Sometimes it truly feels like flying. That’s how acrobat Anna Soltys Morse, A.L.B. ’18, describes a good day at work. “When things are really well-timed between two people, there’s this moment where you’re like, ‘Oh, that was perfect,’” she says. “You feel the right impulse from your partner, you can see that they’re in the right place and you’re in the right place, and you get a clean catch, nothing moves. At that moment, you really feel the connection between the hands, or the feet. That’s probably my favorite thing.”

Anna Soltys Morse (top left, red shirt, upside down) with castmates in "Branche"Photograph by Émékue Rivard-Boudreau

Soltys Morse practices what’s called hand-to-hand acrobatics, a circus art that uses no equipment, just the combined strength and agility of (usually) two people—a flyer (Soltys Morse) and a base (sometimes called a porter)—balancing on top of each other to execute tumbling throws, leaps, lifts, and gravity-defying poses. “It really is about the connection,” she says, “about the way you can make something together with other people. I think that’s more appealing to me—it’s not an individual discipline. It’s an art form that depends on other people.”

Plus, that feeling of flying: “Incredible.”

In videos of Soltys Morse training and performing with her longtime acrobatic partner, Pasha Muravyev, it’s easy to see what she means. In one, she cartwheels into his arms, and then—somehow (even in slow motion, the move is hard to comprehend)—she flips backward over him, before landing in a handstand above his shoulders. In another, she holds his hands and swings her folded body between his legs like a pendulum; an instant later, the momentum carries her back up over his head, rising, rising, until the two become one long mirror image of each other, legs and arms fully extended, Muravyev standing on the floor looking up at Soltys Morse, who, looking down, is doing a handstand, balanced on his upturned palms.

It has been a long journey to this kind of work. Soltys Morse grew up in Cambridge, a child in perpetual motion and obsessed with gymnastics (which set her apart in her academic-oriented household). “I always loved to climb and jump and roll around,” she says. “I love the feeling of the world turning when you do a cartwheel, that sensation in your brain.” She began practicing gymnastics at age 10—late for a competitive career, but as early as her reluctant parents would allow. She kept training until she passed the gym’s age limit in high school. By then, she had started working part-time as a wilderness guide—a summer job that became a full-time occupation after her first college experience, at a small school in Vermont, “didn’t click.” For several years, Soltys Morse led outdoor trips, mostly in the United States and Canada. She loved the outdoors and the physicality of the work, less so the teaching. When she decided to return to school for her bachelor’s degree, she chose Harvard’s Extension School for its flexibility. “It allowed me to take a seasonal job, where I might not have electricity or an internet connection, and then take a break and go to school.” At 28, after five years of study, she graduated with a concentration in humanities.

By then, acrobatics had become the center of her life. Moving back to Cambridge, she’d stumbled into Esh Circus Arts, a small school and training center. “The first time I went there, just to take a trapeze class, I remember walking in and thinking, ‘This is it.’” She trained at Esh for a couple of years, and then, searching for a trampoline coach to help broaden her skills, ended up at Cambridge Community Gymnastics, a now-shuttered program on MIT’s campus. It was there she met Muravyev, then an MIT computer-science student, and the two began learning hand-to-hand acrobatics together. “It took more work, emotionally and physically, than I would have imagined,” she says, in part, because the United States lacks the institutional infrastructure for circus arts that exists in Canada, Europe, Russia, and China. “I knew so little at the beginning,” she says. “There was a lot of, you know, Googling a question and coming up with only French sites.” When she and Muravyev began training together, they didn’t have a consistent coach. “We did a lot of guessing and watching videos of people doing tricks in slow motion to try to see how it worked.”

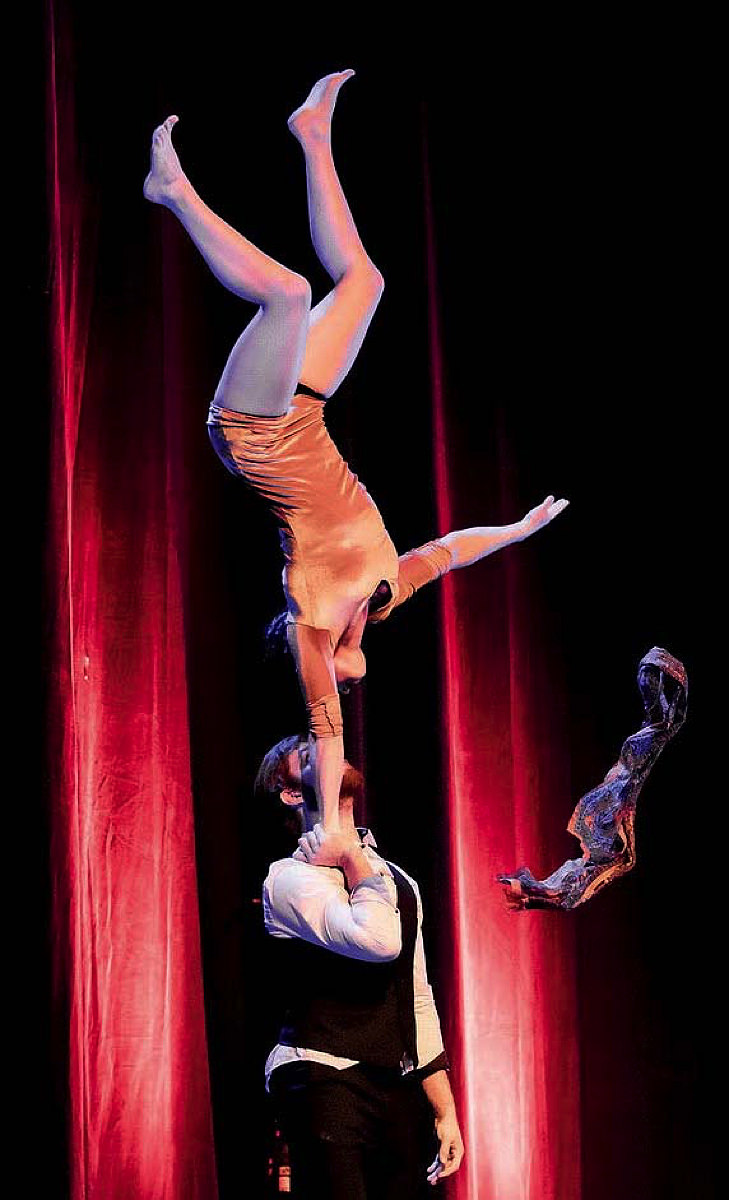

Anna Soltys Morse performing with with her longtime partner Pasha Muravyev Photograph by Norbit Whitney

In 2016, they enrolled as a duo at École de cirque de Québec, a professional circus school in a former church in Québec City, Canada. The three years they spent there were grueling, exhilarating, transformative. Soltys Morse and Muravyev emerged with a deeper bond and stronger skills: agility, balance, “air awareness.” In an odd way, she says, hand-to-hand performance is like a biathlon. “They have to ski fast, because it’s a race, but then they have to shoot accurately, and for that you need to be still,” she says. “So, you’re doing something dynamic, and then immediately afterward, something static—switching from power to a meditative state very quickly.” One video clip shows Muravyev throwing Soltys Morse into an overhead somersault, after which she comes to a sudden, graceful halt at his waist, her face turned outward toward the audience, her back arched, arms extended, legs stretched behind him as he supports her torso, the curve of her body looking like the prow of a ship, or a bird in flight.

They graduated a few months before the pandemic, and their first show—in a large cast performing amid multicolored fountains and pools in an ocean-themed production in Hong Kong—closed almost as soon as it had opened. As COVID-19 shut theaters around the world, they kept training, and waited. Last year, Soltys Morse moved to Montréal, to join the cast of a new production that Muravyev will join this summer. Called Branché, it is a traveling show, performed in woods and parks, and focused on the issue of climate change. A cast of eight acrobats uses the natural environment—rocks, trees, rivers—and each other as their only equipment, conveying a story of environmental collapse (one climactic scene crowds the whole group onto a single rock, where they jostle and compete for space) and potential restoration. A collaboration between Montréal’s Barcode Circus Company and the artists’ network Acting for Climate, Branché has three touring casts, in Canada, the United States (where Soltys Morse is a member), and a new one planned for Europe.

Anna Soltys Morse (red shirt) performing in Branche, an outdoor acrobatics show focused on climate changePhotograph by Cherylynn Tsushima

The show is a little different every time, Soltys Morse says, depending on each venue’s terrain (“There are a lot of sharp, irregular shapes out there”), but the troupe often tries to time its final scene to the golden light of sunset. “It’s really beautiful,” she says, and in a certain way harks back to an earlier circus era, with tents and animals and pure spectacle. “Circus is really an intuitive entertainment; it’s always been that way,” she says. “It’s just fun to watch somebody do something that seems impossible.” Paradoxically, that makes it an effective vehicle for a message like climate change, she believes. “In a way, circus is a niche art, but in another way, it’s not—it’s accessible, it’s not esoteric.” Those beautiful, impossible tricks “draw you in and open you up to ideas.” Another kind of flight.