Mapmaking, especially before the Enlightenment, had as much to do with imagination as with scientific fact. Renaissance cartographers depicted strange, quasi-mythological creatures in the far reaches of the ocean. Imposing megafauna trod across early colonial-era maps of Africa and Asia, enticing explorers to exploit their natural resources.

Detail from map above

One such map, a 1598 rendition of Iceland by Flemish cartographer Abraham Ortelius (at top), depicts the island flanked at lower left by ominous sea monsters, including a hairy sea hog and an uncanny pig-snouted, wolf-pawed fish, with a pair of blow spouts for ears. Two sea cows—not manatees, but four-legged bovines—emerge from the water. These creatures were believed to come out of the sea and feed on land, according to a text written for “Embellishing the Map: How Cartographers Confronted Empty Spaces,” a past exhibition at the Harvard Map Collection. “Scandinavia was a relatively unknown, or certainly an exotic, part of the world for most people,” explains Jonathan Rosenwasser, a cartographic reference assistant at the collection. The whales in these maps don’t look half bad, he adds, except for the strange curly tails. Northeast of Iceland, Ortelius sketched the more familiar scene shown in the detail: a mass of polar bears clambering across blocks of ice.

Image courtesy of the Harvard Map Collection

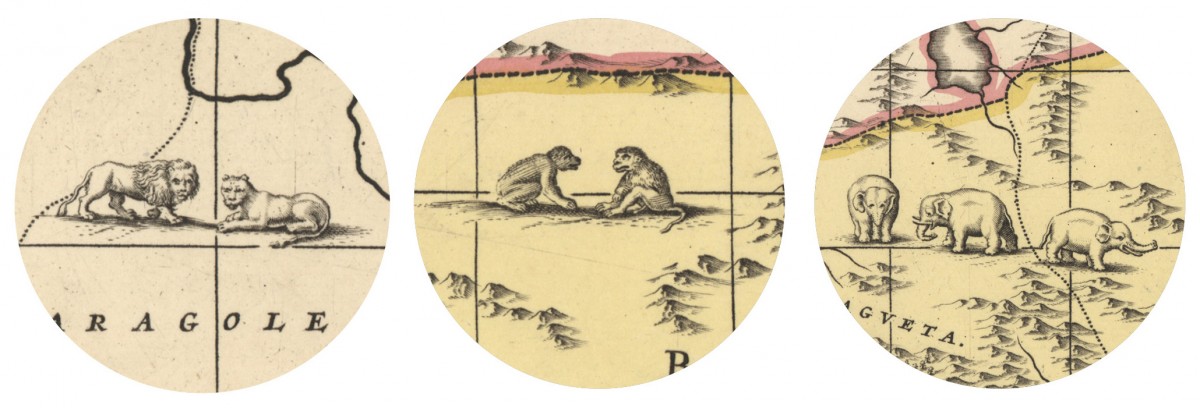

Colonial-era maps of Africa may bring to mind Jonathan Swift’s oft-quoted (though widely misinterpreted) assertion in “On Poetry: A Rapsody” that “Geographers in Afric-Maps…Place Elephants for want of Towns.” Along with lions and various types of monkeys, stately elephants populate one 1708 map of Africa’s Gold Coast (above), signaling the abundance of these animals that were widely killed for ivory; in the bottom left margin, two cherubs swim by carrying a huge tusk. “That clearly was trying to act as incentive for Europeans to look upon this land as a very fruitful area for colonizing and exploiting,” Rosenwasser says. Attractive maps like these, bulky and not particularly useful for navigation, would have been collected by universities, churches, and people with money.

During the Enlightenment, he explains, the practice of filling undocumented land with exotic creatures gave way to more modern techniques. Previously, viewers were drawn in by embellished, densely plotted maps; now the empty, uncharted spaces invited the curiosity of would-be explorers and speculators. “What now is presented on the map,” Rosenwasser writes, “reflects the science of cartography and measurement reigning supreme, not alas (as seen in the 1541 map ‘Tabula noua partis Africae’), a King riding a bridled Sea Carp!”