“Stop the Steal” was first trotted out during the 2016 Republican primaries. As the Republican National Convention approached, Donald Trump’s campaign consultant Roger Stone coined the phrase, urging people to resist the allegedly corrupt “establishment” Republicans who wouldn’t let Trump win. When he prevailed, it became irrelevant. Stone brought the term back for the general election, but when Trump won again, the phrase lost steam.

But on and after Election Day 2020, as the results appeared increasingly less favorable to the incumbent president, Joan Donovan, research director at the Harvard Kennedy School’s Shorenstein Center on Media, Politics, and Public Policy, watched a constellation of what she calls “disinformers” rally around the phrase again. In 24 hours, the most prominent “Stop the Steal” Facebook group—promoted across social media by outspoken conspiracy theorists, and algorithmically recommended to likely supporters by the site itself—attracted more than 300,000 members. She saw the online movement shift to the streets, with provocateurs like Alex Jones and Ali Alexander showing up at state capitols across the country, pressing representatives not to certify the election and riling up those who believed the process to be a sham.

So when “Stop the Steal” turned violent on January 6, few were less surprised than Donovan. Hours before the Capitol was breached by protesters, she had tweeted a prediction: “Today we will witness the full break of the MAGA movement from representative politics. As you watch what unfolds in DC today, remember that activists are both inside and outside the Capitol.”

By the end of the day, four had died, including a woman shot by a Capitol Police officer as she climbed through a shattered window. (One officer assaulted with chemical spray died the next day of natural causes, according to the Washington, D.C., chief medical examiner’s office.) The Capitol Police Union reported that nearly 140 officers were injured during the attack, and two died by suicide shortly after. The damage to the Capitol has cost tens of millions of dollars to repair; more than 400 people have been charged with federal crimes.

“What we saw on January 6 was not a young people’s revolution. This was an artifact, or an outcome, of the design of Facebook,” Donovan says. “The time is now for realizing that of course, we can’t walk back in time and do something different. But we surely can insist the future of the internet isn’t like the present.”

The “Algorithmic Economy”

Misinformation is everywhere, an inherent part of communication that does not imply intent. Accidentally telling someone Independence Day falls on July 3 is misinformation. When misinformation becomes deliberate—deception on purpose—that’s disinformation.

The purpose varies. Sometimes disinformation is spread for political or financial gain—convincing constituents that a rival candidate has a sordid history, or exploiting people’s interest in a made-up scandal to increase website traffic and sell merchandise. But often the reason is less clear: vague intentions to sow discord and muddy the waters around any given subject.

For the past few years, Donovan has spent a couple hours each night listening to white-supremacist podcasts and videos. One of many scholars who are now focused on the origins and intensifying effects of disinformation, she’s found that this monitoring is one of the best ways to keep track of the country’s most prominent disinformation campaigns and blatant attempts at media manipulation. The sessions, she says, help her see a few months into the future.

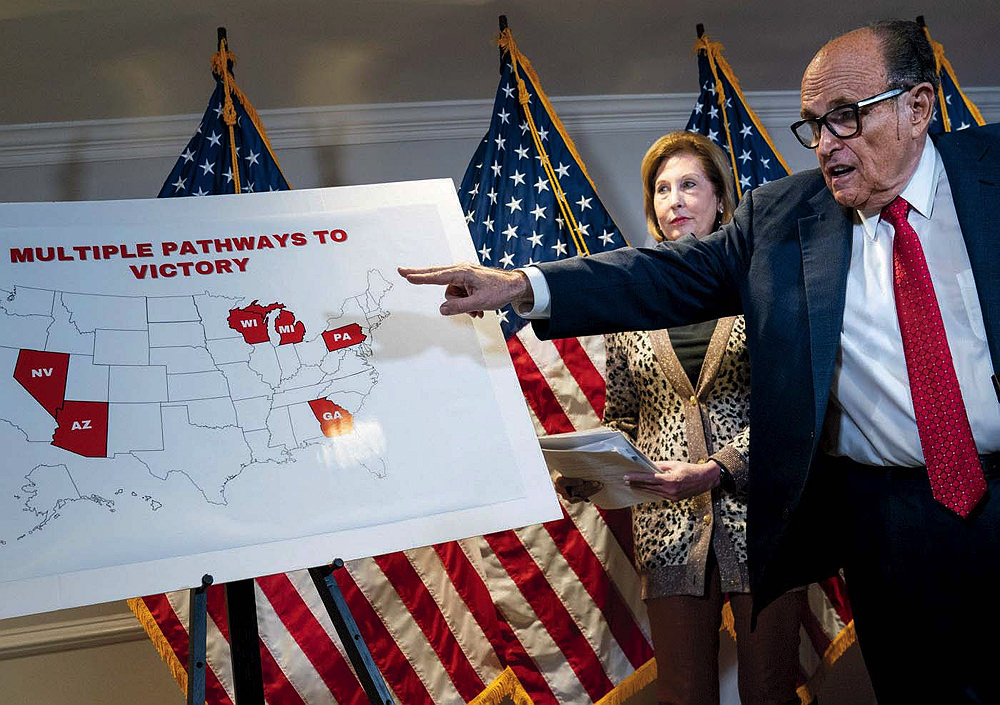

President Trump had told his followers well in advance that something big was going to happen on January 6. Even before the election took place, he primed supporters on Twitter and elsewhere to believe that a loss could be explained only by massive voter fraud. The more Donovan looked into related conspiracy theories, the more popped up on her social-media feeds. “In some instances, you have to go looking for it, it’s very specific,” she says. “But then what happens is that these algorithms will hook into it, particularly the YouTube algorithm, and they will keep trying to get you to watch more content about it.” Looking up “Giuliani” on YouTube, for example, led to an inundation of voter-fraud allegations promoted by Trump lawyer and adviser Rudolph Giuliani.

Rudy Giuliani speaks to the press in support of conspiracy theories aimed at overturning the 2020 election results. Lawyer Sidney Powell is behind him.

Photograph by Drew Angerer/Getty Images

One Giuliani favorite was the “Hammer and Scorecard” theory, a bogus claim that machines made by Dominion Voting Systems switched millions of votes from Trump to Biden. After bouncing around among far-right influencers, blogs, and social-media outlets, the theory reached the president himself. Just over a week after Election Day, he tweeted that Dominion had deleted millions of votes from his totals, flipping the election result. And then the theory was everywhere: recommended to people who liked similar content on social media, discussed by pro-Trump media like Fox News and Newsmax, and further amplified by mainstream media sources that discussed the information solely to discredit it.

Although many scholars describe the current media and economic system as an “attention economy,” Donovan disagrees. “That gives far too much agency to the user,” she says. Instead, she calls the current system an “algorithmic economy,” in which individuals have ceded control of their attention to sites like Facebook, YouTube, and Twitter. “It may be the case that you have 500 friends on Facebook,” she says, “but Facebook is going to determine in what proportion you see different people based on different user profiles.” Someone who has clicked a YouTube video about how the COVID pandemic is a hoax is unlikely to be directed toward videos touting the efficacy of the Moderna vaccine; someone who “likes” all of Speaker of the House Nancy Pelosi’s tweets isn’t steered to those of Donald Trump Jr.

It’s this algorithmic economy that Donovan believes fuels countless media-manipulation campaigns. Though influential conspiracy theories may seem to appear from nowhere, she and her team have analyzed some of the most prominent examples, parsing out where the disinformation came from, why, and how. Their analysis is bottom-up: from source, to spread, to potential mitigation.

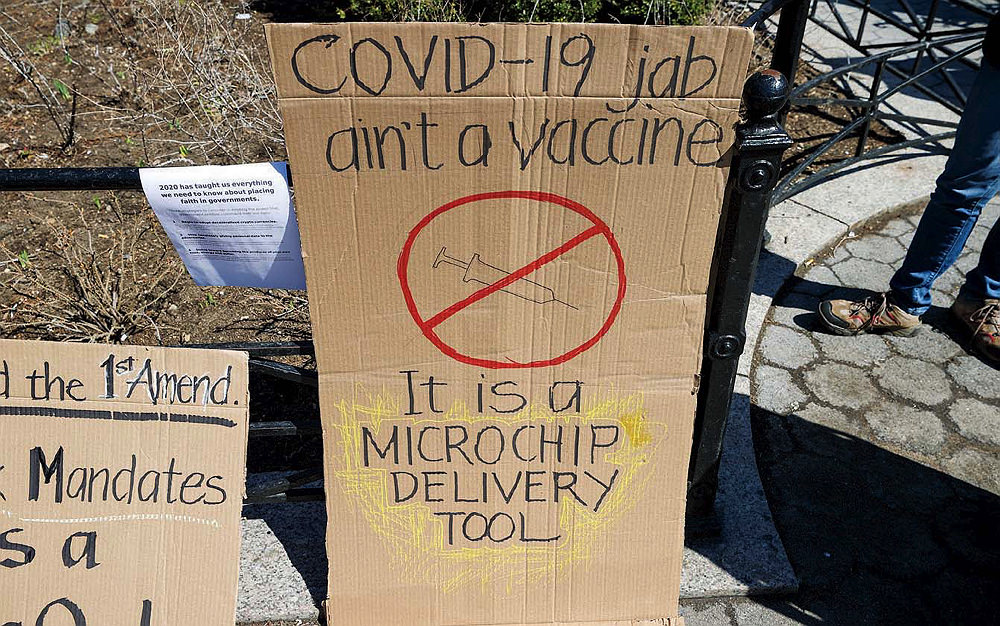

The first stage they look for is a manipulation campaign’s planning and origin, searching for signs that groups are discussing an idea that could be the center of a disinformation campaign. “The campaigns do tend to start from a spark of conversation,” Donovan says. “[It’s] somewhere where we’ve discovered a bunch of people…saying things like, ‘Wouldn’t it be great if everybody thought the upcoming vaccine had a microchip in it?’” Given the scale of the internet, Donovan and her colleagues tend to pay attention to this kind of online chatter only when it’s coming from groups that have previously seeded media-manipulation campaigns. They traced the beginning of the “Hammer and Scorecard” conspiracy to 2013, when a former intelligence contractor started spreading rumors about a deep-state supercomputer called Hammer that allowed him to hack databases and collect the information of millions of Americans. It was only in 2020, though, that the most recent iteration of the “Hammer and Scorecard” conspiracy was posted to The American Report, a self-published blog. It claimed that the same Scorecard software that allegedly helped Barack Obama steal the 2012 election was being applied anew to steal the 2020 election for his vice president, Joseph Biden.

The next stage is seeding the campaign across social platforms and the internet. That’s when the discussion transforms from a conversation among a few people on a single platform, like Facebook or message-board site 4Chan, and spreads the ideas to other online spaces. Donovan and her team traced a quote from a Twitter user, @SongBird4Trump, who warned followers on October 29 that voting machines would transfer votes to Democrats, and tagged retired general (and, briefly, Trump administration National Security Advisor) Michael Flynn, Trump-supporting lawyer Sidney Powell, three of the president’s children, and staunch pro-Trump news organizations like One America News. The theory began popping up in more popular outlets, including Steve Bannon’s podcast, The War Room. Bannon discussed “Hammer and Scorecard” with Powell, who spread the theory further.

But to Donovan, the third stage—when activists, politicians, journalists, and “industry” (companies seeking profit or a social-media boost from disinformation) begin to respond—is most important. It’s here that siloed information can break into mainstream discussions. When Lou Dobbs ’67 interviewed Powell on his Fox Business news show on November 6, she repeated the conspiracy’s central premise and introduced a spurious connection to Venezuela, spurring similar discussions on networks like One America Newsand Newsmax. Such coverage helps legitimize the conspiracy theory and provides a much wider audience, spurring more coverage, more online posts, and a more out-of-control online environment where disinformation flies unchecked. When Trump and his lawyers filed more than 60 lawsuits in an attempt to secure more electoral votes, their claims of election cheating made sense to supporters already alerted to similar allegations.

The Mass Market for Disinformation

Not all academics agree with the popular view of an internet-driven model of media-manipulation and disinformation campaigns. In 2020, Yochai Benkler, Berkman professor for entrepreneurial legal studies and faculty co-director of the Law School’s Berkman Klein Center for Internet and Society, and colleagues examined some of the most discussed stories about election fraud and traced what caused each spike in media attention. In a vast majority of cases, he found, a surge of coverage stemmed not from a social-media campaign, but rather from a mass-media story or President Trump himself. “In each case, very clearly beginning right after the first COVID relief bill, when Democrats tried to put in significant funding for mail-in voting, Trump and the GOP leadership began to release statements about voter fraud being a major issue,” Benkler says, “And then within hours to a day, social media circulates these messages.” When looking at media coverage of absentee-ballot disinformation in the 2020 election cycle, Benkler and his colleagues failed to see any coverage peaks “meaningfully driven by an online disinformation campaign.” Each one had an obvious elite-driven triggering event—a top-down narrative.

Yochai Benkler

Photograph by Jessica Scranton

“Technology is easy to blame, because you don’t have to seem political,” he says. “[Disinformation campaigns] didn’t happen on the right as opposed to on the left.…And therefore we have a neutral explanation to what happened.” The reality is quite different in Benkler’s view, driven by mass media and decades of media polarization that he traces back to the 1980s. “Starting with World War II and all the way through the end of the 1970s, you’ve got partisan media on the left and on the right, each of which is supported by primarily philanthropic efforts and user[s],” he says—like the conservative radio program Manion Forum and publications like The National Review and Human Events on the rightor Mother Jones and In These Times on the left. “What changes dramatically in the 1980s is televangelism becomes a big business,” he continues. By then, the Christian Broadcasting Network was publishing its own news and became the third-most-watched cable channel. But it was Rush Limbaugh who really re-invented the model, Benkler emphasizes: “That pushing of outrage and identity confirmation through hatred of the other…becomes big business. So there’s a big market segment that’s not getting what it wants from the mainstream media.” Fox News helped fill the gap in the 1990s, and within a decade, some studies showed that the channel’s coverage was worth a couple percentage points of additional turnout in national elections.

“If you’re trying to understand what causes tens of millions of people to believe that Democrats stole the election,” says Yochai Benkler, “that’s not coming from social media.”

When highly partisan news sites like Steve Bannon’s Breitbart appeared in 2007, 20 years had already been invested in an asymmetric system, with market dynamics on the left and right varying dramatically, Benkler continues. “[B]y the time market actors like Air America and NBC tried to go and essentially mirror talk radio and Fox for the left, the markets were not there. [Those efforts were] just not big enough and not excited enough about what they were offering.” These highly partisan market incentives produce much of the disinformation that most Americans see, he stresses—not the internet.

“If you’re trying to understand what causes tens of millions of people to believe that Democrats stole the election,” Benkler amplifies, “or that Hillary Clinton runs a pedophilia ring out of a basement of a pizza parlor, that’s not coming from social media. That’s coming from Fox News and Sirius XM Radio, Bannon and Breitbart, Rush Limbaugh and Sean Hannity on radio.” After somebody like Limbaugh supplies a steady stream of outrage, and proves it’s enormously profitable, the audience keeps looking for similar programming. “So if you’re trying to come into the market, you’re going to come in with even more salt and sugar and fat, and the sellers of kale are going to do even worse,” Benkler says. “That’s essentially what happened in right-wing media, and that’s what happened to right-wing politicians.”

How Deep the Damage?

Arguments about the source and proliferation of disinformation will continue. Donovan doesn’t believe that mass media eclipses the internet in spreading damaging conspiracies. As a sociologist, she’s more interested in examining the texture of the culture than in pointing out which branch of media is truly dominant in the process. The ways of quantifying and studying the effects of cable news and radio are more established, “but there is no study in the world that can disambiguate that people were only watching Fox News or only listening to the radio and had no contact with social media,” she says. “The fact of the matter is repetition is what’s getting people sucked into these rabbit holes.” That repetition, coupled with the responsiveness people get online, accelerates the spread of disinformation.

Disinformation has played a role in two of the country’s biggest crises this year: COVID-19 and the aftermath of the 2020 election.

Photograph by Tayfun Coskun/Anadolu Agency via Getty Images

Other experts emphasize the field’s youth, suggesting that much of what’s known about disinformation is still up for debate. Even the term “misinformation” is unstable. “Different researchers and different papers are saying, ‘I’m defining “misinformation” for this particular context,’” says Natascha Chtena, editor-in-chief of the Harvard Kennedy School’s Misinformation Review. Much of the research tailored to this current news environment has emerged since the 2016 election, and scholars who specialize in different fields can disagree strongly. It’s a new enough focus that Donovan, whose internet-focused approach began during the Occupy Wall Street Movement, is a relative veteran.

Matthew Baum, Kalb professor of global communications at the Kennedy School, is skeptical that the modern media landscape is uniquely harmful to the nation’s political climate—or that the phenomenon is understood rigorously yet. “We’ve had four years since people started really paying attention to this seriously,” he says. It will take more evidence for him to accept the common perception that disinformation is perverting politics, enhancing polarization, creating a post-truth environment, and destroying public trust and democracy.

“Misinformation, broadly defined—or even more narrowly defined if you want to talk about our fake-news environment—is by no means anything new,” Baum says, “nor is the worry that it poses a crisis for democracy.”

“Misinformation, broadly defined—or even more narrowly defined if you want to talk about our fake-news environment—is by no means anything new at all,” Baum says, “nor is the worry that it poses a crisis for democracy.” Though he believes social media make polarization worse, he doesn’t believe it created the current state of U.S. politics. “I think it’s very easy to overdramatize the role of technology and information, because every generation does it,” he says. He traces the country’s polarized state to factors that have played out for decades, like gerrymandering, a more partisan sorting of populations, and economic alienation.

Some phenomena are new, though. Social media bring to the table “a new marriage of supply and demand,” he says. “People like to be entertained. They like information that makes them feel good; they don’t like information that makes them feel bad.” Unless people have an overriding reason to overturn their own beliefs, they’re not inclined to do so. That’s true even for some of the wildest theories spouted by conspiracy-driven groups like QAnon. Baum thinks of the media’s fragmentation as gasoline: “It’s thrown on top of the fire, but it didn’t light the fire.” Though he’s not sure the current disinformation environment is the worst it’s ever been, he still believes it has created problems that need to be solved. “If Donald Trump hadn’t been pushing a rigged election,” he clarifies, “I’m pretty sure there would have been no insurrection.”

Toward a Public-Interest Internet

When David Rand, Ph.D. ’09, professor of management science and brain and cognitive sciences at MIT, studied why people were sharing disinformation on social media, he found something surprising. Subjects asked to gauge the accuracy of certain headlines were quite good at doing so—even if the headlines didn’t align with their preferred politics. Others, asked whether they would share a post but not asked to think about its accuracy, were much more likely to share posts that were inaccurate but in line with their political outlook. Yet, when the subjects were asked to weigh different factors that led them to share a post, participants overwhelming said that accuracy was very important. Despite “all these narratives going on in the popular culture, and among a lot of academics, that [sharing] is all about politics and identity and politics trumps truth,” Rand says, “our data were just totally not consistent with that.”

He believes that most people share disinformation on social media not out of malice, but out of inattention. The most widely shared theories are not necessarily believed by everyone who shares them, but spread regardless. When participants were asked to rate the accuracy of every news post before stating how likely they’d be to share it, they shared fake news less than half as often. Even subjects who were asked at the beginning of the study to rate the accuracy of a single headline shared less fake news. Though Rand thinks the spread of disinformation is both a top-down and a bottom-up process, he thinks it’s easier to address problems on social-media platforms themselves than deal with the TV networks that share disinformation. The platforms, he thinks, could prompt people to rate the accuracy of random posts, priming users to think about the truth before they decide to share.

False information has been plentiful, spread for financial or political gain, out of malice, or by mistake.

Photograph by Jeremy Hogan/SOPA Images/LightRocket via Getty Images

Other researchers focus on incentivizing good behavior when combating the spread of disinformation. Chris Bail, Ph.D. ’11, professor of sociology, public policy, and data science at Duke University, argues that people are sharing information primarily from a desire to create an identity. Because platforms like Twitter and Facebook are most likely to display posts or groups that attract the most engagement, the easiest way for people to achieve a sense of micro-celebrity on such sites is to post controversial, highly partisan content. In his book Breaking the Social Media Prism: How to Make Our Platforms Less Polarizing, Bail argues for a kind of platform that rewards not the most outrageous, attention-seeking posts, but those that make the most cogent arguments. He thinks sites like Twitter and Facebook could reward not just raw engagement metrics, but also posts that resonate with a broader swath of political viewpoints.

To attain a public-interest internet, Joan Donovan’s ultimate goal, she thinks people need access not just to politically palatable information, but also to news that is “timely, local, relevant, and accurate,” curated by librarians. She thinks some of the most popular sites, like Facebook, have become basic public utilities and therefore should be required to provide important news and updates to their users, rather than simply assembling feeds meant to provoke. An economic model based on advertising—sites now make more money as they gather more personal information—needs to be strictly monitored, she suggests. And as Facebook moves into hardware and banking, selling smart displays and creating its own cryptocurrency, she believes the need for the government regulation becomes even more urgent. “The reason that we have governments, and so many of them, is so things like this cannot happen,” Donovan continues. “We will not enter into a situation in which very, very rich people who own all the conduits of information…are then calling the shots.”

And when disinformation starts to take shape online, Donovan doesn’t believe that it’s always the mainstream media’s job to cover it. That, she thinks, often does more harm than good, spurring more publications to publicize the same disinformation and encouraging more people to seek radical content online. She thinks “strategic silence,” her term for bypassing stories that could spread disinformation, can stop many media-manipulation campaigns in their tracks.

Every so often, Donovan believes, society is given a glimpse into the future. For her, January 6, 2021, was that moment. “I don’t know how January sixth didn’t end in more bloodshed. A shot was fired in the Capitol; someone died in the Capitol,” she says. “When that happens, and you’ve got a mob that large, we are very, very lucky they weren’t networked in a way that would have allowed a single entity to say, ‘Guns up.’ We are very, very lucky we weren’t at that stage of centralization of communication. Now’s the time to do something different.”