“Alright y’all, what do we need from music tonight?” she asks. It’s 9:00 P.M. and the studio at Harvard’s ArtLab is lit only by lamps. There’s an oval of students on chairs and floor cushions in the center, and in the corner, a tapestry-covered altar with sage and a black votive candle. Clad in a denim jumpsuit and cross-legged next to a student with a keytar is professor of the practice of music and five-time Grammy-winning musician esperanza spalding. She keeps her name uncapitalized and drops the “professor” title, so to students, she’s esperanza.

Like all her weekly jams, this “is a place for us to, in a freer way, co-experience making music for each other, for our benefit—whatever that means on any given night,” 37-year-old spalding tells the students. Musicians and non-musicians are welcome. “All that we ask is that you listen, you know? That’s really the only ask, and everybody can do that.”

spalding performs at the 2009 Nobel Peace Prize concert in Oslo, Norway.

Photograph by Sandy Young/Getty Images for Nobel Peace Prize

She asks again, “So, who wants to tell us what they need from music tonight?” The students adopt a “you first” silence, punctuated only by cars whooshing past on North Harvard Street.

“Come on, throw a petal in the pond and let us ripple with you,” she says.

A flutist in spalding’s “Songwrights Apothecary Lab” songwriting course throws the first petal. “I want to feel effervescent. Sort of like this”—she plays a lick which sounds the way champagne bubbles taste. Then, a student joins on the piano, another boldly enters on the accordion, spalding creeps in on the electric bass, a few students start strumming their guitars, and everyone else dances and sings—improvising on the sound of champagne. At one point, a tap dancer puts down a mat and starts tapping. It’s like a conversation, everyone listening and responding to one another. After about 15 minutes, the conversation winds down and the flutist punctuates it with a final lick.

spalding is silent for a moment and then she smiles—wide enough to reveal the gap next to her incisor, for her nose to crinkle, and for her dimples to frame her mouth like parentheses. “That felt good,” she says. “Okay, who’s next?” And the group begins again, improvising, dancing, and “co-conjuring” together until a little after midnight.

An Invitation to the Fair

Any time spalding learned something interesting growing up, she put on a fair in its honor. Juvenile arthritis and other autoimmune disorders kept her out of elementary school for a few years, during which time she studied at home in the King neighborhood of northeast Portland, Oregon. She was a “hyperactive, self-motivated critter,” so her mother knew that, even if she left for work, spalding would finish her studies, and then some: “I would take things that were interesting to me—let’s say, like a science experiment or a game or a building project—and I would make these little fairs and invite people in the neighborhood.” She’d send out homemade invitations to “maybe eight kids and their parents,” and set up exhibit booths in her backyard. “I would invite people to come and basically just engage in the things that I found fun.”

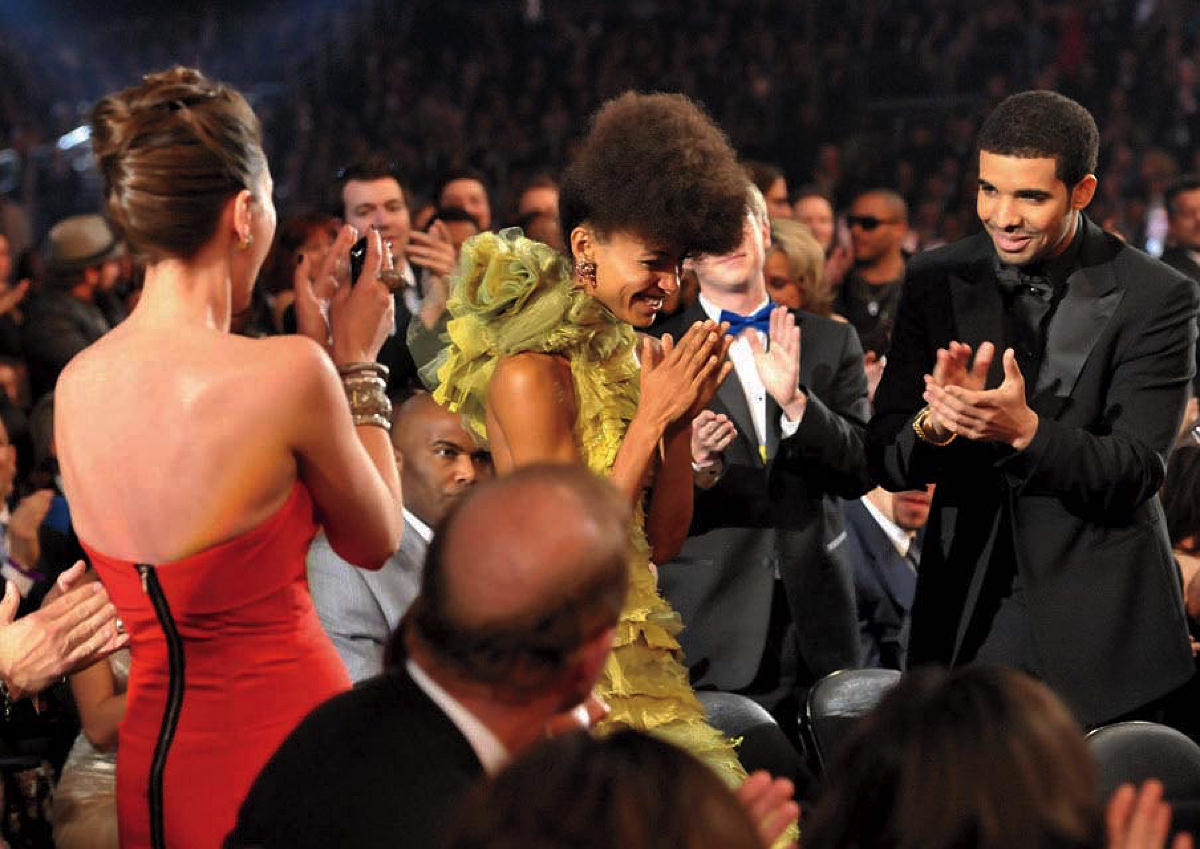

spalding wins Best New Artist at the 53rd Annual Grammy Awards, applauded by her fellow nominee, rapper Drake.

Photograph by Lester Cohen/Getty Images

For her, music was most fun. She heard Yo-Yo Ma play cello on Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood as a toddler and decided, “I want to do that. Whatever that is, I’m gonna do it.” She started violin at age four and essentially taught herself at first, because her family couldn’t afford frequent lessons. She and her older brother were raised by a single mom—a woman from tough “rural farming stock,” who worked two jobs, went back to school, figured out how to feed a family of three while in poverty, and “somehow found the time to train her kids to be critical thinkers.” The spaldings never just passively ingested television or magazines. Their mother would “try to open our eyes to a counter-commentary or counter-perspective,” she said in a Grammy interview. Once, school-age spalding used the word “prostitute,” and her mother swiftly corrected her. “No, they aren’t prostitutes. They’re prostituted women. They’re human beings.”

Welfare, food stamps, and Section 8 “literally saved our lives,” spalding has said, and local music programs helped make her into the musician she is today. She played violin in the Cultural Recreation Band (now the American Music Program), founded by local jazz musicians to get King neighborhood kids off the street and into bands. In 1989, at age five, she played with the Chamber Music Society of Oregon, a professional classical music ensemble, and became its concertmaster as a teenager. The Portland music scene was generous to her. She could go to a musician’s house, listen, jam, ask questions, and then sit in on a gig later that night. She has said, “This equation of time equals money did not exist in the education that I came from.”

At 15, she migrated from classical to jazz, and switched to upright bass. “The moment I picked up that instrument, I knew I’d never go back to violin.” She got her GED at 16 and headed to Portland State University, then transferred to Berklee College of Music, in Boston. At 20, she was appointed Berklee’s youngest instructor. People call her a prodigy, but she swears that’s not the case. “I’ve seen prodigies and I know prodigies and it’s a thing,” she said once in a podcast interview. “I have a talent in music, and I found my way early on.”

She entered the recording world in 2006 as a jazz artist. Her sophomore album Esperanza (2008) featured Brazilian jazz influences and the kind of bass solos a person would actually want to listen to. She experimented with genre-blending: Chamber Music Society (2010) occupied the sonic gray area between jazz and classical chamber music, while Radio Music Society (2012) wove jazz into airwave-friendly, sparkly melodies.

People outside the jazz world took notice. Musicians like Prince and Stevie Wonder became her admirers and collaborators, President Barack Obama selected her to play at his Nobel Prize ceremony, and in 2011, she beat tween-heartthrob Justin Bieber for Best New Artist at the Grammy Awards. The Village Voice celebrated her as the “sexiest and best thing to happen to jazz since Wynton,” and NPR dubbed her “The 21st Century’s Jazz Genius.”

But all those “signifiers”—jazz musician, genius, “sexy” female bass player—stuck to her like “burs,” spalding says. And she’s been shaking them off ever since.

The Paths Both Taken

She started down a new path in 2017, at NRG Recording Studios in North Hollywood, California. For 77 consecutive hours, spalding pulled back the curtain on her musical process as she composed, arranged, and recorded the album Exposure from start to finish. She livestreamed all of it, including her naps, on Facebook for the world to see. “I wanted to get in an environment where there was no room for any editing, filtering, or super-narratives to get imposed onto what the craft actually is,” she said in a 2019 interview. “The craft is spontaneous creativity and expression, and that’s the truth.”

Realizing that vision has meant “walking in a different direction” from jazz. She’s drawn to great music—like Shostakovich, Shabaka Hutchings, Stuff Smith, Joni Mitchell, Rimsky-Korsakov, Bad Bunny (she loves to dance to reggaeton), and Nicki Minaj—regardless of genre. She’ll always be a student of jazz, but she’s a student of many things: poetry, Reiki energy healing, the book Psychomagic by Alejandro Jodorowsky, and Nichiren Buddhism. “It’s good medicine for life.”

“Artistic growth is a little like a volcanic eruption,” she says. First, it’s disruption and upheaval, but then, the chaos cools and forms the foundation upon which beautiful new things can grow.

Artistic growth is a little like a volcanic eruption, she says. First, it’s disruption and upheaval, but then, the chaos cools and forms the foundation upon which beautiful new things can grow. “Look at Hawaii!” she laughs. This eruption has left some jazz fans in the dust. A music reporter said while interviewing her, “You had me at ‘Little Fly’ [a musical interpretation of William Blake’s “The Fly,” from her Chamber Music Society album] and you certainly held me through Exposure,” and then trailed off as if to say, “and you lost me with all the rest.”

Her new music requires listeners to relinquish any signifiers they’ve stuck to spalding. It’s not jazz, it’s not always the easiest to listen to, but as legendary jazz composer and instrumentalist Wayne Shorter has said, “it’s happening. It’s out there, but it’s interesting what she’s doing. She’s taking all kinds of chances and not giving up. If you see a fork in the road, which path should you take? Take both of them. She’s done that.”

Music as Speculative Fiction

Each song on her 2018 album 12 Little Spells is intended to activate and soothe different parts of the body—including hands and feet, but also blood, hair, the “abdominal portal,” and the “solar portal.” It opens with an ode to the thoracic spine (or as she lyrically dubs it, “12 little wells of golden ink”), and targets the hips in “Thang (hips),” where gospel organ and a slow groove support spalding’s young-Joni-Mitchell falsetto. The album is a celestial, magical, and slightly untethering experience—like opening your eyes and finding yourself in bed after a vivid dream.

12 Little Spells was her first attempt at musical “speculative fiction,” she says. It wasn’t a clinically informed piece of music therapy, but it was her way of exploring how to invite her audience into a song. As a work of science fiction might, spalding’s compositions toyed with the “what if”: “What if music could physically and spiritually support the listener?”

spalding started teaching at Harvard in the spring of 2018, the year the album came out. She taught songwriting and performance courses as a professor of practice, and started holding after-hours jam sessions, too. “I thought we really ought to have a space or a time where we can let what we’ve been studying percolate into our creative intuition and experience what it’s like to work with that in real time,” she says. During a jam, “The brain isn’t dominating. We’re really listening to each other and letting that inform what we’re creating.”

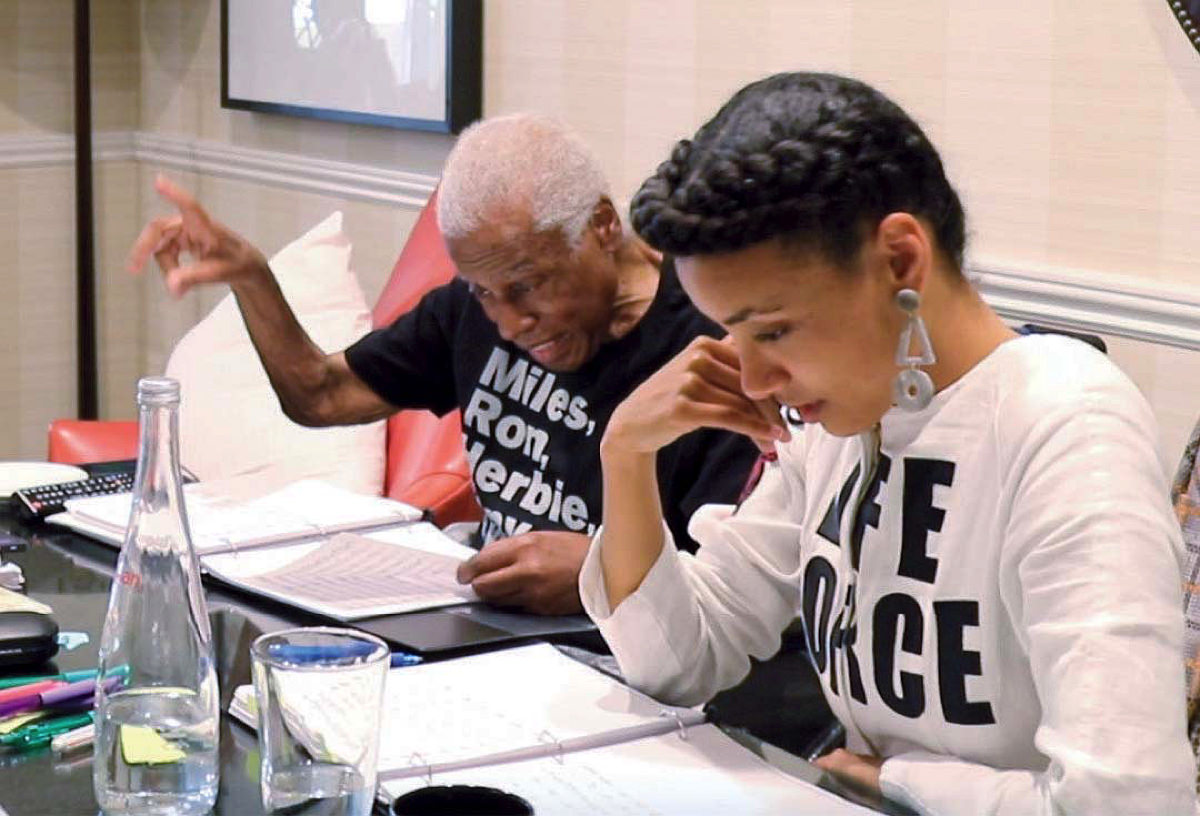

From top: spalding as Iphigenia in the opera she wrote with Shorter,(Iphigenia); spalding and Shorter in rehearsal; spalding took a leave from Harvard to finish the opera with Shorter when his health worsened.

Photographs from top: Jati Lindsay; Courtesy of Real Magic; Jeff Tang

She thinks of herself not as a professor, (“I’m not professing anything”), but as someone in “deep co-learning” with her students. She’d been collaborating with Wayne Shorter on his dream project, an opera called …(Iphigenia), for several years, when his health started deteriorating in the fall of 2019. She was in “crisis” mode and struggling to write the opera’s libretto, so she brought students into her process. She and opera expert Carolyn Abbate, Buttenwieser professor of historical musicology, co-taught a spring 2020 workshop in which students developed their own operas alongside spalding. They sat in on …(Iphigenia) production meetings, had talkbacks with the professional team, and watched an opera grow in real time. “I like to be in exploration with others,” spalding says, and Harvard students are her “co-explorers”—not her pupils.

The pandemic hit and spalding wondered again, now with more urgency: what if music could physically and emotionally support the listener? She composed and recorded her response, the Songwrights Apothecary Lab (2021), first in the Sanberg bluegrass and sagebrush of Wasco County, Oregon, then in her uncle’s living room in Portland, Oregon, and finally in Lower East Side Manhattan, at the Clemente Soto Vélez Cultural & Education Center in a theater decorated with live, sprouting mushrooms.

Singer-activist Imani Azouri and spalding perform at Radcliffe's 2019 celebration of Angela Davis

Photograph by Paul Marotta/Getty Images

She brought neuroscientists, psychologists, spiritual leaders, music therapists, and Harvard student researchers into a group she named the “Songwrights Apothecary Lab” to collaborate on the album. It was part songwriting, part guided research, says musician and clinical psychology Ph.D. student Grant Jones, whom spalding tapped as a member of the Lab. In each of the recording locations, she presented the team with the intention for each song: to give the listeners a sense of “temple-like calm,” for example, or to help them truly listen to another person. Then, the researchers combed through diverse literature—from cognitive science and psychology to poetry and mythology—to bolster the musical and lyric-writing process. It generated a unique album of dreamy soundscapes influenced by South Indian Carnatic music, featuring vocals by singer and Ph.D. student Ganavya Doraiswamy and singer and trombonist Corey King.

Always one to “demystify herself and her process,” Jones says, spalding opened portions of the Lab to the public. They held open share-backs throughout their 12-day residency in Manhattan, while they composed and recorded six of the album’s 12 songs. Members of the public could drop by, learn about the researchers’ findings, and hear the musicians tweak the songs-in-progress. They could also admire a variety of fungi. To mirror the “flowering” of the Lab’s musical arrangements, spalding commissioned a fungi artist to hang plastic bags of soil that, over the course of the Lab’s residency, sprouted into full-grown mushrooms.

Magic with a Framework

All of this sounds a little strange, and spalding knows it. She’ll often start sentences with, “This’ll sound very woo-woo, but,” and proceed to say something that’s definitely “woo-woo,” but at bottom, makes a lot of sense. She’ll say something like, “I find myself being pulled into the consciousness of 12,” and part of what she means is that, after watching loved ones go through 12-step addiction rehabilitation programs, she’s convinced the 12 steps are a powerful “healing and spiritual technology.” She hopes to incorporate its principles of honesty and surrender into her music: “I want to study, where else in arts practice have the 12 steps been introduced as a way to work through the release of dynamics or structures that don’t work anymore?”

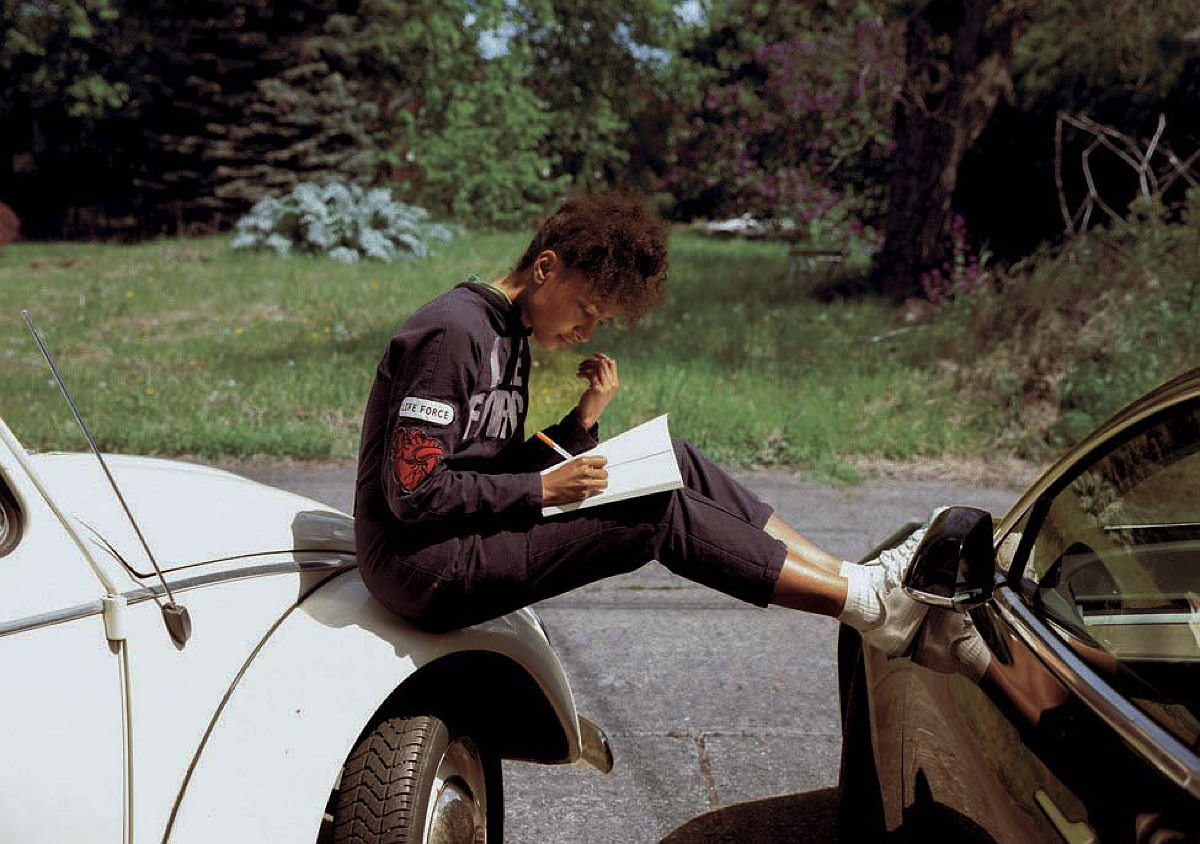

Even spalding’s outfits follow her special strain of logic. All the clothing she wears while composing or performing sports the phrase, “Life Force.” “This is my work suit,” she told a red-carpet interviewer who asked about her evening look. “There’s a lot of healing work to do, and I wanted to remind myself what team I’m working for.” Just as a superhero puts his logo on his chest, spalding puts her “ intention” on hers: “to amplify and hopefully inspire the amplification of life force in others.”

spalding wins Best Jazz Vocal Album for "12 Little Spells"at the 62nd Grammy Awards.

Photograph by Timothy Norris/Getty Images

spalding is “somehow very present with everyone she meets, but she’s also in space and under the sea at the same time,” says her friend, activist brontë velez (who does not use capitals, either). Sounds, words, smells, places, feelings—all of it sticks easily to her. It can be something silly, like a slip of the tongue. Her friend once said “hardened subliminals” instead of “hardened criminals” by mistake and it got spalding whirring: what would a “hardened subliminal” be? She followed the thread and imagined a prison in a person’s mind where all her subliminal thoughts were locked away, too “hardened” to leave. Threads like that often lead her to songs. One nudge flips the switch and “turns on a whole world,” she says. “It’s like, you didn’t know there was a switch connected to all this, and now it all starts to come to life, and you just want to tell people what you saw.”

The spalding who composed an album in 77 hours on livestream and performed songs-in-progress for the public is the same spalding who put on fairs for her neighbors. “I’m just noticing only recently that it’s not so much that this is my ‘art practice.’ This is how I like to be in community. This is how I like to learn—with others,” she says. “I like to invite other people into the looking.”

Now, she wants to transmit that sense of welcome through music: “How can more people who identify as the audience feel invited into what’s happening musically, and what’s happening in the artistic offering?” How might music become a true collaboration between the musician and listener? She thinks of her friend, pop sensation Bruno Mars. “He’s always writing for the stadium sing-along. He asks himself, what would invite a stadium of people in?” She’s not a pop musician, but “it was an ‘a-ha’ moment. Like wow, the foundation of what you’re making starts from this place of people needing to participate,” spalding says. “A lot of artists have always had that as part of their practice, so I’m not trying to invent anything new here. I’m just trying to find my version of it.”

She thinks her version will involve improvisation, between her and other musicians and maybe with her audience. “When the means of engagement are improvisation, it just opens up this whole other dimension of the experience, of connecting,” she says. “You have that simultaneity of the individual noticing how what they’re contributing is affecting the whole, but it’s creating this absolute, undeniable ‘we’ at the same time. Like wow, where else do you get to experience that?”

Jams are her laboratory. Whether it’s at Harvard or the other jam sessions she curates in the Bronx and Portland, she asks herself, “What is the general structure that gives people a sense that they can relax?...What are the terms and structure we need so that we can really improvise and be in agenda-free exploration together?” And “Who felt comfortable to participate and why?” She changes the prompts she gives the musicians and how often she interjects from jam to jam. Each time, she learns a little more about how to make music people can engage with. “She’s an empiricist,” Jones says. Her creative process is “magic, definitely—but it’s magic with a framework.”

Ir Manejando/irma nejando

In the fall of 2020, on her thirty-sixth birthday, spalding announced her new name: “irma nejando.” While “esperanza spalding” continues to be her stage name, she’s “irma” in her daily life. The name is a play on the Spanish “ir manejando” (to drive toward) and it’s also an intention: “If esperanza [Spanish for “hope”] is what I am, I invite irma to be a lived expression of hope in action.” The name change ushered in a new chapter and carved a distinction between “esperanza spalding,” the name covered with signifiers, and the real person underneath.

A lot of burs still stick to “esperanza spalding.” Some listeners continue to think of her as a “demure lady” and the closest thing jazz has to a sex symbol. People in power sometimes “talk to me like I’m a little girl,” she says. “They patronize me and think that I will entertain it. And I just don’t.” She adds, “I try to treat people with equanimity just based on the fact that we’re humans here on earth together. Like, that’s already interesting. We already have a right to be in conversation with each other, you know? So, when someone behaves out of their seat of power towards me, I just don’t entertain it.”

spalding regularly has outdoor "listening sessions" to find melodies in the sounds of nature.

Photograph by Holly Andres

But spalding says, “I’m trying to have more grace when I feel that there’s a dynamic like that at play, because we’ve all been socialized one way or another and it’s probably coming from a place of habit. I long to be able to connect with the human, the person, and we’re more than just our behavior.”

Despite her best efforts, she’s still labeled as a jazz artist. 12 Little Spells and Songwrights Apothecary Lab were both awarded the Grammy for Best Jazz Vocal Album and were listed on the Billboard jazz charts. It’s doesn’t bother spalding, though, because she’s her mother’s daughter. When she told her mom she was nominated for a Grammy, her mother congratulated her and then quickly moved into a discussion of a newspaper article she thought spalding might like to read.

Her mom “is not very concerned with how the dominant culture perceives your successes, because she’s never really operated along that value-scale….Her worldview really colors the way I do things,” spalding has said. Her mother is interested, above all, in “how we treat each other.” And for spalding, treating others well means inviting them in.