Faculty of Arts and Sciences (FAS) dean Claudine Gay began her annual report for the 2020 academic and fiscal years, discussed today with colleagues at their regularly scheduled faculty meeting, by noting its conventional role as a reflection on the prior academic year and a “report on our efforts to build and sustain a strong faculty and advance the pursuit of our teaching and research mission,” part of a continuing conversation about academic aspirations. But, she noted, “This year is different.” And how.

The resulting report falls into three parts:

- a newsy overview of the year’s unprecedented events;

- a sobering critique of efforts to diversify the faculty, during a protracted period of no growth; and

- an indication of the financial damage inflicted by the pandemic late in the fiscal year ended June 30—and of the dauntingly steeper challenges now at hand.

The meeting itself falls on election day: the conclusion of one of most divisive, high-stakes campaigns in modern U.S. history. The report was made available to faculty members on Friday, October 30, when the weekly Class of 2024 Yard Bulletin advised first-year students, “More masks are available. You can pick up a box from Yard Operations in Weld Hall basement…”—an offer that had nothing to do with dressing up for Halloween the next night. Even the weather was off-kilter that day, as unseasonable, heavy snow pelted Cambridge and the suburbs beyond.

The Year That Was

In writing about the year that was, Gay—who has had plenty on her hands for the past six months—presents a sort of tick-tock that recapitulates the pandemic-driven de-densification of campus, early pivot to remote learning via Zoom, upwelling of protests about racial injustice in the wake of the killing of George Floyd (and academic responses), resumption of research, and FAS’s planning for fall (including a downsized undergraduate cohort in residence) and for longer-term challenges—with stops along the way for the remote Commencement and other notable developments. In addition to documenting this extraordinary period for the future, Gay noted this afternoon how many faculty members had been involved in planning for the fall semester, the resumption of limited residential College education, and other challenges: a testament to the faculty’s breadth of expertise and strength as a community.

Withal, she concludes on an optimistic note about the faculty’s strengths: “Though so much about our daily lives has changed, the events of 2020 brought who we are at our core into high relief. The FAS is a community of unrelentingly high standards, one that embraces everything that can be gained from the best use of expertise and data and is alive with a profound commitment to our academic mission.” That, she continues, “has inspired me and given me confidence in what we can accomplish together, recognizing that many challenges still lie ahead.”

Without being too specific about those challenges, she points readers to the faculty trends and financial sections of the report, where there is much to consider—along with some indications about what the future might hold.

The Faculty: No Growth, and “Underrepresenting the Pipeline”

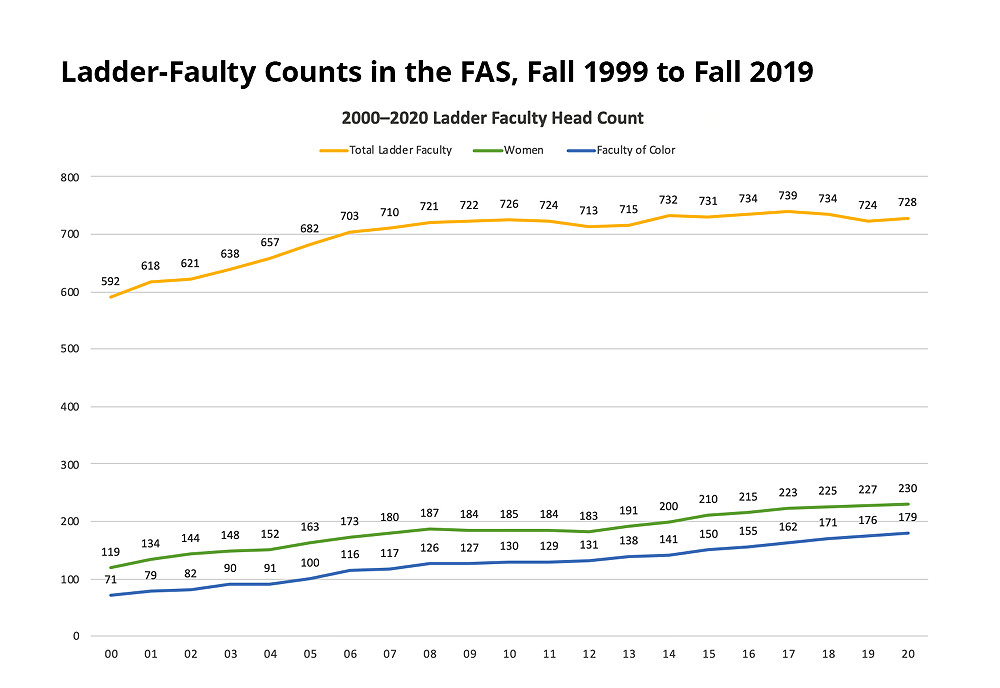

The report from the office of Nina Zipser, dean for faculty affairs and planning, reveals that the ladder-faculty (tenured and tenure-track) ranks rose to 728 in fiscal year 2020, from 724 in the prior year. The peak census (739) was in 2017; for all practical purposes, the faculty cohort has not grown since 2008 (721), when the Great Recession began. Given FAS belt-tightening measures now, that steady state is likely to persist, as Dean Gay has suspended all searches except for a few nearing completion or in areas deemed academically critical.

Turning to faculty demographics, the report notes that the ladder faculty includes 230 women (up from 227 in the prior year) and 179 members of color (up from 176). Some 32 percent of ladder faculty members are women, and 46 percent of tenure-track faculty; faculty members of color are 25 percent of the ladder faculty and 36 percent of the tenure-track ranks. (Because FAS skews heavily toward tenured members—568 of the 728 in total—and because tenure-track members do not invariably become tenured, the ladder-faculty ranks, while encouraging, do not portend an immediate, significant change in the composition of the faculty overall.)

Gay also highlighted professional-development efforts for tenure-track faculty members. The report details initiatives such as the “faculty working group” program, which assembles small groups of tenure-track colleagues to converse, provide reactions to works in progress, share information, and generally attempt to enrich and support one another early in their academic careers.

That said, the report details two significant challenges for further diversifying the faculty and assuring that FAS attracts and retains the best talent available.

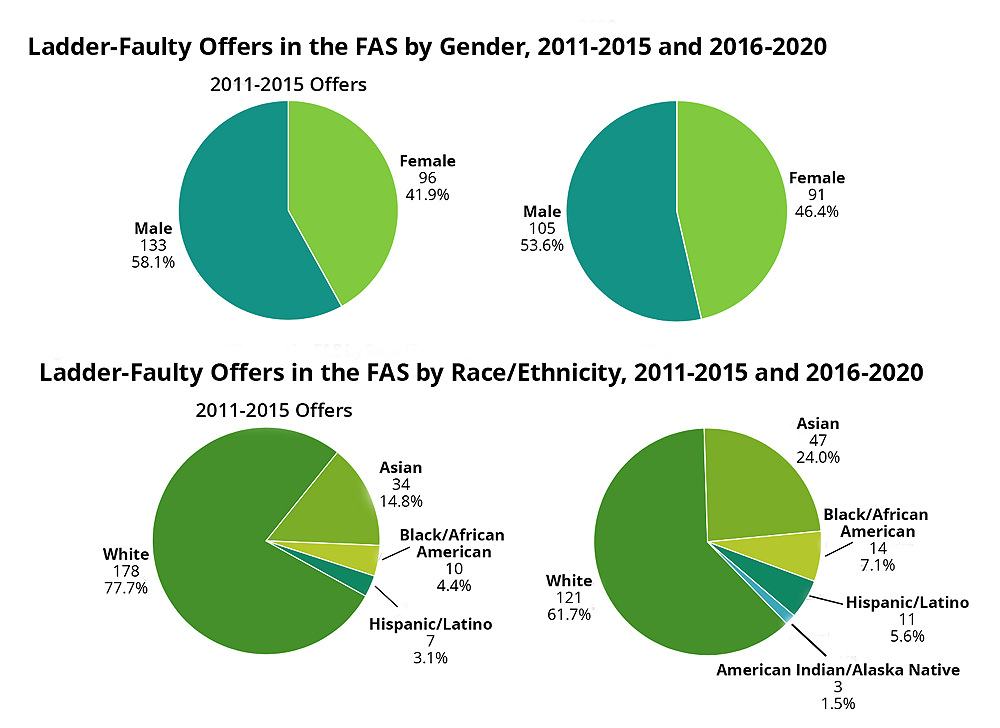

First, it presents data on ladder-faculty offers by gender and by race for the periods 2011-2015 and 2016-2020.

- In the earlier period, 58.1 percent of the offers went to male candidates, and 41.9 percent to females. In the later period, those proportions were 53.6 percent and 46.4 percent.

- For the same periods, candidates made offers earlier were 77.7 percent white and 22.3 percent faculty of color (including 7.5 percent underrepresented minorities); and then 61.7 percent white and 38.3 percent faculty of color (including 14.2 percent underrepresented minorities).

But because the total number of offers declined—from 229 in the first period to 196 in the second—change is coming at a very measured pace. Presenting exhibits that are not in the report, Dean Zipser noted that the ladder faculty as a whole remains 75.4 percent white, 14.6 percent Asian, and just 10.0 percent underrepresented minorities or two-plus races.

Second, despite considerable efforts to broaden candidate pools and attract those who might have been overlooked in the past, FAS’s hiring aligns poorly with at least one raw measure of applicants.

- In its discussion of the applicant “pipeline,” the report notes that the share of domestic U.S. doctoral recipients in 2018 who identified as coming from underrepresented groups averaged 16.2 percent nationwide across arts and sciences fields (16.9 percent in arts and humanities, 19.7 percent in social science, 14.4 percent in science, and 14.3 percent in engineering and applied sciences).

- But for the years 2013 through 2019, only 6.5 percent of FAS’s tenure-track applicants identified as coming from underrepresented groups (ranging from 7.7 percent in social science and 7.6 percent in arts and humanities to 3.4 percent in engineering and applied sciences). As the report puts it, “We are significantly underrepresenting the pipeline.”

- FAS did better in its actual offers, with 9.8 percent of tenure-track offers to candidates between 2011 and 2020 self-identified as from underrepresented groups. Nonetheless, relative to the size of the doctoral pool, the report concludes, “[W]e are still significantly underrepresenting the Ph.D. pipeline.”

Zipser observed that the data mean that for all of Harvard’s strengths and reputation, candidates do not automatically seek positions in FAS. Attracting the best candidates, and broadly diverse ones, is the result of deliberate, hard work. The evidence that FAS does better in diversifying its tenured offers than in hiring for tenure-track positions suggests that when an appointment is considered high-stakes, faculty members put more work into conducting searches rigorously and thoroughly. Making that practice the standard, she seemed to suggest, was an opportunity to achieve FAS’s aims for excellence and breadth in building the faculty of the future.

The Financial Fallout: “Unsustainable” Results

For fiscal 2020, the good news is that the bad news was not as bad as anticipated. The financial narrative in the annual report, from Leslie A. Kirwan, dean of administration and finance, and her staff, and the accompanying unaudited financial statements, note that the pandemic’s financial consequences “occurred in the final quarter of the year and are not readily apparent from a year-over-year comparison.” Accordingly, this year’s narrative illuminates the precipitous downdraft from late winter through June, and then looks forward into this year and beyond, “years that are likely to see significantly greater effects of the pandemic.”

Fiscal 2020. On April 15, the report reminds readers, Dean Gay took several steps to deal with current and anticipated problems: freezing faculty and exempt staff salary increases and bonuses; freezing searches (as noted above); imposing reviews of all proposed new staff positions; suspending and reviewing capital projects; eliminating nonessential spending; and asking faculty colleagues to control research spending where possible.

Those steps had the desired effect. FAS had originally budgeted for a cash surplus of $43.1 million for fiscal 2020, and a consolidated loss according to Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP) of $5.6 million (including the School of Engineering and Applied Sciences, SEAS). Initial reforecasts at the outset of the pandemic showed cash generation shrinking to nearly zero ($2.0 million), and the GAAP loss ballooning to $42.2 million. In the event, the faculty ended up with a surplus of $38.5 million on a consolidated basis, and a consolidated GAAP loss of $15.8 million.

Revenues were essentially flat for the year, after growing at a 4.3 percent compound annual rate for the prior five fiscal years. Expenses rose 2.1 percent—below the five-year trend of 3.2 percent.

What happened? FAS’s largest source of revenue, the endowment distribution, remained unchanged. Compared to the March forecast, a feared collapse in sponsored support for research was largely eliminated, because federal emergency orders liberalized spending, and labs were reopened in June, earlier than expected. The projected decline in continuing-education tuition and fees took place (albeit somewhat less dramatically than feared). So the major swing factors were two: FAS budgeting assumed the pandemic would pinch off philanthropy, but instead, current-use giving came in $16 million better than expected—and even $2.7 million ahead of the original budget for the year—as supporters rallied to help the faculty address its new needs (a phenomenon noted in the University financial report as well). And with most students sent home from campus, the projected $23-million-plus decline caused by refunded board and lodging fees was realized. In all, against a March forecast of a $79-million revenue shortfall for the rest of the year, FAS actually suffered a decline of $38 million.

A good thing, too, because expense savings forecast in March ($41.3 million) came in at only about half that level. An anticipated $8.5 million savings in compensation (signaled in the spring, when the University suggested that layoffs and furloughs were imminent) was not realized, because “A significant decision was made by Harvard and its schools to protect the pay of all workers through the fiscal year”—a decision still in effect as dining, building, and security staff and contracted workers are being protected this autumn. Nonpersonnel savings were achieved, in abundance, as travel bans resulted in immediate reductions of travel and event spending; space and occupancy costs fell by more than $13 million as buildings were closed; spending on supplies and equipment shrank; and so on. Offsetting a significant share of these savings was FAS’s $15-million accounting provision for its share of the costs of the Harvard-wide Voluntary Employee Retirement Incentive Program: 159 of 346 eligible staff members took the offer.

Although FAS and SEAS realized a consolidated cash surplus, some 95 percent of this sum is restricted—meaning that the unrestricted cash surplus, available to support current operations or invest in new priorities, was just $2.9 million. And that, in turn, reflects a prior rabbit pulled out of a hat: FAS’s 2017 agreement with the University to restructure its internal long-term debt (deferring debt payments, to free cash now) yielded $34.3 million. Absent that (diminishing) source of funds, operations produced an unrestricted cash deficit of $31.4 million. On the balance sheet, FAS’s long-term debt continues to increase, from $1.17 billion at the end of fiscal 2019 to $1.23 billion at the end of fiscal 2020: a trend that is baked into the debt restructuring, with $35.1 million of the increase in the year attributable to the agreement, which runs for 20 years.

The financial officers’ bottom line on the 2020 bottom line? “The fiscal year 2020 results are unsustainable.” Almost all the savings realized in the final months of the year were short-term, achieved by “curtailing activities that could not continue during the pandemic, rather than by implementing structural changes.”

Fiscal 2021. The budget for this year has been revised multiple times as assumptions about the endowment distribution, enrollment (and therefore tuition and room and board fees), and new financial support for graduate and undergraduate students in the extraordinary pandemic circumstances changed repeatedly. In its present form (labeled Budget 3.0 in the report), FAS expects to have a consolidated cash deficit of some $43 million for the year, and a consolidated GAAP operating loss of nearly $112 million.

These figures, though significantly reduced from Budget 2.0, represent a calamitous decline from the pre-pandemic assumptions (a cash surplus of $27 million, a GAAP loss of $17.4 million). The improvements from the direst worst-case budget reflect expense savings on compensation (those salary freezes, and the incentivized retirements), control over hiring, and more than $60 million in savings from reducing capital spending and debt service during fiscal 2020 and 2021 (part of a larger, five-year plan to reduce capital spending and debt service by nearly $150 million). Those savings were needed to offset anticipated losses of as much as $120 million in revenue (reduced tuition, room and board fees) and increased costs (purchasing personal protective equipment, virus testing and tracing).

In Prospect

The depressed revenues and elevated expenses associated with the pandemic will abate at some point. But the outlook even for the spring semester cannot yet be determined: FAS will announce in December how many undergraduates will be permitted to return to campus, which will in turn affect how many decide to enroll and the resulting tuition and fee revenues. (In the fall semester, only about 23 percent of undergraduates were in residence, and College enrollment totaled about 5,400, some 1,200 to 1,300 below the norm, as students chose to take leaves or deferred admission).

But in her message to the faculty, Dean Gay was at pains to cite work done by one of her planning committees, led by Olshan professor of economics John Campbell (who has been a Harvard Management Company director and a leader among faculty members in analyzing FAS’s resources), on “FAS financial sustainability.” She did not go beyond saying that that committee’s work “provided analysis and observations that presented new frameworks for tackling the difficult tradeoffs embedded in the FAS financial challenge, disentangling one-time and short-term costs from long-term structural considerations.”

Toward the end of the financial section of the annual report, the committee’s observations crop up again. It is credited with identifying “several issues that transcend the COVID-19 pandemic”—foremost among them, “that continued heavy reliance on endowment distributions to fund the annual budget subjects FAS to…wide swings in financial results.” Indeed, during the year, FAS’s reliance on endowment distributions rose to a recent high of 53 percent of operating revenues, in the University’s calculation. “With lower endowment returns expected in the future,” the FAS narrative continues, “a structural deficit may emerge, potentially of a magnitude that is too great to address with traditional approaches.”

Indeed, the fiscal 2021 budget has had to be built with an assumption of level endowment distributions, versus the 2.5 percent increase per endowment unit owned that applied in fiscal 2019 and 2020. Meanwhile, growth on top of that—from gifts of new endowment funds (FAS’s overall endowment revenue rose 5.2 percent in fiscal 2020)—is tailing off as pledges from The Harvard Campaign are fulfilled. Even the rescaled Budget 3.0 yields deficits that “exceed the reserves available to the dean,” the financial report observes. “Measures to address this gap may include borrowing, decapitalizing the endowment, or making further cuts, all of which entail risks and consequences that need to be weighed.”

Beyond these rather anodyne comments, the report—and Gay herself, in her introductory essay—remain silent about those “long-term structural changes.” The scenario laid out—deficits, declining endowment returns, Gay’s repeated warning of pandemic impacts “in the hundreds of millions of dollars” extending beyond just this year, and the need for associated adjustments in FAS’s operations—begs for details to be filled in.

On one hand, this is the FAS playbook developed by Gay’s predecessor, Michael Smith, who as dean in the aftermath of the Great Recession froze hiring and compensation (thus bending the upward trajectory of expenses), focused colleagues’ attention on maximizing unrestricted cash, and jawboned faculty members into belt tightening. Accompanied, ultimately, by rebounding endowment results and the largess from The Harvard Campaign, FAS righted its ship. Now, of course, it has taken on a lot of extra debt to pay for House renewal and other capital programs; faces an uncertain endowment distribution, at best; and cannot expect another huge capital campaign to replenish the coffers anytime soon.

So it is instructive to parse last week’s announcement about the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences for signs of things to come. In addition to immediate belt-tightening—in the form of reduced doctoral admissions for academic year 2021-2022—the directive from Gay, GSAS dean Emma Dench, and others points to a wholesale review of graduate programs. The size of future cohorts is to be disciplined not only by resources, but by an evaluation of the quality of advising delivered to students, diversity in admissions, and career outcomes for graduates. This is, in short, a possibly transformative reassessment of Harvard graduate education, reflecting not only the pressures brought on by the pandemic, but also underlying changes in higher education and doctoral training.

Several faculty members spoke up about how decisions like reducing or pausing graduate admissions, or other structural changes to address FAS’s significant financial straits, are arrived at and communicated. Some professors called for opportunities to learn more about FAS’s finances, and for the chance to discuss potential solutions, rather than waiting for them to be announced. Dean Gay endorsed those requests, and promised to accommodate them—another sort of structural change for FAS, as it navigates toward putting its affairs on a sustainable footing.

Gay did suggest that with many staff members effectively working remotely, the faculty might well want to look at its use of space: 10 million square feet of facilities, and extensive additional rented quarters in Harvard Square. Over time, if some of the work could be restructured and leases reworked, she and Dean Kirwan suggested, potentially significant savings might be realized. As Kirwan pointed out, for FAS savings imply people (faculty and staff members), space, programs, and enrollments (including, for example investing in further growth of online courses offered through the Division of Continuing Education). Clearly, there is plenty to discuss—and the focus on those structural changes, Gay suggested, is intensifying now that the dimensions of the financial problems are becoming known.

It is not unthinkable that faculty members’ and students’ experiences with online teaching and learning, fresh approaches to classroom use and scheduling, and hybrid residential and remote degree programs might come to the fore, too, as the pandemic brings about real resource constraints, and prompts innovative ways of overcoming them to sustain FAS’s, and Harvard’s academic missions.