WHEN WILLIAM TAMPLIN, Ph.D. ’20, first came across Cry in a Long Night, the 1955 Arabic novel for which his English translation was published earlier this year, he was searching for something else entirely. As a graduate student in comparative literature, pursuing what would eventually become his dissertation topic, Tamplin had been looking online for scholarly papers about apocalypticism in Arabic fiction. During college, he’d spent time in the Middle East, and he was struck by how often people there spoke about the end of the world. “It was ubiquitous,” he says. “You could ask anyone, ‘Hey, do you think the end times are near?’ and even a normal-looking dude on the street would say, ‘Yeah, people say they are,’ and then they’d give evidence for it based on the Koran or on the geopolitical situation.” This was in the early 2010s, as the Arab Spring’s pro-democracy uprisings gave way to Syria’s bloody civil war and ISIS, preaching a doomsday vision, began gaining territory in Iraq and Syria. “Apocalypse was on probably every religious Arab Muslim’s mind,” Tamplin says. “Once I saw that, I thought, ‘Well, what about Arabic literature?’”

Tamplin’s interest in Arabic had begun early. “I was 11 years old when 9/11 happened,” he says. “And the years after that were full of news from Afghanistan and Iraq.” Later, in high school in Louisville, Kentucky, he saw a classmate in AP statistics teaching himself Arabic using a primer. “I thought that was pretty cool,” Tamplin says. “So I bought the same primer and taught myself the alphabet.” His senior year, he took a course in Arabic at the University of Louisville, and when he arrived at Georgetown for college, dove even deeper. He read Naguib Mahfouz’s The Dreams, a book whose haunting, poetic stories “hit me over the head.” He studied abroad in Egypt and then Jordan. “I remember all the dust in the air,” he says of those first experiences in the Middle East. “And then I remember getting to Alexandria and having a really strong sea breeze whip you everywhere. The mangos were fruitier and the coffee was stronger.” Human interactions were more intense, too. “The people who were hostile were really hostile—they’d call you names and throw stuff at you—but the people who were kind were extremely kind. They’d open their homes to you.”

After graduating in 2012, he took a job with an English-language school in Egypt, but stayed for only a couple of months before political protests and instability forced him home. The following year, he returned to Jordan on a Fulbright scholarship studying Bedouin poetry and deliberated about what to do next. At his brother’s urging (“You seem to love this”), he applied to doctoral programs; Harvard said yes, and he came to Cambridge. “I think I told myself that I was either going to go to grad school in literature or join the Marine Corps,” Tamplin says. His grandfather had been a Marine, and the thought of joining had been with him since he was 12.

Tamplin (middle) being air-inserted into a landing zone for a field exercise with fellow Marines.

Photograph courtesy of William Tamplin

In the end, the Marine Corps won out. Tamplin entered officer candidate school this January, and by the time his translation of Cry in a Long Night was released in May, he had accepted an officer’s commission. “Toward the end of grad school, it became pretty clear that I was either not going to get a job in academia, or it was going to be a lot of years of postdocs, fellowships, and visiting assistant professor jobs here and there before I landed a tenure-track job, if at all,” he says. The Marines, he decided, offered a more rewarding path.

DURING THAT online search in his early years of graduate school, Tamplin didn’t find much scholarly analysis of Arab literary apocalypticism—that was ground he’d mostly have to break himself. But in one journal article, he did find a brief mention of Cry in a Long Night, by Jabra Ibrahim Jabra, a renowned Palestinian poet, writer, translator, and painter. In the book’s introduction, Tamplin recalls that an Israeli critic had suggested the novel, set sometime in the mid-twentieth century, offered an apocalyptic “prophesy of the ‘doom’ about to befall the Palestinian people” at the 1948 founding of Israel. So, Tamplin checked out the book from Harvard’s library to read over a winter break.

Jabra Ibrahim Jabra, in the photograph that accompanied his application for a Rockefeller Foundation fellowship at Harvard in 1952

Photograph courtesy of the Rockefeller Archives

He couldn’t put it down. The language was beautiful, lyrical. It was almost music. And the book was strikingly modern, unfolding in interior monologues, flashbacks, and stream of consciousness, all told by an intimate first-person narrator. This was nothing like the other Arabic novels he’d read from that period, which were heavily allegorical and naturalistic. Jabra had spent the first few years of World War II at the University of Cambridge, immersing himself in British literature; he loved the English Romantic poets—Shelley, Keats, Byron; he’d read T.S. Eliot’s “The Waste Land.” He was an admirer of James Joyce, Virginia Woolf, D.H. Lawrence, and William Faulkner; soon after Cry in a Long Night came out, he published a translation of Faulkner’s The Sound and the Fury. Those influences show up unmistakably in Jabra’s work, Tamplin says: “Jabra focuses on the self, the individual. A lot of Arabic literature before this had been focused on the collective, the nation. It’s not like this novel doesn’t have the nation in mind, but it’s extremely personal. It goes into the intricacies of his mind and his life experiences. The main character is a complex person. This is not a propaganda piece.”

The book follows 28-year-old Amin Samaa, an Arab Christian, who is a novelist and journalist. He spends his nights helping an aristocratic heiress write a 300-year history of her Ottoman family and, with it, the city where they both live (unnamed and allegorical, but resembling Jerusalem). This is a project that involves poring over family letters, papers, and diaries in the basement of her family’s palace. The narrative takes place during a single night, as Samaa walks from his home on one side of the city to the heiress’s on the other. Along the way, he muses about the wife who has left him, his childhood in a nearby village, his relationship with his dead father, the slum to which his family had to flee when he was a boy. In the final chapters, those threads weave together in a fiery, decisive cataclysm.

AS TAMPLIN writes in the introduction, Cry in a Long Night was a strange book to translate into English. In part, that’s because it was apparently originally written in English. Jabra claimed to have first composed the novel in Jerusalem during the summer of 1946, with the English title Passage in the Silent Night. In those days, Tamplin writes, Jerusalem “was an apocalyptic city fraught with random explosions and terrorist violence” as the British administration of Palestine was coming to an end and the Arab and Israeli communities there prepared for war. In January 1948, amid the fighting, Jabra fled to Baghdad, where he would live out the rest of his life. In the early 1950s, while studying literary criticism at Harvard on a Rockefeller Foundation Humanities Fellowship, he translated his novel into Arabic and published it in 1955.

That original English manuscript seems to have been lost. Most likely it disappeared in the explosion that destroyed Jabra’s family home in Baghdad in 2010, when a suicide bomber targeted the Egyptian embassy nearby. Dozens of people were killed and hundreds injured. Many of the buildings along the street were damaged. By then, Jabra had been gone for years—he died in 1994 at age 75—but the explosion took his library, containing countless personal papers, letters, diaries, books, and paintings.

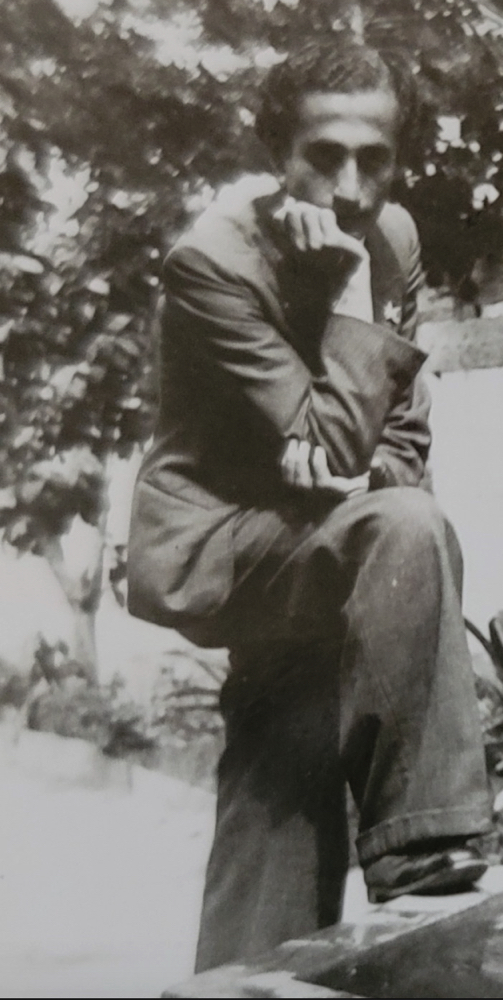

Jabra in the 1930s, before he left for England

Photograph courtesy of George Kiraz

A huge loss, Tamplin says, not least because, for all his renown, Jabra remains largely a mystery. He was beloved and brilliant, the author of two autobiographies, six autobiographical novels, and dozens of personal essays, but he kept many secrets: throughout his life, he maintained the fiction that he was born in Palestine; in fact, Tamplin discovered through years of obsessive research, he was born in a city called Adana, in modern Turkey, to a Syriac Christian family that had survived a genocide by the Ottoman regime. (During the 1910s, roughly half the world’s population of Assyrians at the time—250,000 people—perished in the Sayfo genocide.) In the early 1920s, when Jabra was only a few years old, his family escaped to Bethlehem. “All of his earliest memories are from there—it’s absolutely fair to call him a Palestinian,” Tamplin says. “He was also educated in Palestinian institutions set up by the British, which were meant to inculcate a sense of Palestinian identity.” But he allowed people—friends, readers—to believe he was born in a place where he wasn’t. “Why Jabra never mentioned his traumatic family history is a mystery,” Tamplin writes in the book’s introduction. “Perhaps it was too much for him to countenance. Perhaps it distracted from both his profound sense of Palestinian identity and his lifelong project to modernize the Arab world culturally and artistically.” Tamplin doesn’t condemn the deception; he finds it interesting, perplexing—a profound burden that Jabra carried. “And so I tried to get at why,” he says.

In 2021, he published an article in Jerusalem Quarterly, “The Other Wells: Family History and the Self-Creation of Jabra Ibrahim Jabra,” which dug into government documents, foundation records, and other archival evidence to contextualize a picture of the author’s life and family history. Tamplin also interviewed people who had known Jabra, and found that even decades after his death, the subject of his birthplace was delicate. “There are some social dynamics in the Arab world that are so sensitive that you can hardly talk about them,” he says. He often wonders what might have been revealed in Jabra’s destroyed library. “Sifting through his archives would have been eye-opening,” he says. “Instead, literary biographers have to rely on speculation and hearsay.” Even Jabra’s claim about Cry in a Long Night being written first in English is unverified, Tamplin points out. “We just have to take his word for it.”

Jabra, Tamplin says, was a pioneering modernist and “in my opinion, perhaps the most sensitive and personal Arab writer of the twentieth century. I wish we had more definitive knowledge about this man.”

EVEN AS Tamplin’s career heads off in a new direction, his engagement with Jabra continues. Recently, he translated one of the author’s later novels, The Other Rooms (which he plans to publish just as soon as he finds time to pull together a book proposal in between field exercises with his platoon). Like Cry in a Long Night, The Other Rooms takes place in an unnamed Arab city over the course of a single night. But published much later, in 1986, it is “a study in shifting identity” with a plot reminiscent of Franz Kafka’s The Castle, Tamplin writes in his Jerusalem Quarterly article. The protagonist “who has forgotten who he is, is led through different rooms in a government building and interrogated. He does not know where he is being led and why. At one point he looks in a mirror and does not recognize himself.” Tamplin believes the book ought to be understood in the context of “Jabra’s life of alienation, exile, and name-changing”—a life surely colored by Saddam Hussein’s Iraq, the unending crisis of Palestine, and the genocide his family had survived.

What emerges from all those strands of experience, and from Jabra’s own literary imagination, Tamplin says, are books that “offer up what the best of literature from anywhere in the world has to offer”: depth, beauty, revelation—“everything.”