As a serial entrepreneur, who had founded some 30 businesses, Steven Belkin, M.B.A. ’71, was primed to find out if his Lookout Farm in Natick, Massachusetts, could succeed not in spite of the pandemic, but because of it. “‘Open an outdoor restaurant?’” he says, sitting at a picnic table with panoramic views of the farm’s 180 acres of rolling hills and orchards. “Everybody’s telling us, ‘All the restaurants are closing, what do you mean you’re opening one?’”

The idea arose when the farm’s taproom, featuring hard cider and craft beer brewed on site, closed in March 2020 under COVID-19 restrictions. Given the existing kegs and abundance of picturesque open space, Belkin and his son-in-law Jay Mofenson (head of the beverage companies and a farm manager) envisioned a new use for the property: draw hungry crowds eager to be outside and active, but safely distanced from others.

Jay Mofenson, Steven Belkin, and Amy Belkin enjoying time outside.

Photograph by Stu Rosner

Belkin and Mofenson quickly absorbed the how-tos of restaurant operations, developed a plan, and won local government approvals. Two months later, they’d constructed a tented outdoor kitchen with grills and hired Jason Gorman, a James Beard semi-finalist for the Best Chef Midwest region, to conjure what Belkin calls a menu of “elegant, high-quality, picnic-type food.” Then they trained waitstaff, set up 140 picnic tables outside, 18 feet apart, and opened The Lookout restaurant.

“It was a huge success,” Belkin says, relishing the origins story while seated at a table with his wife, Joan, and Mofenson, awaiting his Ultimate Wagyu Cheeseburger and a lime rickey. “We think—with the feedback we got from customers and vendors—that we became the largest restaurant in New England to be developed from scratch during the pandemic.” Within weeks of opening, they were feeding more than 1,000 people a day. During the winter, diners were moved to tables under heat lamps inside the farm’s 16,000-square-foot greenhouse. “It was the only place around that people could go and eat in a safe environment,” he adds. “So, while we were used to being 100 percent farming—which is a very risky business, struggling to break even—this year we’re going to do 80 percent restaurant and 20 percent farming, and we’re hopefully now going to make a profit.”

In May, with another acre of dining space added on the far side of the outdoor kitchen, the tables were again outdoors—serving families, businesspeople, and young professionals out with friends, along with baby- and bridal-shower celebrants and guests gathered for charity fundraisers. Mofenson has also partnered with the Center for Arts in Natick for an August concert. This fall, the restaurant will be in full swing, as will the traditional pick-your-own ventures through orchards of, in the fall, apples and Asian pears.

Diners spread out across the fields enjoy drinks and food from the kitchen

Photograph courtesy of Lookout Farm

When he bought Lookout Farm in 2005, Belkin planned to eventually make it pay for itself. Established in 1651, it is among the oldest continuously worked farms in the United States, and had already been operating as a wholesale and U-Pick orchard under its previous owner, who had invested in the place for a decade, improving the soil, planting thousands of fruit trees, and laying down the red-brick pathways. Even so, the farm ran a deficit and, despite its natural beauty and legacy, struggled to engage people for longer than it took to stroll around and fill a basket of apples.

Belkin, who grew up in a lower-middle class family in Grand Rapids, Michigan, studied business and engineering at Cornell, and arrived at Harvard Business School during the turbulent late 1960s. A business education within that cultural context greatly influenced the rest of his life. “I wasn’t limited by saying ‘This is just the way it is and you’ve got to follow the establishment, you’re got to follow the rules,’” he said during a 2001 interview for the HBS Entrepreneurs Oral History Collection, at Baker Library. “I always took an ethical approach to things, but I always pushed. What are the rules, and can we change these rules or can we expand these boundaries?”

Soon after graduation he became a progenitor of direct-mail and affinity marketing, turning what was initially Trans National Travel, the subject of a Harvard Business School case study, into the current, diversified holding company Trans National Group. (He was a co-owner of the Atlanta Thrashers and Atlanta Hawks as well.) Yet he’s also committed to living “a balanced life,” for both himself and his employees. “The greatest risk of an entrepreneurial career is how you handle stress…and obstacles,” he said in the oral history: “If you can’t maintain a positive attitude and stay relaxed, it’s going to take a very expensive toll on you both physically and emotionally.” The farm, he still finds, fosters a sense of calm and fresh perspective on what’s truly valuable in life.

The Belkins can see the place from their longtime Weston home six miles away, and were among the parents who took their children there to pick apples. They also had friends whose home abutted the land. “Whenever we went out there, we’d think this site was just so beautiful,” he recalls. “It feels like you’re out in Napa Valley because of all the espaliered trees, and how they’re lined up. And the trellises with the grapevines.” After the owner died in 2004, the Belkins were among a host of developers who offered to purchase the property, he says, but “we were the only ones who wanted to keep it as a farm, and as a community asset.” The day they closed on the deal, their daughter Julie was married on a hilltop, now near the charming playground Belkin built to make the farm more of a destination.

Grapevine-trellised walking paths

Photograph by Stu Rosner

From the start, he and his farm-management team strove to increase fruit production, wholesale revenue, and U-Pick operations, and succeeded to the point of nearly breaking even. But competing with agribusiness production models remained a serious struggle until Mofenson (married to the Belkins’s daughter Amy, M.B.A. ’07) began serving hard cider, pressed on site, in the taproom in 2017.

Recognizing Belkin’s need to boost income and his own dissatisfaction lawyering for the insurance industry, Mofenson found he was much happier working outside, and on farm-related projects. “It’s just a serene place and I find it very grounding,” he says. “The views are spectacular, beautiful rolling hills and agricultural lands, and if you can sit here and enjoy a hard cider or beer, have some good food with friends, where else would you want to be?” Figuring out how to build a hard-cider operation using heirloom apples and the farm’s strawberries, peaches, and pears, and how to engage visitors in sustainable agriculture, felt like a worthwhile challenge. “It was exciting to have the opportunity to create,” he says. “Up until that point I had not been able to use creativity as a skill set.”

Some 15 varieties of hard ciders are currently served on draft at The Lookout restaurant, and canned in four-packs for sale at the farm’s curbside market. Row 7, for example, is made from “tart, bitter-tasting apples, specifically for their tannin content and fermentable sugar,” he says. But other ciders, like the smaller-scale production of 1,200 gallons of Strawberry Fields—involving labor-intensive fruit harvesting—are also available. This fall look for the Pearadox, along with Pumpkin Patch, a brew with nutmeg, cinnamon, coriander, and allspice, Mofenson says, made from sugar pumpkins that help form the base—part of continuing efforts “to integrate as much as we can grow into the finished product we can sell.”

Two years ago, Mofenson added a beer-brewing company to the mix. Experiments with growing hops, and brewing methods, produced batches of craft beer, but because the farm can’t grow and process the volume of hops required, the company also purchases hops grown elsewhere. The Lookout typically offers six to eight varieties of cider and beers on tap and most of the proceeds are funneled right back into farm operations. People often hold romantic views of working the land, he points out, but “farming is a very complicated adventure and requires a lot of ingenuity in expanding your business model…the mission is to create the best agricultural experience we can for people—and that, then, will support the farm.”

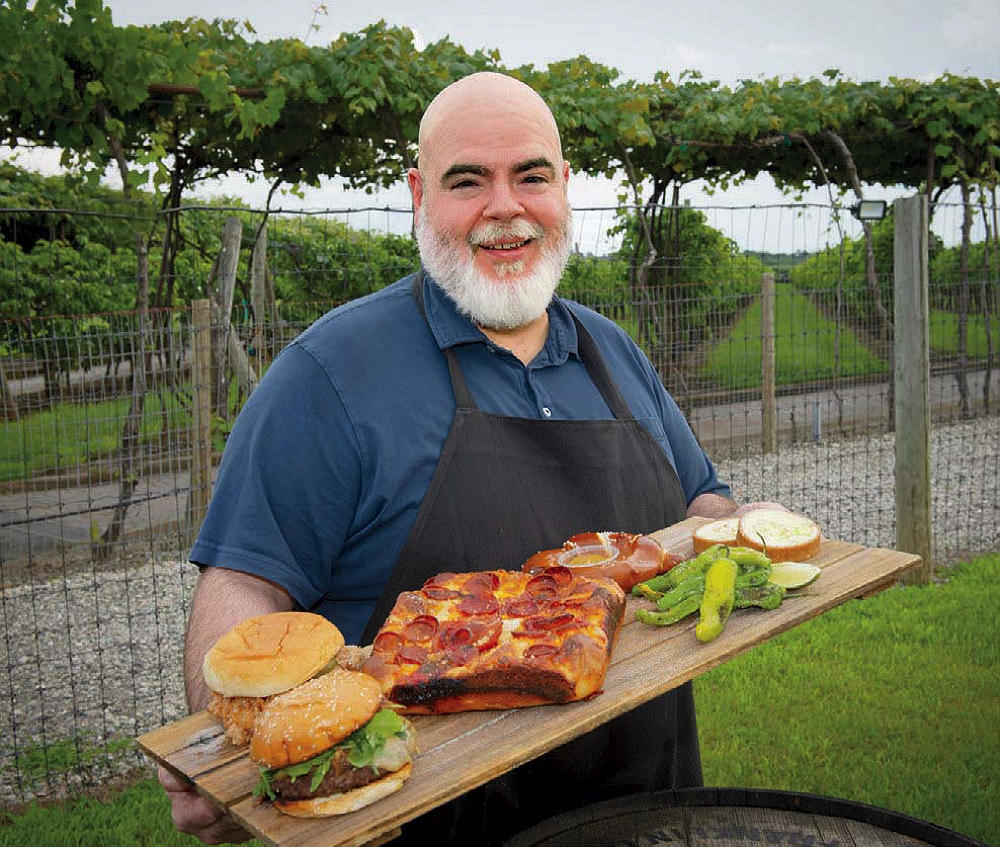

The restaurant has quickly become the site’s touchstone venture—and Belkin’s burger arrives with his chief ingredient for success in the kitchen: Chef Jason Gorman. “So what Steve has here,” Gorman says proudly, is the Lookout’s signature burger. “It’s topped with smoked Gruyére cheese, on a Hawaiian bun, and then we make a porcini mushroom-bacon jam on there, and a little bit of arugula that kind of balances the sweetness.”

“It’s a fabulous dish,” Belkin says, turning his paper plate to better examine the food.

“We wanted to create something that was really unique to us, give people a reason to come,” Gorman notes. “Because,” he gestures across the landscape, “obviously, I’m competing with a lot here. I think we have the best dining room in Massachusetts.”

Robust lobster roll

Photograph courtesy of Lookout Farm

The restaurant also serves fresh salads, lobster rolls, and deep-dish pizza. Gorman’s pastry-chef wife, Jennifer, is in charge of desserts. The key-lime tart and whoopie pie are excellent, but try the more adventurous “strawberry pretzel Jell-O shot”: a base of salty crushed pretzels topped by vanilla whipped cream cheese and a layer of strawberry Jell-O laced with fresh fruit. Mofenson had tried it the night before, and vouched for it, as Belkin continued marveling at his burger. He also orders the margarita deep-dish pizza, a new dish Gorman developed for the 2021 season.

The restaurant is open six days a week: for dinner on Tuesday, Wednesday, and Thursday, 4-8; lunch and dinner on Friday, noon-8; and brunch, lunch, and dinner on Saturday and Sunday, 10-8. Time your visit to watch the sunset. “It sets right over there,” Belkin says, pointing across the wild meadows to the west. “It’s just gorgeous because we have this huge sky. And once people start eating outdoors, they really like it; they don’t want to go back indoors.”