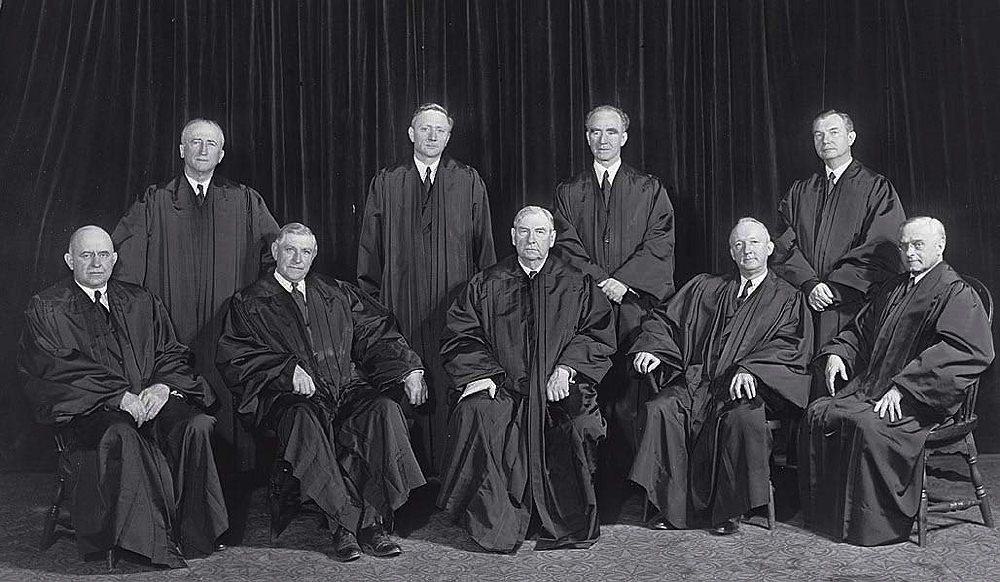

The Supreme Court of Scorpions, 1941. Seated, from left: Justices Stanley F. Reed and Owen J. Roberts, Chief Justice Harlan Fiske Stone, and Justices Hugo L. Black and Felix Frankfurter; standing, from left: Justices James F. Byrnes, William O. Douglas, Frank Murphy, and Robert H. Jackson

Photograpy courtesy of the Library of Congress

The enormity of the challenge and the joy of the hunt for Junior Fellows make Feldman ebullient. A Junior Fellowship is an invitation to join Harvard’s Life-of-the-Mind Society, in which Feldman has a long-term membership: in July this year, he became the chair of the Society. He called it “this institution I really deeply love”—“this little sanctuary of the University where the pursuit of knowledge for its own sake is the highest value.”

The values it represents to him have shaped his career: “convivial intellectual community with people from many very different backgrounds; interdisciplinary creativity and collaboration; openness to new, unorthodox ideas; pursuing solutions to long-term questions that really matter for the world; generosity to colleagues and across generations; nurturing originality to encourage risk-taking; and belief in sustained, in-person conversation as a central element of the good intellectual life.”

In his second sequence of books, Feldman says, “I’m trying to tell the story of the U.S. Constitution through ideas.”

A startling aspect of Feldman’s writing is how little is traditional academic scholarship. “I hugely value that genre,” he said, “and I’m a big consumer of scholarly writing of my colleagues and of people in lots of different fields. I get a large amount of nourishment and learning from that scholarship. But I ended up feeling that, for me, the amount of intense work that one has to put into scholarly journal writing—especially law-review writing, to do it at the highest level—doesn’t necessarily yield the ability to communicate with the largest number of people. This is a challenge that everybody who does scholarship has to face and has to resolve in her or his own way. The best academic scholarship is a conversation among a tiny number of excellent and well-trained specialists.”

He went on, “I think of the books that I write as contributions to scholarship that are also as accessible as I can make them to a general reader. I work very hard to craft them so that they can be read by a non-scholar with ease and with profit. I’m trying to tell a big-picture story that will make a contribution to scholarship. In one sequence of books, I’ve been trying to tell the story of democracy and Islam in the Middle East. In another sequence, I’m trying to tell the story of the U.S. Constitution through ideas.”

“I’ve been trying” is what grammarians call the present perfect continuous tense, the verb form about something that started but did not finish. The subtitle of The Arab Winter is “A Tragedy.” Feldman writes, “I do not dispute that in many ways, the Arab spring ultimately made many people’s lives worse than they were before. Some of the energies released by the Arab spring were particularly horrifying, including those that fueled the Syrian civil war and the rise of the Islamic State.” The book’s theme is optimistic (“Tragedy,” he writes, “can lead us to do better”), but its main factual conclusion is pessimistic (“The current winter may last a generation or more”). The end has the wintry feel of an elegy—about what might have been in the Middle East, and about the close of his long chapter focusing on it.

“I’m trying” is the present continuous tense, about something happening now, including in the sense of being momentous. Since law school, Feldman has been intensely interested in American constitutionalism. Fifteen years ago, he published the book Divided by God, about the division in the nation’s life “over the role that belief should play in the business of politics and government.” While it was a law-review-type argument, not a narrative, the book’s concentration on history and its use of anecdotes presaged the books in which he is telling key chapters in the Constitution’s story.

The two volumes so far in the U.S. sequence are likely the best known of his eight books. Scorpions: The Battles and Triumphs of FDR’s Great Supreme Court Justices (2010) is a marvel of biography and elucidation about the workings of the Supreme Court three-quarters of a century ago, when it became a truly national institution. It focuses on the years between 1937, when President Franklin Delano Roosevelt, A.B. 1904, LL.D. ’29, made the first of his nine appointments to the Court, and 1954, when Roosevelt appointees no longer made up a majority of the justices. The four greats Feldman wrote about are Frankfurter, Hugo L. Black, Robert J. Jackson, and William O. Douglas. The book takes its title from an observation by the constitutional scholar Alexander Bickel, LL.B. ’49: “The Supreme Court is nine scorpions in a bottle.”

Here is the first paragraph:

A tiny, ebullient Jew who started as America’s leading liberal and ended up as its most famous judicial conservative. A Ku Klux Klansman who became an absolutist advocate of free speech and civil rights. A backcountry lawyer who started off trying cases about cows and went on to conduct the most important international trial ever. A self-invented, tall-tale Westerner who narrowly missed the presidency but expanded individual freedom beyond what anyone before had dreamed.

And the third:

They began as close allies and friends of Franklin Delano Roosevelt, who appointed them to the Supreme Court in order to shape a new, liberal view of the Constitution that could live up to the challenges of economic depression and war. Within months, their alliance had fragmented. Friends became enemies. In competition and sometimes outright warfare, the men struggled with one another to define the Constitution and, through it, the idea of America.

The competition was among four constitutional philosophies: Frankfurter’s judicial restraint—restraint of the impulse to turn political beliefs into legal doctrine by striking down legislation serving reasonable but controversial social purposes; Black’s mix of textualism and originalism, his belief that the Court should enforce only the plain meaning of the Constitution; Jackson’s pragmatism, reflecting his view that the function of the Court is to arbitrate competing interests between the Court and Congress, a state and a citizen, and other elementary players in society; and Douglas’s legal realism, his conviction that, instead of a system of principles, law is partly what judges and others with power do and partly what they say they do, a cover for the preferences they serve in the doing—so the Court should not hesitate to impose its own inclinations.

His convincing account of the Supreme Court’s workings and political nature clarifies how integral that nature is to its character.

As a self-described moderate centrist liberal, Feldman wrote with sympathy yet dispassion about all four. The virtuosity in Scorpions is its explanation of how the backgrounds, personalities, and experiences of the four justices shaped their philosophies and how those philosophies changed the Court from a conservative one resisting America’s liberal turn under FDR into the liberal one that helped remake the nation. Feldman brings to life individual, group, and institutional psychology and group, institutional, and national politics—and their role in the exercise of power.

The book is a legal scholar’s analysis of the Court’s workings, written with the perspective of a biographer and a political philosopher. As Scorpions teaches, the job of a justice is inevitably political. Justices are in the thick of the controversies of their times. Their rulings reflect their understandings of those eras and of politics of the most fundamental kind. The book’s convincing account of the Court’s political nature clarifies how integral that nature is to its character as an institution, to this day. Scorpions is among the best single volumes about the Supreme Court.

The Three Lives of James Madison: Genius, Partisan, President (2017) begins:

In any historical era but his own, James Madison would not have been a successful politician, much less one of the greatest statesmen of the age. He hated public speaking and detested running for office. He loved reason, logic, and balance.

But Madison entered public life at a unique moment, when revolution demanded that familiar institutions be reimagined and transformed. Time after time his close friends, the founders of the United States of America, struggled to find solutions as their hastily made arrangements failed. Each time, Madison retreated to the world of his ideas and books. There, he thought, and worked, alone.

Each time, within a few months, he would emerge with a solution that fit with the theory of a republic and was designed to work in practice. Deeply introverted and emotionally restrained, Madison directed his enormous inner energies into shaping ideas that could be expressed through precise, reasoned argument.

The book shows a similar virtuosity in explaining how the backgrounds, personalities, and experiences of Madison, Alexander Hamilton, and others of the nation’s founders shaped their philosophies and how those philosophies shaped the nation. It, too, is about individual, group, and institutional psychology and about group, institutional, and national politics—the exercise of power in America as it took shape. It contains the disputes over and definitions of power that have persisted through American history to the present.

In what Feldman called Madison’s first life (see my review, January-February 2018, page 56), he imagined the United States as a unified nation rather than a confederation of states and he invented the Constitution and the Bill of Rights to shape it. In his second life, after realizing the Constitution’s imperfections in not being able to avoid the problems of partisanship in government, he invented the concept of a political faction in loyal opposition.

He created the Democratic-Republican Party to combat and defeat the Federalist Party of Hamilton, who read meaning into the Constitution to give power to capitalists instead of to the American people, something Madison hadn’t intended. Madison became an intense partisan. In his third life, despite his distaste for politicking, he became a politician when his faction came to power. As secretary of state to President Thomas Jefferson for eight years and Jefferson’s successor as president for another eight, Madison helped establish America’s place in the world.

The book ends, “With its defects and remedies, its flaws and fixes, constitutional government remains the best option the world has known for enabling disparate people to live together in political harmony. It is Madison’s legacy—and ours.” The book came out toward the close of the first year of the Donald Trump presidency, when there was already ample evidence to question Feldman’s optimism about how well Madison’s constitutionalism had equipped the nation to survive acute partisanship and extreme polarization.

Events since then add up to the worst American crisis since the Civil War. They reinforce the view that this period in American history is gravely testing that constitutionalism’s strength. The parallels between the factionalism of Madison’s time and of today mean that The Three Lives of James Madison does not stand apart from the moment in which it was published the way Scorpions did.

While the Madison book is equally valuable in teaching about the dynamics of constitutionalism—especially about that form of government’s deep-rooted need for renewal—it also shows the risk for a public intellectual when his subject is being tested in real time. When Feldman said insistently, at the end of a 2017 TED talk about the book and about the reliability of reason in taming factionalism, that “It’s going to be okay,” he sounded glibly upbeat. Though that emphasis could eventually prove wisely sanguine, it seems stubbornly naïve today.

He is now finishing his ninth book, Lincoln and the Broken Constitution, about the three most crucial decisions of Abraham Lincoln’s presidency. All revolved around the Constitution: to go to war to force the Confederate states back into the Union; to suspend habeas corpus unilaterally, without involving Congress; and to emancipate enslaved people in the South. All required him to break what had been understood as American norms: Lincoln gave the nation “a new birth of freedom,” as he called the victory the Union fought for, and he led it to take an historic step toward racial equality, though that remains an elusive, still-divisive goal.

Assessing this body of work, some who follow Feldman closely don’t want to be quoted as saying what they believe: that he has squandered his talent, becoming a public intellectual too young, without developing his craft as a scholar and doing work worthy of his gifts; or that, in writing about so many topics, he has failed to fulfill his promise to reshape some field of knowledge. Aside from some comments about Feldman’s arrogance and impatience, the harshest criticism is that he hasn’t developed a theory about constitutionalism as the unifying theme of his work, to rival schools like originalism and textualism that have been influential in the past generation.

Beren professor of government Eric Nelson ’99, JF ’03-’07, a close friend of Feldman’s, responded to the first criticism:

Scholarship is a complicated ecosystem and there has to be room within it for people who have very different scholarly temperaments. There are of course some people who are tunnelers, who just keep digging and digging in the same general spot, and whose ambition is to get their relatively narrow subject right, as deeply right as you can get it. Noah could never do that, and neither could I. I think the work that a scholar does best is the work that he or she is actually excited about and wants to be doing. You can be a tunneler or you can be a ranger, and Noah is definitely a ranger. He’s just too interested in too many different kinds of interesting things to be a tunneler. That’s not what he wants to do.

Feldman responded to the second:

I do have a big theory, though I haven’t wrapped it in a bow that says ‘big theory’ on it. Studying any constitution, we can observe major political ideas that are often in tension and in contradiction with each other, playing themselves out through human agency, including the views and personalities of individual people and the institutions they inhabit. Many thinkers regard tensions about constitutions, played out in what I would call constitutional space, quite differently. They see that space as a place where social movements fight it out for power, or as a domain of normative argument about the nature of what is right, or where other kinds of disagreements play out. I don’t agree with any of those views.

“They’re not sufficiently attuned to the ways that political ideas, institutions, and human beings, who form those ideas and institutions, interact,” he continued. “I see constitutionalism as a social practice that citizens use to manage and negotiate political life, with its conflicting values and interests. My view is that the only way to understand constitutionalism is to regard it as a branch of the humanities, in which we simultaneously look at the ideas and institutions, the historical context, and the people engaging with them. I haven’t asserted that grand claim in an essay, but I’m trying to model that approach in my work.”

His work displays the mix of synthesis and substantive mastery that serious journalists aspire to, and the combination of clarity and eloquence that few scholars display. He writes with the conviction that the most important public position in American life is that of citizen, which makes his fellow citizens the most important audience for his writing about American public affairs. To grasp choices made by the Supreme Court and other institutions of law and government, it’s essential for citizens to know and have opinions about much more than government and law, especially about history, political philosophy, and biography. These are learned best through stories about the development, for better and for worse, of ideas, institutions, and leaders.

“The New Free Speech”

Before committing to the Lincoln book, Feldman tried out a few ideas for his next major project. “The New Free Speech,” as he called it, was one of them. It has engaged him in trying to help meet the kind of immense watershed challenge for constitutionalism that the figures in his histories faced—diving in, once again, to the sort of problem-solving effort he first made two decades ago in the Middle East. Feldman wrote a conceptual essay with that title and presented it in a law-school faculty workshop in January 2018.

The essay wrestles with the biggest free-speech problem in the United States today: how to keep content on social-media platforms like Facebook, Twitter, and others from eviscerating the culture on which democratic government depends. At their best, social media amplify free speech and contribute to a dynamic culture. At their worst, they are havoc-wreaking platforms for conspiracy theories and other ravaging content, with momentous effects like helping Donald Trump win the 2016 presidential election with destructive lies rather than truthful information.

As Feldman framed the issue, the legal concept of “free speech is supposed to enable free expression.” But because that concept primarily curbs the power of government, while social-media platforms are owned by private companies, what they distribute is not curbed by the First Amendment, unless that distribution turns a platform into an extension of government.

Social media themselves, Feldman decided, should find ways to protect free expression….

He was focused on the “problem of what we should do to keep free expression alive even as we embrace new ways of communicating.” Under U.S. law, Feldman emphasized, “social media companies have the complete right to regulate, censor, limit, and shape users’ speech however they like,” because “corporations have the right to control any and all speech that takes place on their privately owned social-media platforms.” He regards Facebook and other social media as today’s equivalent of TV, radio, and newspapers when they grew influential: he was adapting the First Amendment to social media in their role as an ever-more influential part of the public square where information and opinion get exchanged as essential ingredients in American democracy.

On a bike ride one day, he thought: Facebook and other social media are under a lot of pressure to avoid outcomes that are morally repugnant. What if they addressed the problem as governments do, giving independent bodies functioning like courts the authority to decide what content is acceptable and what is not? Social media themselves, he decided, should find ways to protect free expression—and he made a proposal to Facebook, the world’s largest social-media platform, with more than 2.6 billion users who send out an average of 115 billion messages a day: “To put it simply: we need a Supreme Court of Facebook.”

The legal scholar Kate Klonick recounted in the Yale Law Journal that “the concept was also in the works at the company,” to give people who don’t work for it the final call on what should be acceptable in a global network. This past May, Facebook announced the tribunal’s initial members. Called an “oversight board,” its initial role is to review Facebook decisions that remove from its site content the company sees as violating its community standards against hate speech, graphic sexuality, promotion of violence, and other offensive material. The board has the power to overturn those decisions. For the past two years, Feldman has helped shape the board as a paid consultant, with the aim of helping Facebook develop the tribunal into a respected counterweight to censorship.

The board has received very mixed reviews. Klonick praised it as “a historic endeavor both in scope and scale.” The academic and journalist Emily Bell, who directs the Tow Center for Digital Journalism at Columbia, said in an interview with the Columbia Journalism Review that she rolled her eyes about the board being a “Supreme Court”: reviewing appeals of decisions to take down content is a limited role and does not deal with the much bigger challenge of responding to “difficult editorial calls in real time.” She went on, “Facebook wants legitimacy in regulation, rather than correct decisions. The board is a way of signaling that Facebook takes self-regulation seriously, which gives lawmakers an excuse not to regulate it.” The board, she summed up, is “rhetorically useful” for the leaders of Facebook, “without being particularly helpful to the rest of us.”

One way the board is not empowered to help, and so not able to keep morally repugnant content off the company’s platform, is in dealing with the inaccurate and incendiary posts of President Trump that Facebook does not take down. In June, Mark Zuckerberg ’06, LL.D. ’17, Facebook’s co-founder and CEO, reaffirmed the company’s policies not to remove them, citing its support of free speech. A group of former employees, in an open letter to Zuckerberg, called his position a “betrayal” of the company’s commitment to maintaining a space where no one, not even the president, gets special treatment.

Twitter took a prominent step in the opposite direction by, for the first time, adding a label on a Trump tweet claiming: “There is NO WAY (ZERO!) that Mail-In Ballots will be anything less than substantially fraudulent.” The label, marked by a big exclamation point, said, “Get the facts about mail-in ballots.” Clicking on it led to statements like, “Experts say mail-in ballots are very rarely linked to voter fraud.” In response, Trump reacted like an autocrat punishing his enemies. He signed an executive order called “Preventing Online Censorship,” which exposes companies to potentially crippling financial liability for other offensive content on their platforms.

Last February, Feldman debated Jameel Jaffer, J.D. ’99, the director of Columbia’s Knight First Amendment Institute, which seeks to defend free speech in the digital age. (I worked there part-time as an editor after it launched in 2016, until the summer of 2019.) Their exchange was framed by the case Knight Institute v. Trump, in which the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit ruled in 2018 that the president’s practice of blocking his critics from his Twitter account violates the First Amendment.

As Judge Barrington D. Parker wrote, the president uses his Twitter account “as a primary vehicle for his official communications,” including “to make official statements on a wide variety of subjects, many of great national importance.” By engaging in dialogue with other users on Twitter, he turned his account into a public forum covered by the First Amendment.

In The New York Times, Feldman criticized the ruling—a liberal taking a position favored by legal conservatives. “This is the first time, to my knowledge,” he wrote, “that the First Amendment has ever been applied to a private platform” like Twitter. That might seem “sensible, even exciting,” he went on, because “social media is where we do our political talking” so “it would seem logical to bring the Constitution to bear there.” The problem, he continued, “is that applying the First Amendment to social media will make it harder or even impossible for the platforms to limit fake news, online harassment and hate speech—precisely the serious social ills that the world is calling on them to address.”

In effect, Feldman was arguing that, in seeking to have the law protect the free speech of those blocked from the Trump Twitter account, the Knight Institute was laying the groundwork for what Trump seeks in his executive order: a regime where social media companies are limited in their ability to decide what speech and which speakers are allowed on their platforms. Feldman’s view was that there is nothing public about the Trump Twitter account, despite how he uses it. He saw the decision in the Knight Institute case as trespassing on Twitter’s prerogatives as a private company. To him, the decision was an affront to Twitter’s First Amendment rights.

Jaffer’s view was that the case was much narrower than Feldman makes it out to be: the case was about Trump’s use of Twitter, not about Twitter. From his perspective, the Second Circuit’s ruling was an important reaffirmation of the most basic First Amendment principle: that a government official cannot lawfully suppress speech because he dislikes its viewpoint. Jaffer rejects the argument that the ruling infringes on Twitter’s rights. It’s “audacious but misguided,” Jaffer said, “to say that Twitter’s First Amendment rights are violated by the enforcement of the public-form doctrine against the president.” A ruling that construed Twitter’s First Amendment rights that broadly would have far-reaching implications, he said. If Feldman’s view were endorsed by the courts, he argued, “it’s difficult to imagine what regulation of social media could possibly survive a First Amendment challenge.”

Regulation may well be necessary to protect speakers in an increasingly perilous public square from other speakers—from being discredited by trolls and drowned out by distorted and fake news—and, as crucially, to protect listeners from all that toxicity constantly flashing around the globe in milliseconds. The view of Congress members and others considering regulation is that the lip service Facebook pays to free speech is of scant use because the company is in the business of selling advertising, not providing free speech.

In mid June, a boycott organized by civil-rights and other groups called Stop Hate for Profit, with the “Hate” in red for emphasis in its logo, called for businesses not to advertise on Facebook and its subsidiary Instagram during the month of July. The goal was to stop Facebook from “promoting hate, bigotry, racism, antisemitism and violence.” Within two weeks, more than 300 companies, from Adidas, Clorox, and Coca-Cola to Puma, Starbucks, and Verizon, had joined. Within a month, the total was more than 1,000. To these businesses, the utopia of connectedness Zuckerberg had long touted had become enough of a dystopia that it was time for a time-out and a Facebook response to financial and moral pressure to become a much stronger steward of “American values of freedom, equality and justice.”

To the boycott organizers, Facebook and its allies, including Feldman, are on the wrong side of history.

When I asked him in July to comment about all the tumult, he did not address the mounting concern that Facebook is more likely to speed the wreckage of American democracy than its revival unless the platform changes fundamentally. He sounded like a not-very-realistic advocate for his immediate interest, not a scholar working out a solution to a problem even bigger than he had recognized: “The serious challenges that Facebook is facing suggest to me the necessity of moving final decision-making on content away from the company’s senior leadership and to the independent Oversight Board.”

Absorbed in the nitty-gritty of policymaking—in the public square rather than a seminar room—Feldman is also working out his ideas. The process is messy, not tidy, as finished scholarship appears to be, but instructive: he is beckoning us as citizens, as American constitutionalism requires, to join in the debate—with the confidence that reason will prevail and keep the tumult from getting out of hand.