Amid a pandemic and a national reckoning with continuing racial injustices, the Harvard community carried on through a unique academic year, closing with a week of online class days, degree conferrals, and more. Two of the musical interludes and all three of the student speakers at this morning’s online degree ceremony reflected these tectonic disruptions—including one who drew soberly on the memory of the enslaved people from the University’s past whom Harvard began to acknowledge in 2016. And the distinguished guest speaker powerfully drove those themes home, drawing on experiences from growing up “on a constant Jim Crow diet” to presiding today at a university whose campus was once a plantation where 400 humans were held in slavery, before calling on the new graduates to serve “the mighty cause of justice.”

This dispatch summarizes the events of the week leading up to this morning’s virtual University celebration, before covering the graduation exercise in full. The texts of speakers’ remarks appear at the separate links shown in the sidebar at the top of this report.

Virtual, Again

As the coronavirus destroyed millions of lives and livelihoods, it also inevitably, if far less consequentially, disrupted the routines of individuals and institutions worldwide, Harvard among them. In March 2020, in-person teaching quickly evaporated, to be replaced by the swiftly all-too-familiar Zoom version. The intended late-May 369th Commencement crush centered on Tercentenary Theatre was quickly reduced to an online version, “Honoring the Harvard Class of 2020”—a credible, if necessarily boiled-down, rendition of the community’s favorite tradition. The 2020-2021 academic year proceeded under strict health precautions and largely in absentia: about one-quarter of undergraduates were in residence (studying exclusively online until some small experiments in hybrid learning were staged in April); only the business and medical schools managed meaningful in-person instruction for part of the year. Given the dreadful pandemic casualties of late winter, and the global dispersal of students, no suspense surrounded President Lawrence S. Bacow’s inevitable February announcement that the 2021 graduation hoopla would again be an online program (with a promise to the COVID-19 classes of 2020 and 2021 that they would, eventually, have the real thing: a Commencement on campus, presumably in May 2022).

That said, with the benefit of lessons learned last May, and a good deal more time to prepare this spring, the Commencement Office, Office for the Arts, the schools, and their vast virtual networks have managed to up their game on students’ behalf. (They may even have enjoyed not worrying about the fickle New England weather or deploying all those folding chairs and gigantic video monitors in Tercentenary Theatre, but none would openly cop to any of that. For the record, following a thunderstorm Wednesday evening, Thursday morning was clear, breezy, and a clement 76 degrees as the berobed throngs would have assembled in the dappled sunlight for a normal Commencement; hold that thought for May 26, 2022.) Thus, the storied Baccalaureate for undergraduates returned, there were class days aplenty with interesting guest speakers, still more guests are scheduled to add wattage to schools’ degree-conferrals this afternoon (check back for coverage), and a version of the Harvard Alumni Association’s annual meeting is on tap (on June 4), surrounded by reunions and featuring Bacow and yet another illustrious guest speaker. The slimmed-down, streaming Commencement/reunions week threatens to burgeon into something even more outsized.

Graduation ceremonies have proliferated, too. Prior to the main “Honoring the Harvard Class of 2021” program substituting for the full-dress Morning Exercises today, four smaller celebrations took place: an inaugural First-Gen/Next-Gen gathering, on May 23 (for all students “who are first-generation as well as lower-income, undocumented, Dacamented, mixed-status households, and TPS students,” per the Gazette); the inaugural University Lavender Graduation on May 24 (celebrating LGBTQIA+ graduates); and the Black and LatinX events that bracketed the Baccalaureate on May 25.

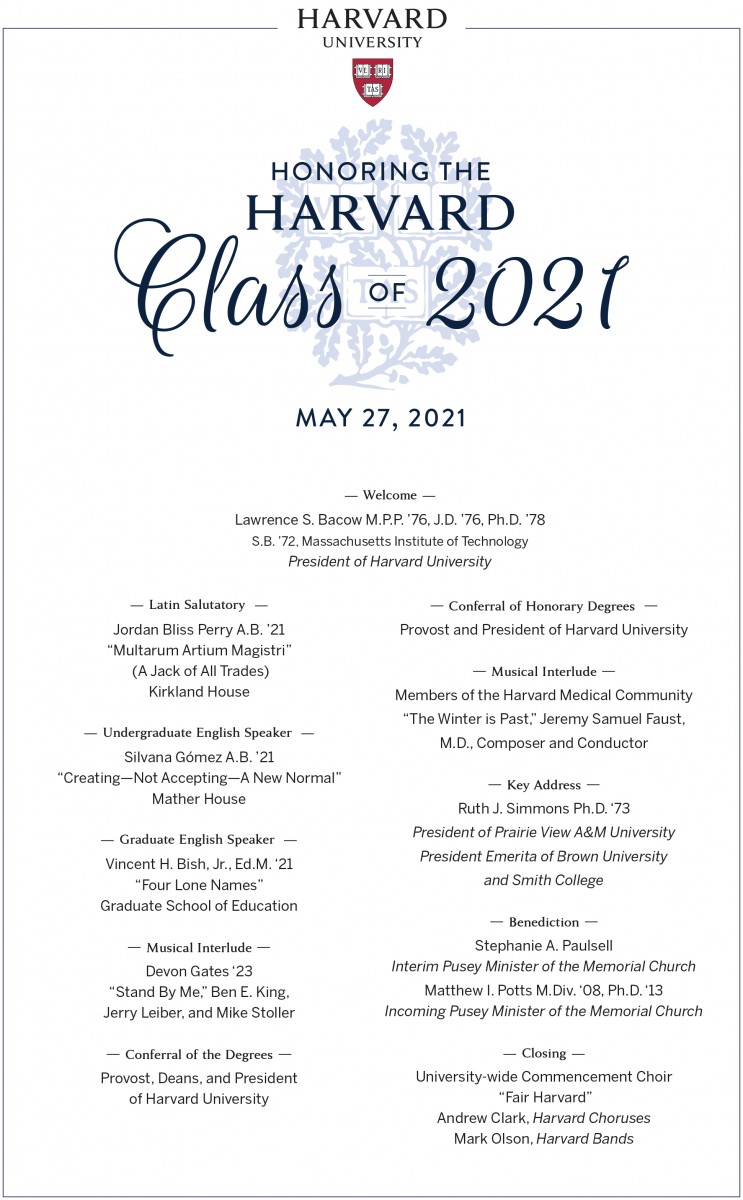

Harvard Commencement Program, May 27, 2021

The extra lead time also enabled tweaks to this morning’s online events themselves. Although this year’s program largely followed the 2020 outline—Bacow welcome, student speakers, musical interlude, conferral of degrees, musical interlude number two, guest speaker’s address, benediction, “Fair Harvard” choral closing—there were significant enhancements:

• The Latin Salutatory, skipped last year, was back, making for all three traditional student parts (see complete account below), up from two.

• Honorary degrees were conferred—on a cohort including a Nobel Prize-winning chemist, a global pioneer in online education, a distinguished journalist, and a distinguished lawyer/jurist, and more (see details below). With very few exceptions, Harvard has famously declined to award this honor to anyone who cannot show up to collect it. But with traditions already so upended (and video and streaming technologies so advanced), folding the conferrals into the virtual ceremony seemed an acceptable accommodation, given the limbo between in-person and in-absentia that much of humanity has found itself in since early last year.

• And with the Memorial Church—another very traditional part of Harvard, and the longtime backdrop for the day’s events—itself in transition, the benediction featured not one Pusey Minister but two: the interim, and her newly named regular successor. Under the circumstances, doubling up on divine assistance was surely warranted.

Honor Rolls

The Phi Beta Kappa Literary Exercises, which usually begin the week’s festivities on an intellectual and artistic note, were missing once again. But, sweetly, and in a nod to the scholarship at the heart of the enterprise, the annual PBK teaching awards—based on nominations from the academically distinguished undergraduates themselves—were conferred on:

Ali Asani, Albertson professor of Middle Eastern studies and professor of Indo-Muslim and Islamic religion and cultures;

Manja Klemenčič, lecturer in General Education in the department of sociology; and

Logan McCarty, director of science education (who played a lead role in effecting remote learning for science courses), and lecturer on physics and on chemistry and chemical biology.

In keeping with other customary rites of recognition, the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences awarded its Centennial Medal, which honors leading alumni contributors to knowledge and society, to:

Lotte Bailyn, Ph.D. ’56, social psychology;

John Hutchinson, Ph.D.’63, mechanical engineering;

Marvin Kalb, A.M. ’53, regional studies–USSR; and

Peggy McIntosh ’56, Ph.D. ’67, English and American literature and language.

Read more about the honorands here.

And the Harvard Medalists (who will be hailed during the June 4 HAA meeting, for their service to the University) were also announced:

Walter K. Clair ’77, M.D. ’81, M.P.H.’85;

Nancy-Beth Gordon Sheerr ’71; and

Preston N. Williams, Ph.D. ’67.

Toward Conferring Degrees

People who tuned in at 10:30 a.m. today for the online Morning Exercises (see the program above) were entertained by a celebratory slide show documenting campus life from 2017 (when the College class of 2021 appeared—in person, imagine that!) forward (with face masks appearing in early 2020), accompanied by a rousing Harvard University Band soundtrack.

The online ceremony proper began at 10:45 a.m. A medley of students from around the world described how they had spent the year—studying from home, loving pets, making “a tremendous amount of pasta,” mastering the cello, completing theses, taking the MCAT, being commissioned in the Army, working on the presidential campaign—and culminating in graduating from Harvard.

The sheriff of Middlesex County made a filmed appearance on the Memorial Church platform, declaring the proceedings in order—minus the cheers of the 32,000 people who were not in attendance.

And then, following the ringing of bells, President Bacow, appearing at a lectern outside his office at Massachusetts Hall ("where I haven’t been for 440 days—and counting”), reflected on the past year as “a testament to the strength and resilience of Harvard and its people,” dating to its origins before the founding of the United States—more or less before those about to graduate could ever dream of doing so. Invoking the alma mater, with the ages past and waiting before, he said, “puts the vexing present into a more welcome context.” Looking ahead, Bacow continued, “We shall overcome together.” As he has throughout the year, he said that he had "never been prouder of this institution” and its people than during these pandemic months—and he joked about a ceremony with no scrambling for Commencement tickets or parking spaces, or anxious glances at the sky.

Lawrence S. Bacow

Screenshot by Harvard Magazine

As graduates-to-be gathered with their families, he asked them to “delight in the company of those who cheered you up and cheered you on”—many of whom had been together as “unexpected suitemates” during a year of very distanced learning, from home. After a pause to thank family members and other supporters, he hailed the students’ “colossal feat,” and extended the hope that their destinies, “like our beloved University’s, be onward and bright.”

Then it was the student speakers’ turn to shine.

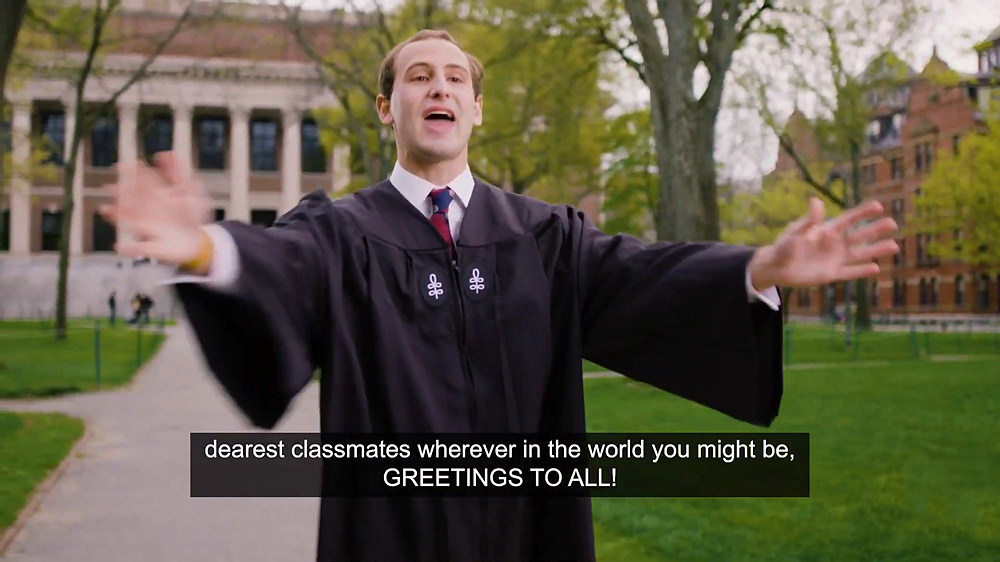

Jordan Bliss Perry ’21, Latin Salutatory: “Multarum Artium Magistri” (“A Jack of All Trades”)

Jordan Bliss Perry ’21 is glad to be bringing back the traditional Latin oration after it was omitted from last year’s programming—even if, as he noted in his speech, “this annus horribilis dictates a few changes to our ceremony.” Speaking solo from Tercentenary Theatre, with Widener Library rather than Memorial Church in the background (and with the Latin helpfully translated into English captions on screen, as it is not in person), he said:

You now behold the Tercentenary Theater not adorned with festive banners as usual, but empty through a pixelated lens. You sit not amidst a sea of thousands of comrades but in the boxed grid of a virtual meeting room. No longer do you hear the echoes of the Memorial Church bells, but rather, in their place, muted chimes from your computer.

Born in Manhattan, Perry began studying Latin in the sixth grade. He liked both sides of learning the language—the cultural, historical aspect, and the more analytical writings and translations. “Latin’s like putting a puzzle together,” he says. He enjoyed it so much that he learned Ancient Greek, too. (If Harvard had an Ancient Greek orator, as it did long ago, Perry might have opted for that dead language instead.)

Jordan Perry Bliss

Screenshot by Harvard Magazine

A resident of Kirkland House, Perry arrived at Harvard knowing he wanted to study classics, but fell in love with computer science while taking CS50 his freshman fall. “At first I was thinking, how do I make this work?” he says. “These are just two very different things.” Fortunately, he met Grove professor of the classics Mark Schiefsky, who uses programming to analyze ancient texts. Years later, he advised Perry’s senior thesis for his joint concentration in classics and computer science, which analyzed the Seventh Letter of Plato, a long, autobiographical work that some experts argued was not written entirely by Plato himself. Using artificial intelligence to compare the text to Plato’s other writings, Perry found that two sections were likely not authentic.

In his address, “Jack of All Trades,” Perry urged his classmates to continue pursuing the interdisciplinary interests they developed at Harvard—however disparate they might seem. “In our modern world, there’s always a need for a master of all trades,” he concluded. “With that in mind, may each of us be guided by our true passions, whatever they may be—may the doctors among us find their inner philosophers, the lawyers their poets, and the engineers their classicists.”

Silvana Gómez ’21, Undergraduate English Speaker: “Creating—Not Accepting—A New Normal”

Undergraduate orator Silvana Gómez ’21, backed by Memorial Church, began her speech with a reference to another monumental moment in her life: her first day of kindergarten. As she glimpsed the other children in her class eating breakfast and claiming cubbies, her mother offered some prescient words: Este es el comienzo de tu nueva experiencia (This is the beginning of a new experience). The statement resonated with the five-year-old Gómez. “Before she could take another step towards the door, I was at my mother’s feet.…The thought of having to confront this new world on my own was terrifying.”

Silvana Gómez

Screenshot by Harvard Magazine

Gómez, born in North Bergen, New Jersey, to Colombian immigrants, arrived at Harvard knowing she wanted to become a lawyer but unsure of what she’d study at the College. Her freshman-year roommate (and best friend) still teases her about all the introductory courses she took in her first two semesters. She eventually found a home in psychology, and was especially fascinated by abnormal psychology and its treatment within the criminal-justice system. The Mather House resident graduates with a concentration in psychology and a secondary in studies of women, gender, and sexuality. A member of several cultural groups on campus, she served as president of pan-Latinx organization Fuerza Latina as a junior.

Her speech, “Creating—Not Accepting—Our New Normal,” challenged her classmates to push for societal changes as the pandemic fades—an argument that extends past sickness and deaths caused by the disease itself:

We have watched as a failed health-care system has compromised the lives of those who are a part of unhoused communities, undocumented communities, low-income communities, and every other human being who has been denied equal access to health care during this time of crisis. We’ve been witness to the murders of Black people by those sworn to protect them—murders that have been normalized and justified for generations. We’ve witnessed the murders of Asian Americans as a result of xenophobia perpetuated by divisive political leadership spewing hateful and dangerous rhetoric.

“And while we may want to wrap our arms around the familiarity of our dining halls, our Houses, and each other,” she continued, “it is our time to go out into the world and build something that we are proud of.” Those who approach their next stages in life with some fears can follow some more advice from Gómez’s mother: No importa lo asustada que te sientas en el momento, siempre superas tus miedos y sigues adelante (No matter how scared you are in the moment, you overcome your fears and keep pushing).

Vincent H. Bish Jr., Ed.M. ’21, Graduate English Speaker: “Four Lone Names”

In his stem-winding, Preacherly speech, graduate orator Vincent H. Bish Jr. reflected on a plaque that can easily be missed in the bustle of Harvard life (it appeared behind him, as he gave his address from Wadsworth House).

Every time I walk through Wadsworth Gate—and see the plaque of those four lone enslaved that lived here, at Harvard—I am gobsmacked. I am thunderstruck at the responsibility of what it means to be a scion of that living. Of that horror. Of that opportunity to make them proud. I wipe their names clean with my fingers because they are my entry-point to this place. And I honor them: as forefathers, foremothers, forebears that helped to—from the sordid debris of our collective history—establish this magical place. But as I face them—there on the wall—I am without words.

Bish was born in Hartford, Connecticut, to parents from St. Catherine, Jamaica. He went to high school at St. Paul’s in New Hampshire before attending Trinity College, where he double-majored in English and public policy and law. Not one to stick to a single field, he has pursued diverse positions in his postgraduate life. In 2015 and 2016, he served as a junior analyst and assistant letter writer in the Obama administration, helping decide which 10 letters made their way to the president’s desk each day. Later, he worked as an operations director at the technology company Slack, running an initiative that trained prisoners in coding and helped them find work after leaving prison.

Vincent H. Bish speaking at Wadsworth House, with the tablet naming slaves owned by Harvard presidents over his right shoulder in the background

Screenshot by Harvard Magazine

An idealist, Bish thinks that many of the intractable problems discussed today are not as unsolvable as they seem. “I think they seem unsolvable because we’re looking at them through our siloed perspectives,” he says. He compares his education and experiences in business, education, and government to the many lenses of an X-ray machine, working together to produce an image that would otherwise be unattainable. Now his master’s—in the Graduate School of Education’s technology, innovation, and education track—will give him another lens.

Bish called on his fellow graduates to use their experiences and future careers to honor the memories of the enslaved people whose names are inscribed within Harvard’s gates: Bilhah, Venus, Titus, and Juba. “Live lives worthy of their service,” he said. “Live lives that make right the sin of their bondage.”

Finding Courage in Dark Times: “Stand by Me”

The first musical interlude, “Stand by Me,” introduced by Provost Alan Garber, was performed by Devon Gates ’23, a vocalist and bassist born in Atlanta and now dually enrolled at Berklee College of Music. The future Winthrop House resident recorded the classic Ben E. King song alone in Sanders Theatre, accompanyiing herself on her bass, with producers and camera operators providing feedback and recording her remotely. Gates, who hadn’t performed in the hall since November of 2019, was thankful for the opportunity—and doubts she’ll ever get to perform alone in the gorgeous, resonant hall again. “It has a presence of its own that can kind of swallow you,” she said, “which is really something I hadn’t experienced in a while.”

Devon Gates

Screenshot by Harvard Magazine

For Gates, an improviser, each take was a bit different. “I thought it was really important to keep aspects of spontaneity,” she said. “Am I going to take a little instrumental break here—let the song breathe a little bit—or am I going to keep going straight ahead?”

But the lyrics remained unchanged. Gates thought the words from the original song fit well with the tone of the ceremony and the year everyone has experienced. “I like that you’re asking someone to stand by you, and you’re telling them to stand by you,” she said. “There’s not necessarily an understanding that everyone is already doing that. So I like that it asks something of a listener.” She said it was particularly meaningful that the song was written by a black American artist. The song itself is based on a spiritual written by soul artists Sam Cooke and J.W. Alexander, who derived inspiration from Psalm 46. In a pandemic year, King’s lyrics felt especially fitting:

If the sky that we look upon

Should tumble and fall

Or the mountains should crumble to the sea

I won't cry, I won't cry

No, I won't shed a tear

Just as long as you stand, stand by me

The Main Event: Conferring Degrees…

The Harvard Crimson’s Commencement issue and senior survey, released this morning, showed, unsurprisingly, that the College graduates were dismayed they could not have an in-person Commencement (84 percent of respondents said they viewed the online program unfavorably). But, as usual, those joining the workforce again head off to lucrative first jobs—and as of midday are, in fact, now possessors of Harvard degrees: not a bad thing under the calamitous world circumstances of the past 15 months. A little perspective, folks.

President Bacow, lower left, and the deans applaud the new graduates, whose degrees were conferred in record time.

Screenshot by Harvard Magazine

The conferral itself was record-setting for its brevity. Garber introduced the deans, who seriatim—in gowns, beside their buildings—introduced the accomplished students in this order: Graduate School of Arts and Sciences, engineering and applied sciences, extension and continuing education, dental, medical, divinity, law, business, design, public health, education, and College (Faculty of Arts and Sciences dean Claudine Gay and College dean Rakesh Khurana combining to present “the remarkable and resilient class of 2021”).

In a single sweeping statement, Bacow conferred degrees on all, and the deed was done, in under three minutes flat, with applause from the president and deans.

…and Honorary Degrees

President Bacow at his lectern and Garber in the Yard—complemented by video presentations on the honorands’ lives and works—finally got the goods to last year’s guest speaker, news editor Martin (Marty) Baron, who would ordinarily have received a degree on the day he delivered his address. (Making it a two-fer week, Baron was the speaker at Suffolk University’s graduation, May 22 at Fenway Park, and collected an honorary degree there, too.)

The class of 2020/21 honorands, additionally distinguished by the unique means of conferral (and accompanied by the citations), comprises:

Frances H. Arnold, Linus Pauling professor of chemical engineering, bioengineering, and biochemistry, California Institute of Technology, co-winner of the 2018 Nobel Prize in Chemistry, Doctor of Science:

Evolving enzymes with neoteric techniques,

enabling applications in farming, fuels, and pharma,

an adroit doyenne of designer proteins

who makes it easier being green.

Marty Baron, past executive editor, The Washington Post, and former news executive at The Boston Globe, The New York Times, the Los Angeles Times, and The Miami Herald, Doctor of Laws:

A formidable fiduciary of America’s fourth estate;

as a herald of light and a bearer of truth,

he has deftly kept us posted

on the times around the globe.

Arlie R. Hochschild, professor of sociology emerita at the University of California, Berkeley, widely known for her research on the connections between emotions and social life, in the context of work and family—and most recently, in the context of political disaffection and the rise of the Tea Party, Doctor of Laws:

Crossing chasms in outlook with empathy her springboard,

probing the interplay of feelings and relations,

she has reckoned the wages of emotional labor

and sought to discern where the right sees wrongs.

Salman Amin Khan, M.B.A. ’03, founder of the nonprofit Khan Academy, the global, self-paced, online learning nonprofit, Doctor of Laws:

An avid avatar of active learning

who kindles curiosity in countless students;

a virtual virtuoso whose salmagundi of videos

opens pedagogic pathways for people worldwide.

Margaret H. Marshall, Ed.M. ’69, Ed ’77, L ’78, a student leader against apartheid in South Africa, her native land, and a lawyer who held positions of leadership in higher education—and as chief justice of the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court, where she wrote the majority opinion in Goodridge v. Department of Public Health, which held that Massachusetts could not deny same-sex couples the right to marry. Doctor of Laws:

An ardent advocate against apartheid;

an eminent exponent of equality under law;

in serving venerable institutions, a venerated leader;

in striving for justice, a chief marshal supreme.

Sebastião Salgado, the Brazilian-born photographer and photo documentarían who has made visible the conditions under which workers in less developed nations toil—mining gold by hand, breaking down ships, fighting oil well fires—and has recently turned to conservation and humans’ relationship to nature. Doctor of Arts:

With sublime images of poignant power,

with profound devotion to human dignity,

with concern for the precarity of a fragile planet,

he frames spellbinding stories of life on Earth.

Anna Deavere Smith, the dramatist and actress, widely known for performances in the theater, movies, and television series such as The West Wing and Nurse Jackie, has played an especially important role in documenting American lives and character through original dramas blending theater and journalism and performed in the one-woman shows Fires in the Mirror and Twilight: Los Angeles, among others. Doctor of Arts:

Stirring our conscience with artful acumen,

a portraitist whose palette evokes many hues and shades;

immersing herself in the lives of others,

she holds up a mirror to what fires human nature.

A COVID Chorus: “The Winter Is Past”

The second musical interlude responded to the pandemic in a different way: a passage from darkness toward hope, composed, conducted, and performed by members of the extended Harvard Medical community (nine singers and a cellist): physicians, researchers, nurses who were on the front lines of delivering care at the height of the crisis, before the promise of effective vaccines became a reality—scenes made vivid in the medley of photos interspersed with the recording of the performers.

When Jeremy S. Faust was asked to put together a short choral performance for Harvard’s graduation ceremonies, he tried to think of a song that would perfectly fit the occasion. When he couldn’t, he composed one himself. The result is “The Winter Is Past,” a choral number featuring members of Harvard’s medical and science community, performed outside of the Medical School’s Gordon Hall.

The choir performs with cello soloist Camden Archambeau '23.

The choir performs with cello soloist Camden Archambeau '23.

Screenshot by Harvard Magazine

Faust is an attending physician in the Brigham and Women’s Hospital Department of Emergency Medicine and instructor at the Medical School, but he studied music composition at Williams College and received a master’s degree in music theory and composition at the University of California, Davis. Though he normally conducts the Longwood Chorus—made up almost entirely of scientists and clinicians—the pandemic put a stop to any rehearsals. “I really just became a very one-dimensional person,” Faust said. As the pandemic worsened and public health faltered, all his energy went into his hospital work and COVID-19 research. “And I just shut everything out, including music, including the arts. I didn’t even listen to music.”

Faust’s aspiration was to write something that could meet the unusual moment—reflecting on how many have felt during the pandemic, but allowing for hope that those days are largely in the past. “We want to confront the moment without undermining or brushing aside just how long we’ve been in that tunnel,” he said, “and how hard it’s been.” His text, based on Song of Solomon from the Hebrew Bible, is :

For behold, the winter is past;

the rain is over and gone.

The flowers appear upon the earth,

the time of the singing has come.

Ruth J. Simmons, “It is never too late to do justice”

The guest speaker, Ruth J. Simmons, Ph.D. ’73, LL.D. ’02—president emerita of Smith College and Brown University, now president of Prairie View A&M—earned her Harvard doctorate the regular way, and collected an honorary one previously, so she didn’t receive one today. (Her 2002 citation read, “Opening minds, opening doors, opening eyes to new opportunities, she has spurred higher education higher with inspiring providence.”) Bacow introduced her as “a powerful and passionate advocate for education.”

Her address, titled “A Time for Justice—A Time for Commitment,” began on a personal note, scrolling backward from her mild trepidation about giving such a speech on such an occasion to her earlier self: “Growing up on a constant Jim Crow diet that offered assertions of my inferiority, I’m always that same little black girl trying to believe in and demonstrate her worthiness.” Speaking from Prairie View—at a Harvard-decorated lectern, and in her Crimson doctoral gown—and informally on behalf of “the Historically Black and Minority Serving [often known as Historically Black Colleges and Universities, HBCUs] institutions that have the weight and privilege of advancing access, equity and opportunity for so many communities across our world,” she observed that such schools were founded at the end of Reconstruction, “when blacks were thought to be unable to perform the highest level academic study.” Her own campus, in fact, had been the site of Alta Vista Plantation, where “400 human beings were held in slavery” before the land was sold to the state of Texas. “Thus, our very steps, as they daily tread upon vestiges of the suffering of our ancestors, call to us constantly to do our full duty as citizens.” In pursuit of that duty, Prairie View and peer institutions

… designed with limited resources, served the state and nation by admitting students to whom full access to the fruits of liberty was intentionally blocked. We are therefore proud of our legacy of endurance and even prouder of the fact that we converted an assertion of the inferiority of African Americans into a triumph of human capacity. Like other HBCUs, we made a place to empower rather than disparage, to open minds rather than imprison them, to create pathways to promise rather than to stifle opportunity.

And that is the work of every “true university,” Simmons continued.

When she arrived at Harvard, she recalled, the product of a segregated upbringing in Houston and study at an HBCU, “I am ashamed to say that in my youth, I secretly bought into the prevailing racial assumptions of the day: that someone like me would be ill-prepared to benefit from and contribute to study at a university of Harvard’s stature.” Encountering the University’s traditions,

My reaction was very much akin to the French expression denoting window shopping: “lécher les vitrines.” Those of us who are outsiders are often as mere observers looking through windows, salivating and wondering how we might ever be able to attain a sense of inclusion, acceptance and respect. Just as when, as a child, I was banned from white establishments, I identified as the outsider looking enviously at others who not only had full access to Harvard’s history and traditions but who also could so easily see themselves reflected in them. Few things that I could see at Harvard at the time represented me. Perhaps it is the memory of that feeling that moved me to remain in university life to make that experience easier for others who felt excluded.

From such experiences,

I understood that to change our country, we had to insist that everyone’s humanity, everyone’s traditions and history, everyone’s identity contributes to our learning about the world we must live in together. I came to believe what Harvard expressed in its admission philosophy: that such human differences, intentionally engaged in the educational context, are as much a resource to our intellectual growth as the magnificent tomes that we build libraries to protect and the state of the art equipment proudly arrayed in our laboratories. The encounter with difference rocks!

Such encounters, she continued, are the work of a lifetime. In terms of universities’ work, that means not merely testing “brilliant minds” but “guid[ing] them toward enlightenment, enabling thereby the most fruitful and holistic use of their students’ intelligence and humanity.” That in turn means helping students attain self-knowledge, but also “helping them judge others fairly, using the full measure of their empathy and intelligence to do so.” At the current moment of “irrational hatred of targeted groups,” Simmons said,

What stands between such malefactors and the destruction of our common purpose are people like you who, having experienced learning through difference, courageously stand up for the rights of those who are targeted. Your Harvard education, if you were paying close attention here, should have encouraged you to commit willingly to playing such a role. If you follow through on this commitment, in addition to anything else you accomplish in life, you will be saving lives, stanching the flow of hatred and the dissolution of our national bond. You will be serving the mighty cause of justice.

Mighty Harvard itself has such a role to play, she underlined, using “its immense stature to address the widening gaps in how different groups experience freedom and justice. I spoke earlier about the heroic work of HBCUs and minority-serving institutions that keep our country open and advancing the cause of equality and access. Yet, many of them have been starved for much of their history by the legacy of underfunding and isolation from the mainstream of higher education.” She called on universities like this one to acknowledge the constraints under which the HBCUs labor, even as places like Harvard “had the wind at their back, flourishing from endowments, strong enrollments, constant curricular expansion, massive infrastructure improvements, and significant endowment growth” while the HBCUs “often had gale force winds impeding their development.” It is time for Harvard, she maintained, “to add to its luster” by standing alongside minority-serving institutions as a partner, advocating for greater funding and elevating “the fight for parity and justice.”

In the same vein, she spoke passionately about the value of public schooling to prepare children for better futures (including pursuing a higher education) “[U]niversities and all of you must play a leadership role in reversing the designation of the teaching profession as less intellectually worthy, less glamorous, and less important than the high-flying careers of financiers and technologists.”

Addressing the graduates, she summoned them directly to “declare that you will not give sanction to discriminatory actions that hold some groups back to the advantage of others. I call on you to be a force for inclusion by not choosing enclaves of wealth, privilege and tribalism such that you abandon the lessons you learned from your Harvard experience of diversity. I call on you to do your part to ensure that generations to come will no longer be standing on the outside fighting for fairness, respect and inclusion.”

Today, she said, at Prairie View, “students are waging the same battles that were so hard fought when I was a teenager: safe passage in the face of bigotry, the right to vote, and equal access to educational and professional opportunities.” She mentioned Sandra Bland, a Prairie View alumna who was stopped for a minor traffic violation at the entrance to campus, jailed, and found dead in her cell three days later. [The death, ruled a suicide, resulted in investigations about the arrest and inadequate mental-health checks, a perjury indictment of the arresting state trooper, his permanent separation from law enforcement, and a $1.9-million wrongful-death settlement with Bland’s family.] “Must every generation add more tragic evidence of the racial hatred that has troubled the world?” Simmons asked. “Our work is not done as long as there are young people growing up with the thought that they matter less than others.”

Bringing her case home from the institution to the graduates who have benefited so richly from studying here, she said, “Just as I ask Harvard to use its voice on behalf of minority institutions that have been unfairly treated across time, I ask you to add your voice to the cause of justice wherever you go.” On the day when they had earned their laurels as scholars, she told the graduates, “Taking up the cause of justice, you will earn your laurels as a human being.”

At the end of her 22-minute address, Bacow thanked Simmons for her powerful “knowledge, discernment, and empathy.”

Read Simmons’s full text here, as prepared for delivery.

Over and Out

Just two things remained to close out the program: the benediction by duet, featuring Interim Pusey Minister Stephanie A. Paulsell and her successor, Matthew I. Potts, both of Harvard Divinity School.

They spoke alternately, from outside the Church. Potts lamented, “It's lonely here without you,” and Paulsell recalled not only those missing the day but “loved ones lost over the course of these difficult months.” She said Harvard Yard was never intended to be a final destination, but rather a starting point, and Potts urged the graduates to “embrace and shape the future with daring and care.” Paulsell hoped that the echoes from this place, and from the day, would “rise up in you as a fresh vision of tomorrow” (as it is about to for Memorial Church itself), and then the pair pronounced dual amens.

Interim Pusey Minister Stephanie A. Paulsell and her successor, Matthew I. Potts, both of Harvard Divinity School

Screenshot by Harvard Magazine

And then, on the template established last May, a pixelated University-wide Commencement Choir sang “Fair Harvard” in digitally manufactured unison. The singers were updated for 2021 of course—as were some of the scenic images, such as the newly completed, if not yet fully occupied, Allston home to much of the engineering and applied sciences faculty, who are eager for their students to return.

Ahead of schedule, thanks to the wonders of the digital age, the program concluded at 12:18 p.m. to the chiming of the bells—and with nary a sore back, rain-dampened gown, or overheated doting parent among those watching online, far from Tercentenary Theatre (alas).

Having thus risen “through change and through storm” virtually again (and how!), for an entire, socially distanced academic year, one might think Harvard had established a new University Commencement tradition. Community members fervently hope it will not be invoked a third time in any “age that is waiting before.”