Next to the enormous bust of Karl Marx in London’s Highgate Cemetery lies a small stone marking the ashes of a remarkable woman: Claudia Jones. Born in Trinidad, she immigrated as a child to New York City, where she lived until she was deported to Britain in 1955. She died in London before turning 50—a legacy of childhood poverty and hard, stressful work thereafter.

In an autobiographical letter written just before her deportation, Jones described her experience as a young woman in 1930s Harlem. Sharply aware of the racism that shaped her life and those of her neighbors, she listened closely to the various orators who spoke from soap boxes on 125th Street. Those who most impressed her were the Communists, who were almost alone in acting on the belief that black lives matter. They connected, for example, Mussolini’s fascist invasion of Ethiopia with such American horrors as the frame-up for rape of the nine Scottsboro Boys—“this brutal crime against young Negro boys.”

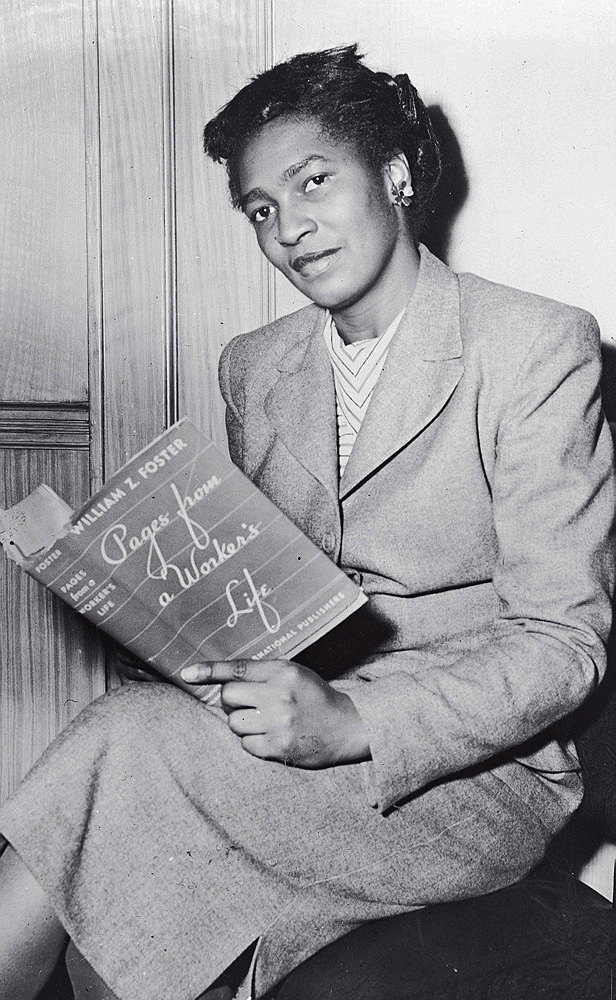

Clauda Jones at the Communist Party's headquarters in New York in January 1948. She was arrested that year and charged with being an illegal alien.

Photograph by Hulton Archive/Getty Images

When Jones joined the Party in 1936, her new comrades quickly recognized her intellectual gifts and charisma. By 1945 she was the Negro Affairs Editor of The Daily Worker. She was also writing theoretical essays that made connections others missed. Perhaps the most prescient, “An End to the Neglect of the Problems of Negro Women” (1949), argued for the inclusion of gender as well as race and class in work for justice: “To win the Negro woman for full participation in the anti-fascist, anti-imperialist coalition, to bring her militancy and participation to even greater heights in the current and future struggles against Wall Street imperialism, progressives must acquire political consciousness as regards her special oppressed status.” Jones proclaimed intersectionality long before it had a name.

When the Cold War and McCarthyism sent Congress and the courts after Communism at home as well as overseas, party leaders were tried under the Smith Act, which made it a crime to “advocate, abet, advise or teach the duty, necessity, desirability or propriety of overthrowing the Government of the United States….” In the second major Smith Act trial, in 1953, Jones and 12 comrades were in the dock at Manhattan’s Foley Square Courthouse, which had become a performance space for the Smith Act show trials. After sentencing, the prisoners were permitted to address the court—an excellent opportunity for Jones to offer an eloquent denunciation of the American system of justice that remains relevant after three-quarters of a century. She identified herself as a lifelong fighter for civil rights, “for full and unequivocal equality for my people, the Negro people, which as a Communist I believe can only be achieved allied to the cause of the working class.” She said she had learned about racism not in Trinidad but in the United States, “out of my Jim Crow experiences as a young Negro woman…the bitter indignity and humiliation of second-class citizenship, the special status which makes a mockery of our Government’s prated claims of a ‘free America’ in a ‘free world.’ ”

The Royal Mail honored Jones and her legacy with a stamp in 2008.

Photograph by Alamy

Deportation deprived Jones at one blow of family, friends, work, and income. The first year was the worst: “It is impossible to be both uprooted and ill,” she wrote to a friend. British Communists did not relish her insistence on confronting racism—or indeed, women leaders. But Jones, recreating herself, discovered new and useful work.

Mid 1950s London was the capital of a nation fraught with tension over race, immigration, and citizenship. With workers needed to rebuild Britain’s industry, jobs were advertised throughout the Commonwealth. In 1948, the arrival from Jamaica of the iconic ship Windrush and its passengers began a wave of immigration from the Caribbean. The newcomers were British subjects, many were veterans of the recent war, but they were greeted with hostility, even violence, in the “Mother Country.” Despite their skills or experience, they were shunted to blue-collar jobs; lodging signs often said “No Coloured,” or worse.

Jones had much to offer her new community. She was accustomed to big cities and cold weather; more significantly, she had no illusions about racism and solid experience in confronting it. Putting her writing, editorial, and management skills to work, she became editor of the West Indian Gazette: a one-page flier when she took over, but within a few years a distinguished center for political organizing and cultural exchange. Though operating hand-to-mouth, the paper covered news from London, the islands, and the wider world. Jones wrote many of the articles and op-eds, drew on such thinkers as Franz Fanon, Nelson Mandela, and James Baldwin, and connected the daily struggles of black immigrants in the U.K. to the contemporary global battle against racism and colonialism, whether in South Africa, Ghana, or the United States. On August 28, 1963, she led a march on the American embassy in solidarity with the March on Washington.

The Gazette also helped her launch the event for which she is best remembered in her adopted country: a 1959 fundraiser for the paper became London’s first Caribbean Carnival (now the Notting Hill Carnival). That joyous occasion celebrating music, dance, cooking—all the arts—was also a strike back at racist violence. In the 1959 souvenir program, Jones wrote of the “pride in being West Indian” that marked the event. Making yet another connection, she recognized and proclaimed the significant relationship of politics and culture.

The little stone in Highgate Cemetery accurately describes Claudia Jones as “a valiant fighter against racism and imperialism who dedicated her life to the progress of socialism and the liberation of her own black people.”