With a deeply researched report released in April and a conference a few days later, Harvard joined the long list of universities that have conducted public investigations into their historic ties to slavery. In Harvard’s case, those ties—direct, financial, and intellectual—extend to the University’s founding, with consequences that continue today. President Lawrence S. Bacow and the Harvard Corporation pledged $100 million to address the injustices.

The 134-page report lays out the findings and reparative recommendations of the Presidential Committee on Harvard and the Legacy of Slavery, formed in 2019 by Bacow. The account it gives is severe. “Many of you will find it disturbing and even shocking,” he wrote in an accompanying message to the community. Tomiko Brown-Nagin, dean of the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study, who chaired the committee, spoke in an interview of the “painful truths” uncovered in the report.

The University’s entanglements with slavery were in some cases direct: the committee found records of more than 70 people who were enslaved by Harvard presidents, overseers, and faculty and staff members—many more than previously known. A man known only as “The Moor,” who was enslaved by the first Harvard schoolmaster, Nathaniel Eaton, served the College’s earliest students. “Enslaved men and women served Harvard presidents and professors and fed and cared for Harvard students,” the report states.

Other links were financial or intellectual: the University benefited enormously from the slave trade through investments and donations, and Harvard scholars promoted racist ideas that underpinned slavery and other racial hierarchies. One of the strongest connections the report draws is between Harvard’s early growth and prosperity and the slave trade, first in the Caribbean and later in the American South. The colonial economy’s alliance with the West Indies—trading New England food, fuel, and lumber for Caribbean tobacco, coffee, and sugar produced by enslaved Africans (or for slaves themselves)—included Harvard. “For roughly a century, Harvard had operated as a lender,” the report states, “and derived a substantial portion of its income from investments that included loans to Caribbean sugar planters, rum distillers, and plantation suppliers. After 1830, the University shifted its investments into cotton manufacturing, before diversifying its portfolio to include real estate and railroad stocks—all industries that were, in this era, dependent on the labor of enslaved people and the expropriation of land.”

Moreover, the University received important and defining gifts from donors whose wealth was tied up in slavery and slave trading. Isaac Royall Jr., a sugar-plantation owner in Antigua (who participated in the brutal suppression of a 1736 slave rebellion there), bequeathed the founding gift for Harvard Law School. Samuel Winthrop, the youngest son of the colonial governor, made a fortune in Caribbean real estate and sugar plantations and joined with two other Harvard graduates in 1645 to donate the first alumni gift of property—an apple-tree-covered parcel called Fellows Orchard, which today is the site of Widener Library. Benjamin Bussey, a sugar, coffee, and cotton merchant, left Harvard an estate that is now the Arnold Arboretum in Jamaica Plain. Israel Thorndike, a merchant and slave trader, donated a collection of maps that became the core of the Harvard Map Collection, “the most valuable single collection in existence.” The donors during the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries “were vital to the University’s growth,” the report explains. “They allowed the University to hire faculty, support students, develop its infrastructure, and ultimately begin to establish itself as a national institution.” More than one-third of donations or financial pledges Harvard received from private individuals during the first half of the nineteenth century came from just five men, who made their wealth from slavery and slave-produced commodities.

In describing Harvard’s contributions to race science and eugenics, the report homes in on Louis Agassiz, a professor of zoology and geology and one of the University’s most prominent race scientists. He was a proponent of polygenism, which not only argued for a hierarchy of races, but insisted that they were separately created (see “A Scientist in Full,” May-June 2013, page 22). Agassiz was celebrated in the South; one plantation owner in South Carolina invited him to examine enslaved Africans as “live research specimens.” Afterward, Agassiz commissioned photographer Joseph T. Zealy to make daguerreotypes of seven men and women—Delia, Jack, Renty, Drana, Jem, Alfred, and Fassena—stripped nude, for his “further study” (see harvardmag.com/agassiz-faces-20). These are believed to be the first photographs of enslaved human beings. (The report does not mention that the Zealy daguerreotypes, which remain in Harvard’s possession, are the subject of a lawsuit. In an appeal now pending before the Massachusetts Supreme Court, Tamara Lanier is asking that Harvard give up ownership of the images of her ancestor, Renty Taylor, and relinquish any profits associated with them.)

From the mid-nineteenth century until well into the twentieth, several Harvard presidents and scholars conducted similarly abusive “research,” and their records persist in the University’s collections. The remains of thousands of individual people are also held by the University, most either at the Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology or the Warren Anatomical Museum. Many are thought to belong to indigenous people, and at least 15 are people of African descent who may have been enslaved. In 2021, Bacow established a Steering Committee on Human Remains to conduct archival research and consider options for the return of these remains to their communities or descendants, or their burial, commemoration, and memorialization (see “The Spirit of the Law,” September-October 2021, page 21, on repatriating Native American remains).

Carrying through to the present day, the report charts the long legacies of slavery that persisted well past Emancipation: segregation, marginalization, isolation, exclusion from dormitories, and discrimination in admissions. After the Civil War, despite a “rhetorical commitment” to openness and egalitarianism, Harvard favored white applicants from elite backgrounds and restricted enrollments of “so-called ‘outsiders.’” Largely because of the racist policies of Harvard presidents Charles William Eliot (who served until 1909) and Abbott Lawrence Lowell (1909-1933), the number of black students remained low until the racial transformations of the 1960s. Between 1890 and 1940, approximately 160 black men attended Harvard, an average of about three per year. In 1960, the freshman class of 1,212 students included only nine who were black—a “vast improvement,” the report states. Among the students admitted to the Class of 2026, 15.5 percent identify as black or African American (though not all will enroll), and the report comes at a time when Harvard’s race-conscious admissions policy is under legal threat. In January, the Supreme Court announced it would hear an appeal in Students for Fair Admissions’ litigation against the University, opening an opportunity to curtail affirmative action.

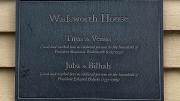

Some of the facts in the report had been discovered already, though never laid out so comprehensively. In 2007, Bell professor of history Sven Beckert began looking into Harvard’s ties to slavery in seminars with undergraduate students, which culminated in a 2011 report, Harvard and Slavery. In 2008, Royall professor of law Janet Halley began probing more deeply the benefactor for whom her professorship is named. Her research spurred student protests that led to the 2016 removal of the Law School’s shield, which had featured the Royall family crest. Also in 2016, then-Harvard president Drew Gilpin Faust acknowledged that “Harvard was directly complicit in America’s system of racial bondage from the College’s earliest days” and established a committee that conducted a preliminary study on Harvard and slavery. That spring, she and John Lewis, LL.D. ’12, the late civil rights leader and U.S. Congressman, unveiled a plaque on Wadsworth House dedicated to four enslaved people—Titus, Venus, Juba, and Bilhah—who had lived and worked there for two Harvard presidents (see harvardmag.com/law-shield-21 and harvardmag.com/harvard-slaves-16, respectively). In 2017, the Radcliffe Institute organized a conference on universities and slavery, where the writer Ta-Nehisi Coates called for institutions to make reparations and Faust, a Civil War historian, acknowledged that recent research on slavery had stripped away the North’s “great alibi.”

To address the injustices it describes, the report laid out seven recommendations. Their implementation will be overseen by a committee chaired by 300th Anniversary University Professor Martha Minow, former dean of the Law School, a member of the committee on the legacy of slavery, and a scholar of international truth and reconciliation processes.

The recommendations, in brief:

• Support descendant communities by using Harvard’s educational expertise to “confront systemic and enduring inequalities that impact descendant communities in the United States,” including the American South as well as the Caribbean. The recommendation calls for “close and genuine” partnership with other institutions such as schools, community colleges, tribal colleges, universities, and nonprofit organizations already engaged in this work.

• Honor enslaved people through memorialization, research, curricula, and knowledge dissemination, “in pursuit of truth and reconciliation,” with a particular focus on giving students the opportunity to “acknowledge and engage with” Harvard’s history of slavery.

• Develop enduring partnerships with black colleges and universities, “in light of the invaluable role of HBCUs in the education landscape and the persistent underfunding of these colleges.” This plan calls for Harvard to fund summer, semester, or yearlong visiting appointments and fellowships for its faculty and librarians at Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs) and for HBCU faculty and librarians at Harvard. For students, the University would establish a Du Bois Scholars program, in which HBCU undergraduates would spend a summer or one or two semesters of their junior year at Harvard—with financial aid from the University—and Harvard juniors would do the same at HBCUs. The program is named for sociologist and civil rights leader W.E.B. Du Bois, A.B. 1890, Ph.D. ’95, the first African American to earn a Harvard doctorate.

• Identify, engage, and support direct descendants of those enslaved on Harvard’s campus, or by Harvard leaders, faculty, and staff. The report called for “educational support” and a yet-to-be-created Harvard and the Legacy of Slavery Remembrance Program, through which “these descendants can recover their histories, tell their stories, and pursue empowering knowledge.”

Martha Minow (left) with panelists S. James Anaya, J.D. ’83, Pumla Gobodo-Madikizela, Densil A. Williams, and Simon P. Newman (who joined the discussion via video)

Photograph by Tony Rinaldo Photography/Courtesy of Harvard Radcliffe Institute

• Honor, engage, and support native communities. “Slavery in New England began with the enslavement of Native Americans, and Harvard leaders and staff members enslaved and sold indigenous people as well as people of African descent,” the report reads. The committee recommends financial support for research, dissemination of knowledge, recruitment of students from tribal communities, and the establishment of a conference under the Harvard University Native American Program to “advance a national dialogue on the histories and legacies of indigenous slavery and colonialism in the United States, and catalyze deep research and establish new partnerships.”

• Establish an endowed Legacy of Slavery fund to support the University’s reparative efforts. The $100 million pledged in Bacow’s message to the University community will go toward this effort.

• Ensure institutional accountability, with annual reporting and evaluation; this recommendation will be headed by the committee chaired by Minow.

On April 29, three days after the report’s release, a conference at the Radcliffe Institute gathered scholars, artists, and administrators from multiple institutions to discuss next steps. Museum curators, including Kyera Singleton, executive director of the Royall House and Slave Quarters in Medford (covered in the September-October 2020 issue, page 8L), and Kevin Young ’92, director of the National Museum of African American History and Culture, offered insights on how Harvard m ight memorialize enslaved people. Historian Jody Lynn Allen, the director of William & Mary’s slavery-reconciliation program, and Andrew M. Davenport, director of the Getting Word Oral History Project based at Thomas Jefferson’s Monticello estate, spoke of the profound and complex work involved in bringing meaningful reparative justice to sites where racial abuses had persisted for centuries.

More than one speaker noted the difficulty that lies ahead for Harvard. Anti-racism activist and historian Ibram X. Kendi argued that, “Right now, the defenders of the creed of slavery and inequality are attacking the truth, not only by spreading lies…but by attacking the credibility of the searchers and deliverers—in our case, universities and scholars and scientists.” Ruth Simmons, Ph.D. ’73, LL.D. ’02, who as president of Brown University commissioned an investigation into that institution’s ties to slavery that was the first of its kind and resulted in a 2006 landmark report, said that Harvard’s current effort may be even harder than hers was 20 years ago, “given the organized efforts to oppose truths about slavery that are now sweeping the country.”

Minow, too, echoed that concern. “Part of our work now requires vigilant attention to the reactionary responses to what we are doing here today,” she said. “I cannot help but recall the judicial reactions to the post-Civil War Reconstruction amendments in this country, undoing their meaning, undoing their intention. And we are living through, I fear, another reaction of that nature…resurfacing ideologies that some may use to justify subordination, exclusion, dehumanization. That backlash has to be part of what we understand as the legacy of slavery. And the backlash to hard-won struggles has to be what we anticipate as we do the hard work right now.”