In 1936, Elizabeth Bangs Bryant had worked at Harvard’s Museum of Comparative Zoology for a few decades, and her expertise was just beginning to gain recognition. Noted for her taxonomic skills in identifying, classifying, and cataloging spiders, Bryant was busy maintaining and cataloguing the museum’s ever-expanding collections. When a Yankee Magazine editor asked to profile her for their “Smart Yankee” feature, she declined, responding, “My work on spiders is very technical and of little interest to an outsider and I am a very every day kind of a person.”

But Bryant’s “every day,” frequently mundane, work is what made her career so remarkable. For more than 50 years, she spent three days a week in a tidy office on the MCZ’s fourth floor. “I am spending my mornings on what Mr. Banks calls ‘curator work,’ ” she wrote to a friend in 1941, “which in my case means going over the entire collection and adding alcohol where it is necessary. It is a tiresome and disagreeable job but it has to be done. The year that I left it to a student, it was only half done.” The process ensured that specimens would not dry out or be damaged: Bryant had been told years earlier, “Everyone using collections of spiders must realize that what some call fussing makes for keeping the collection in usable condition.”

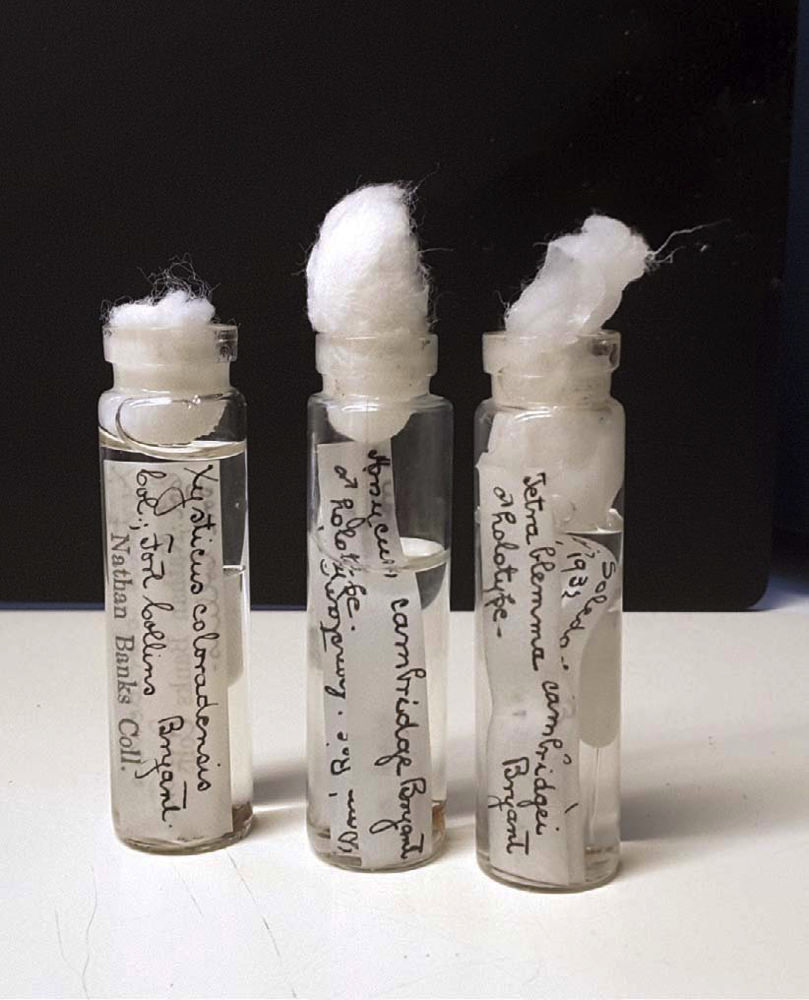

The small vials with Bryant’s handwritten labels contain type specimens she collected.

Image courtesy of the Museum of Comparative Zoology/Harvard University

She also spent countless hours labeling specimens and developing extensive catalogs of spiders from around the world, making do for decades (her thrift was famous) with a modified car headlight and faulty microscope for her taxonomic research. Even without proper equipment, she gained an international reputation. Her published MCZ catalog described spiders from Jamaica, Puerto Rico, and her native New England—she donated her own collections to the museum, including specimens caught in Vermont and New Hampshire.

The Amycus cambridgei specimen, a member of the Salticidae family (jumping spiders), is one of many identified by Bryant.

Image courtesy of the Museum of Comparative Zoology/Harvard University

Bryant’s interest in spiders began early. Her well-off Boston parents let her join field expeditions to the mountains and coasts to collect rocks, plants, and insects, spurred by a popular nature-study educational movement emphasizing object-based and outdoor learning. She attended Radcliffe for three years, taking courses with Harvard zoologists Edward Laurens Mark, Charles Davenport, and George Howard Parker, but never completed her degree after her father’s death.

Instead, she pursued a scientific career on the margins of the professional scientific community by volunteering at the MCZ. In 1898, she joined several other women who worked as museum assistants, also sorting and classifying collections, writing labels, and producing illustrations for publications. The others were paid (though far less than their male colleagues), but Bryant remained a volunteer for decades. She began receiving a small salary only in the 1930s—when she became assistant curator of spiders—and despite her official retirement in 1950, continued to work at the museum until her death. Though her name appeared only occasionally in official museum publications, her career there spanned more than five decades.

To museum colleagues, Bryant appeared alternately as a “lonely spinster” devoted to her spiders and a supportive mentor familiar with the institution. Some referred to her not unkindly as “Queen Victoria,” reflecting her age, manners, and Brahmin background. Though much of her work was solitary, she enjoyed a close friendship with Elisabeth Deichmann, Ph.D. ’27, a curator of invertebrates, and actively mentored Radcliffe students; in 1947, Radcliffe’s Phi Beta Kappa chapter elected her an honorary member. She also supported young women interested in scientific careers through Sigma Xi, the honor society for science and engineering, while her shrewd personal investments yielded generous bequests in time for the MCZ and Radcliffe.

Throughout her career, Bryant developed an extraordinary network of collectors, students, and professors around the world. Writing to beginner collectors, she offered suggestions about locating spiders; with senior professors, she exchanged specimens and corrected their classification errors. Sometimes an initial query led to a decades-long friendship and collaboration. With fellow arachnologists Harriet Frizell and Sarah Jones, Bryant often dropped her usual reserve to share gossip and advice. She offered notes of encouragement, for example, when Jones embarked on an academic teaching career, reminding her, “Do not forget that students are not all worry. So often they are an inspiration and nothing generally speaking is more helpful in clarifying one’s own ideas than in helping others.”

Just days before her death, her frequent collaborator Arthur Chickering (who succeeded her as a research associate in arachnology) sent her a note of appreciation for her support. “It is my conviction,” he wrote, “that your devotion to your studies and your curatorial work in M.C.Z. will long be regarded as a model and an inspiration to all of us who have come under your influence in any way. One does not have to be a teacher in a formal sense in order to teach great lessons. My life has been made richer through my contacts with you and…I have been inspired by your orderliness and precise habits of thought.”

Bryant’s career is just one example of the significant but largely unheralded work done by women in natural-history collections throughout the first half of the twentieth century, when faculty and curatorial positions were rarely made available to them. Nonetheless, their expertise had long-lasting results. Bryant’s “every day” work can be seen in her legacy—a world-class spider collection that remains valuable to students and researchers today.