“There are people who come to Mystic just so they can get stuck in traffic at the drawbridge,” says historian Nancy Steenburg ’72, a resident of the picturesque Connecticut town since 1980. The captivating bascule bridge that connects to the village center raises a moveable “leaf” hourly to let sailboats and yachts on the Mystic River pass beneath it. Using an ancient technology not unlike an equal-arm balance, the bridge deploys a heavy counterweight to raise the 218-foot central span for five minutes about 2,200 times per year. Like many features of this charming seacoast destination, it’s something the rest of us rarely encounter.

Boats passing the iconic Mystic drawbridge

Photograph by Stan Tess/Alamy Stock Photo

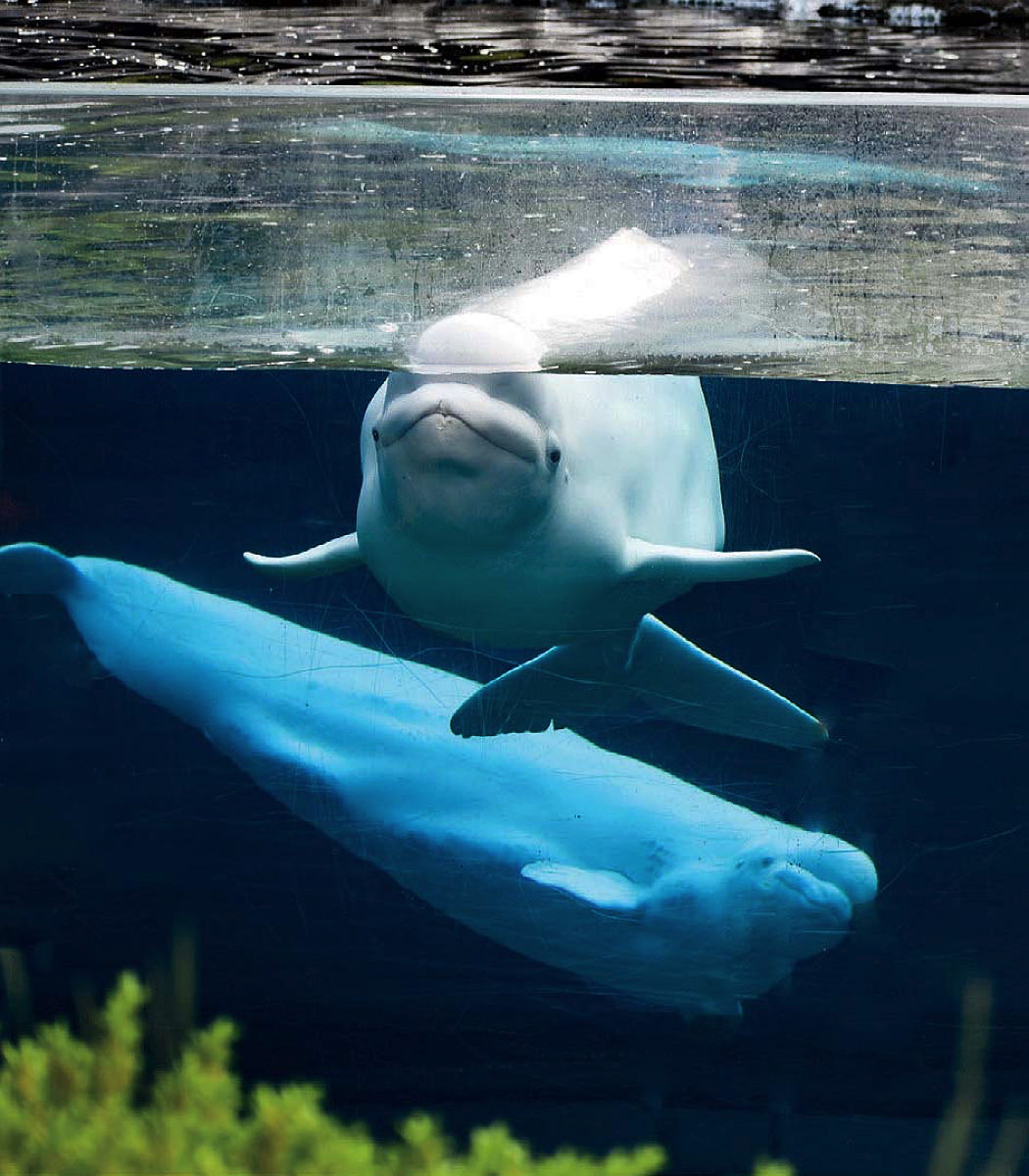

Take beluga whales. From an underwater viewpoint, you can watch these graceful white Arctic natives swimming in a chilled pool at Mystic Aquarium, home to the only belugas in New England. Or at the Mystic Seaport Museum, walk the decks of the 1841 whaleship Charles W. Morgan, the oldest American merchant ship still afloat. Perhaps you’ve never eaten pan roasted monkfish at a restaurant that was once a marine-engine factory. During Prohibition, the Engine Room restaurant’s brick building housed the plant that produced Mallory motors. These powered small speedboats fast and agile enough to ferry cases of bootleg liquor ashore from anchored smuggler vessels, outrunning Coast Guard interceptors en route.

Maritime culture saturates Mystic life. The coastal setting, where the Mystic River flows into Fishers Island Sound and by extension Long Island Sound and the Atlantic Ocean, encourages sailing and all forms of boating. You can get out on the Argia, a traditional gaff topsail schooner that offers day sails and sunset cruises from May 1 through mid-October. Or take the 1908 coal-fired steamboat Sabino, a National Historic Landmark that provides day tours and evening cruises. On the weekend of June 24-26, with WoodenBoat magazine, the Seaport Museum hosts the 30th Annual Wooden Boat Show, with speakers, demonstrations, a Concours d’Élegance, and an “I Built It Myself” category.

The Seaport Museum’s sprawling campus and 130 buildings make it one of the largest institutions—and visitor magnets—in the area. It aims to keep alive and, when possible, create a direct experience of the seafaring culture that has animated Mystic, and much of the world, for centuries. (The Museum owns and operates the Sabino, for example.)

Charles W. Morgan whaleship

Photograph by James Nesterwitz/Alamy Stock Photo

By 1784 Mystic had emerged as a boatbuilding center, one that produced more than 600 vessels during the next 135 years. It prospered in the whaling era, and the aforementioned Charles W. Morgan is, in fact, the very last wooden craft of an American whaling fleet that once numbered more than 2,700 vessels. The Museum brings that Moby Dick era to life, along with much of the East Coast’s seagoing past.

From left: A glimpse of Mystic Seaport's many historic buildings; the Engine Room’s outdoor dining

From left: Photograph by James Nesterwitz/Alamy Stock Photo; courtesy of the Engine Room

For example, a vivid recreation of a nineteenth-century seaport village lets visitors wander among a cooperage and a shipsmith shop, a chandlery, sail and rigging lofts, and a nautical instruments shop, as well as an oyster house, salmon shack, and many more. Schaeffer's Spouter’s Tavern is a working pub open to ticket-holding museum visitors, who can quaff a brew either in the cozy barroom or at al fresco tables on the grass. If the village feels real, that’s because it pretty much is: these aren’t reproductions, but actual nineteenth-century trade shops and businesses transported to the Seaport Museum from places around New England. In most cases they are actively doing business today in their historic niches.

Dine al fresco at Spouter’s and explore a replica of the Brant Point Lighthouse (the original marks Nantucket Harbor).

Photographs courtesy of Mystic Seaport Museum

Founded in 1929, the Museum owns vast research collections that include more than 300 classic boats of all kinds, two million still images, and 2.5 million feet of film (now being digitized for worldwide scholarly access).

This summer, a new exhibit, “Story Boats: The Tales They Tell,” opened. It includes the 1914 knockabout sloop Vireo, which Franklin D. Roosevelt, A.B. 1904, LL.D. ’29, sailed after contracting polio in 1921 on what is believed the last day he was able to walk without assistance. The exhibit will also include the Tango, a bright-orange foot-pedal powered craft that Dwight Collins pedaled from Newfoundland to England in 41 days in 1992, the fastest recorded human-powered Atlantic crossing.

Beluga whales

Photograph courtesy of Mystic Aquarium

So much for stuff that floats. Diving deeper (more than 2,500 feet, in fact, when in the ocean), those Arctic beluga (Russian for “white”) whales charm with their suppleness and smiling appearance in the Mystic Aquarium’s Arctic Coast exhibit (whose 750,000-gallon pool is the largest outdoor beluga habitat in the United States). Sometimes they even interact with visitors, and in summer, their keepers apply sunscreen to their melon-shaped heads, as their skin is adapted for icy conditions. Small by whale standards at 10 to 18 feet, belugas have “near threatened” status largely due to human activities such as fisheries, oil and gas development, offshore drilling, pollution, climate change, and even ocean noises, to which, as one of the most vocal singing whale species, they are sensitive. For more than a decade, the Aquarium has worked closely with native people of Point Lay, Alaska, on conservation-focused beluga research.

From left: A northern fur seal (named Tuk), lagoon jellyfish

Photographs courtesy of Mystic Aquarium

Next pool over are harbor seals, which can sleep submerged for 30 minutes and swim at up to 25 M.P.H. They share the pool with Northern fur seals, including Ziggy Star, a female with a neurological condition who was rescued off California and reached the Aquarium in 2014. Ziggy underwent a first-of-its-kind pinniped brain surgery in 2017 and soon enough recovered her usual routines. Nearby, visitors can encounter the only Steller sea lions in this country outside of Alaska. Named after German naturalist Georg Wilhelm Steller, who first described them in 1741, they are amphibious and will climb onto rocks to catch some sun and emit loud burp-like cries.

Penguins

Photograph courtesy of Mystic Aquarium

The African penguins (native to the coasts of South Africa and Namibia) that arrived at the Aquarium in 1989 have their own kind of charm. Five of the birds remain alive 33 years later, enjoying triple the lifespan expected in the wild, thanks to the lack of predators. One penguin pair mated (typically) for life, and now, 30 years later, have both children and grandchildren around. Today, the flock includes 31 adults and three baby penguins born this year. Sadly, 97 percent of African penguins have disappeared over the last century.

Indoors at the Aquarium, marvel at beautiful displays like tankfuls of translucent “jellies,” described as, “no brain, no heart, no eyes, 90 percent water—and very alive!” Graceful, pulsating swimmers, some jellies take on the color of whatever they just ate. Octopuses, in contrast, do have brains—one in each tentacle, making them world-class multitaskers: one tentacle can be opening a clam while another searches for food and a third seeks a place to hide—all at once.

At the Touch Habitat, an indoor pool where several species of non-threatening sharks and rays swim, visitors may stand close enough to gently touch their backs as they glide past. As always, the Aquarium adds education to the experience, informing guests that myths about sharks have put them among the most misunderstood creatures in the animal kingdom, that in fact they are essential to the health of the ocean ecosystem as apex predators. Sharks’ fellow elasmobranch, the stingray, shows its unique form in variants ranging from a few inches to six and a half feet across—and weighing up to 790 pounds. Unfortunately, extinction now threatens 25 percent of all shark and ray species.

After touring the Mystic Aquarium and Seaport Museum (the Mystic Pass offers discounted admission to both) you may have an appetite. Reflecting its popularity with tourists, the village of 4,200 residents is home to dozens of restaurants. Cuisines range from Mexican to French to Indian to Thai—but seafood is ubiquitous. The aforementioned Engine Room, for example, serves lobster bisque, steamed mussels, fluke, monkfish, and local fried “fish and chips,” as well as the usual burgers and sandwiches.

Other options include the seafood paella at the S&P Oyster Restaurant and Bar or the raw bar at the riparian Oyster Club. At Mystic Pizza, the setting of the eponymous 1988 film that launched Julia Roberts’s movie career, they still serve creditable slices, though Mango’s Wood-Fired Pizza Co. may have an even larger local following.

For dessert, or just a fun, bright place for coffee and a scone, head to the Sift Bake Shop. Founded by head pastry chef Adam Young and his wife Ebbie (he won the Food Network’s “Best Baker in America” bake-off in 2018 with his version of a Sachertorte), Sift offers classics with a twist: a cheese and guava Danish, an oatmeal blueberry cookie, or a chocolate raspberry croissant. But most luxurious is a generous slice of “Opera Cake,” of a type served at French opera intermissions, with its layers of almond sponge cake soaked in coffee syrup with chocolate and coffee ganache, covered in a chocolate mirror glaze.

Just down the street from Sift, peek inside Danforth Pewter, a specialized shop built on 50 years’ experience selling handcrafted pewter items. There’s a Colonial-style beer mug, the “President’s Mug,” and oil lamps whimsically labeled as “scallion, shallot, and onion” in a nod to their shape. Or, not far away, check out Mystic Knotwork, which bills itself as the only one of its kind in the United States. Owners Matt and Jill Beaudoin employ 20 dexterous pairs of hands to render bracelets, doormats, coasters, bottle stoppers, pet toys, wreaths, centerpieces, and more from nautical knots. They also supply hand-tied accoutrements for those tying the knot themselves. “Within 10 or 15 miles of the ocean,” notes Matt Beaudoin, “at least 15 percent of weddings have a nautical theme.”

The Lighthouse Museum, in Stonington

Photograph by Stephen Saks Photography/Alamy Stock Photo

Travel across the bridge about five miles east to the Lighthouse Museum in Stonington. (Mystic is not legally a town, but a village and “census designated place,” whose borders overlap those of the towns of Groton and Stonington.) Built in 1840, it remained an active lighthouse until 1889, and opened as a museum in 1927. A permanent exhibit, “My Freedom is a Privilege that Nothing Else Can Equal,” limns the life of Venture Smith (1729-1805). Captured in Guinea and enslaved, Smith eventually purchased his family’s freedom and spent his last decades as a prosperous businessman in southern Connecticut.

Mystic resident Nancy Steenburg, an adjunct professor of history at the Avery Point campus of the University of Connecticut and project historian for the exhibit, spent more than 17 years researching Smith’s life, which he documented in an autobiography dictated to a local schoolteacher and published in 1798. It’s considered the earliest slave narrative in the United States. Smith made the most of his freedom and eventually owned 110 acres of land, 10 houses, and 20 boats. In a way, the seafaring life bookended his American journey; after disembarking as a slave from Africa, inner resourcefulness, savvy, and an unconquerable spirit eventually made him captain of his own fleet.

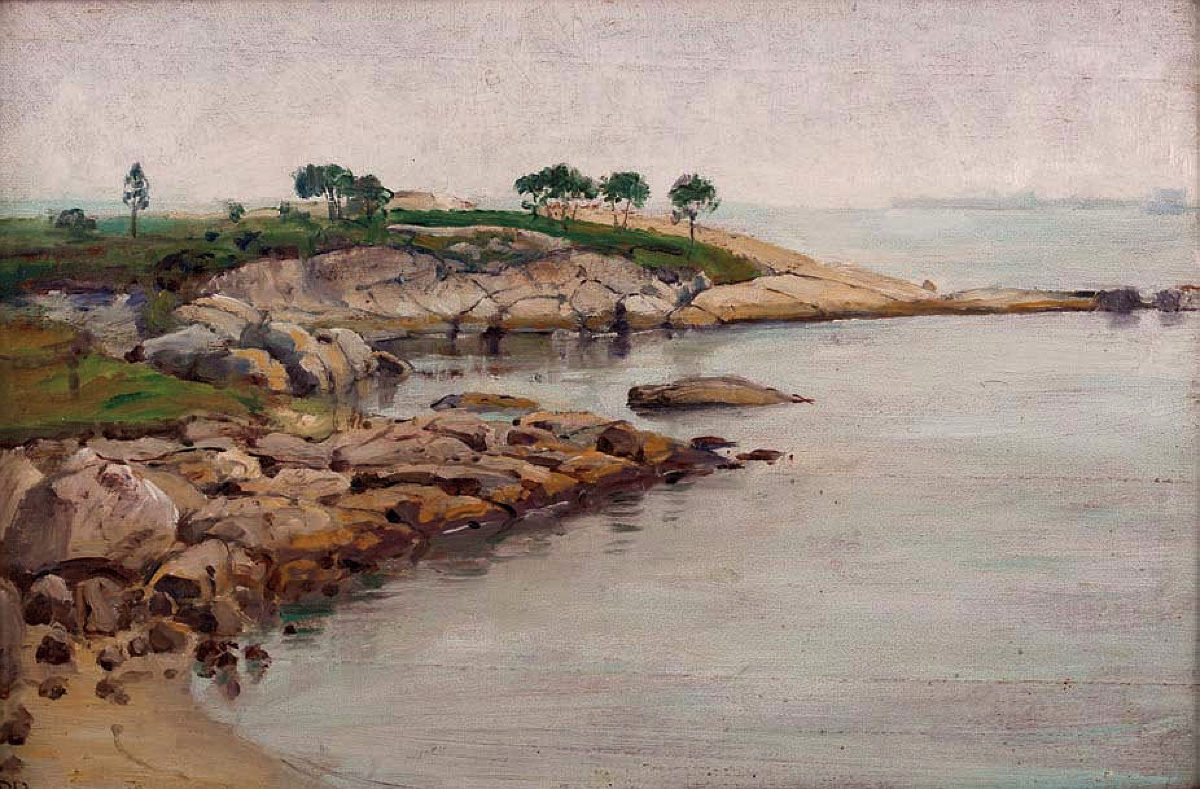

View of Groton Shoreline (1935), by Anna Richards Brewster, part of the "Picturing Mystic: Views of the Connecticut Shoreline, 1890-1950" exhibit, Lyman Allyn Art Museum, in New London

Image courtesy of the Lyman Allyn Art Museum

Turning to a different kind of history, this summer the Lyman Allyn Art Museum, in New London, mounts an exhibit, “Picturing Mystic: Views of the Connecticut Shoreline, 1890-1950.” It displays 60 landscapes featuring natural scenery and seaside vistas from Mystic’s heyday as an art colony in the early twentieth century.

Whether via paint on canvas, historic objects and narratives, or living ocean creatures, Mystic delights in the variety of ways its rich coastal culture expresses itself. It’s all only a bascule-bridge ride away.