Known for bold, full-length paintings of urban black Americans, artist Barkley L. Hendricks was also a prolific street photographer. From his adolescent days in North Philadelphia through college and graduate school at Yale and a teaching career at Connecticut College, the debonair artist rarely traveled without his camera. Thousands of images, catalogued since his death in 2017, inspired content for his oil paintings—and whatever else caught his playful and discerning eye. Youths with boom boxes, playing basketball, or striking poses in bling. Women’s legs and shoes (which held a special, seemingly erotic fascination). He was clearly drawn to anyone with personal flair and strength, or an air of “cool.” Many of his photographs are more than documentary snippets, they are elegant or elegiac compositions that brim with their own vitality as stand-alone works—as revealed in the Rose Art Museum’s exhibit “My Mechanical Sketchbook”—Barkley L. Hendricks & Photography, on view through July 24.

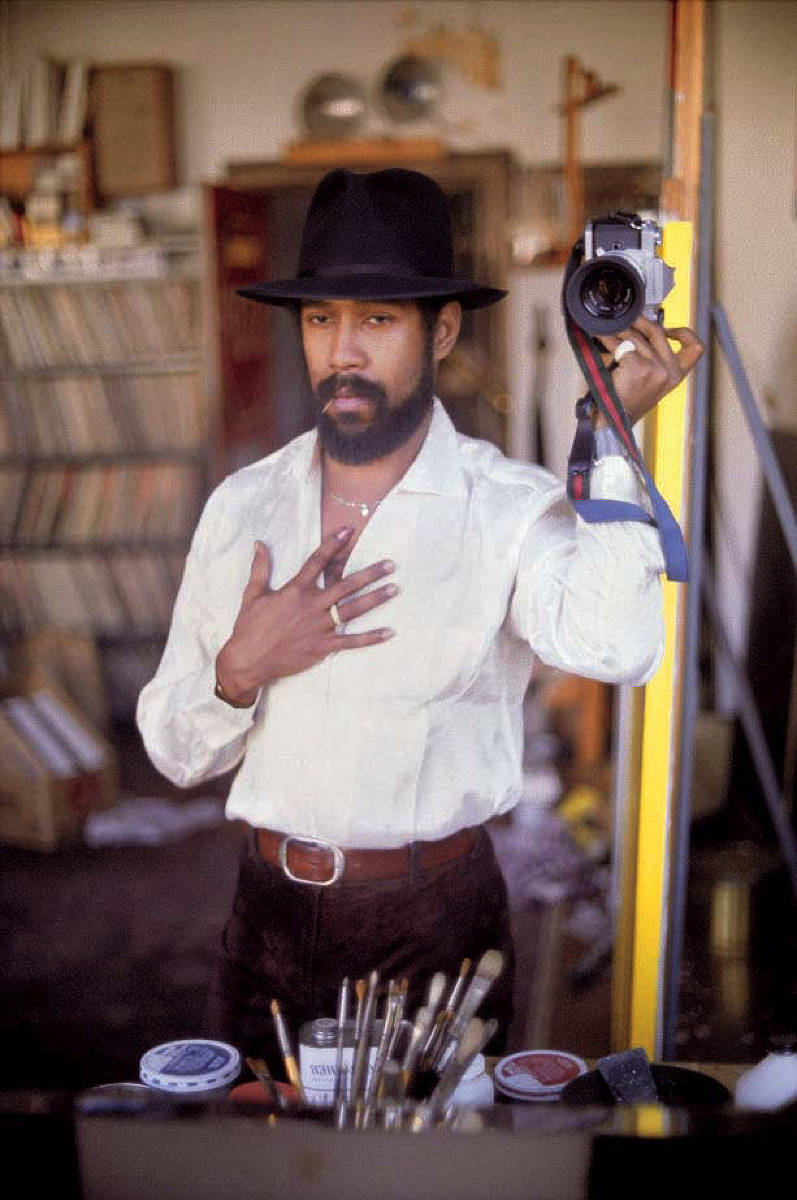

Self Portrait with Black Hat, 1980–2013 (taken in his New London, Connecticut, studio)

Photograph ©Estate of Barkley L. Hendricks/Courtesy of the artist’s estate and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York

“Hendricks had an astute talent for capturing the ways people chose to fashion and present themselves to a world that often denied their humanity,” notes guest curator of African and African diaspora art Elyan J. Hill. “The photographs convey the confidence, defiance, pride, beauty, and joy of people taking pleasure in being seen and desired.” More than half of the images have not been publicly displayed, which helps highlight the painter’s “multiple modes of creativity side-by-side,” she adds, “and in dialogue.”

Untitled, 1982

Photograph ©Estate of Barkley L. Hendricks/Courtesy of the artist’s estate and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York

A natty dresser with a performative inclination, Hendricks also often turned the lens back on himself, sharing in his wider, painterly exploration of black masculine guises. This objective focus challenges “stereotypes that project fear and hypersexuality onto Black bodies,” the exhibit text points out. Yet as the artist in charge, often with a camera present in the photograph itself (as in Self-Portrait with Black Hat, below), Hendricks is also mirroring, or doubling-back on, these perceptual presentations by imposing his way of seeing, notes Hill: “He is in the foreground, but so is the camera.” It’s something of a postmodern trick. But within the new focus on his photographs—in the age of selfies, the dominance of visual culture, and Black Lives Matter—Hendricks’s reflections of selfhood and status, and on the interplay between subject and object, viewer and viewed, feel especially relevant—and revelatory.