On a Sunday afternoon, the airy lobby of the Mattatuck Museum in downtown Waterbury is alive with sound. The Connecticut Accordion Association Orchestra, back by popular demand, plunges into “Moonlight Serenade” as listeners nod along or enjoy a late lunch from the Art of Yum Café. Even the security guard at the reception desk sways to the beat. Paintings loom large on lobby walls. In Our Housekeepers (2008), by Duvian Montoya, a brown-skinned woman bows over bedsheets. Tajh Rust’s The Freemen (2017) shows an African American father in track suit and gold sneakers at home, his hand on his small son’s head like a protective cap.

The whole scene epitomizes a confluence of artistic styles and people, of activities amid a welcoming ambience, that reflect the transformation of this cultural institution during the last decade. Reopened in 2021 following a $9-million expansion and renovation, the place is, for many, an oasis of artistic spirt in the heart of a downtrodden, postindustrial New England city, which never fully rebounded from its “Brass City” heyday as the leading manufacturing center for the nation’s brassware.

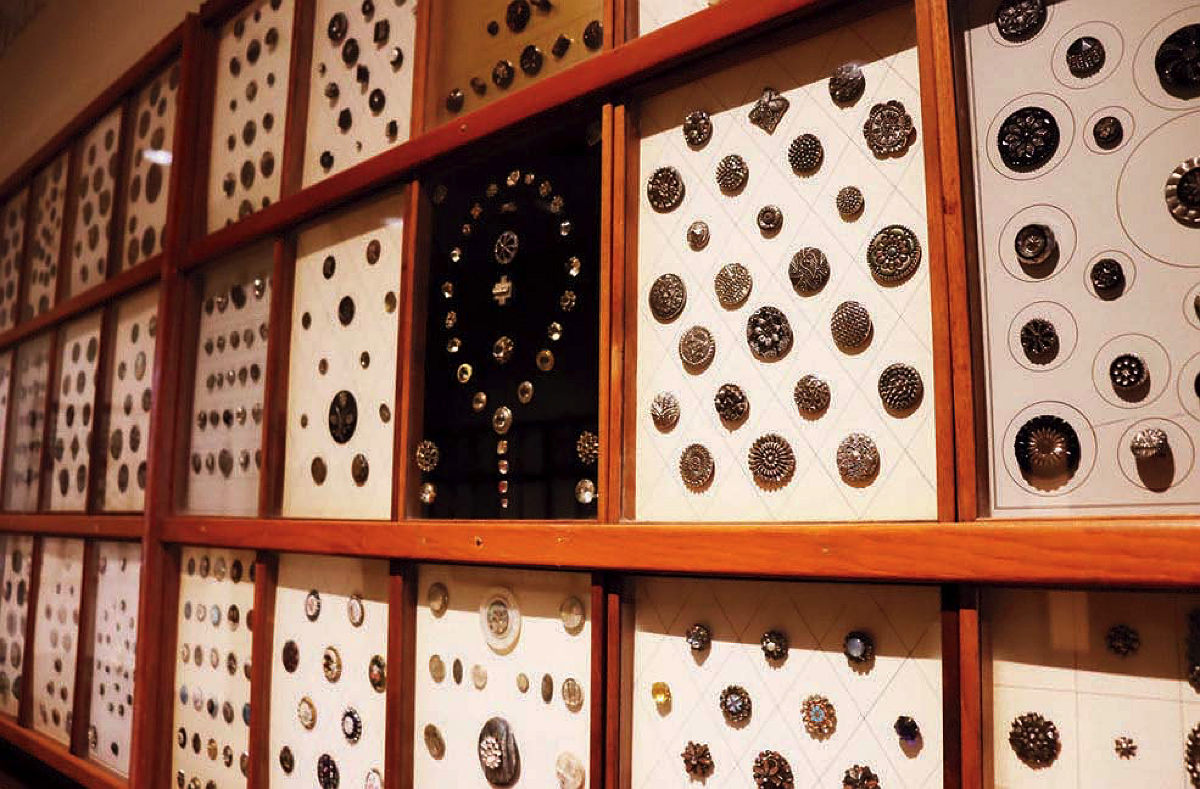

A glimpse of the museum’s 3,000-plus button collection

Photograph courtesy of the Mattatuck Museum

“When I first got here in 2012, this was a sleepy little museum,” says executive director Bob Burns, “more of a private social club.” Demands for change sprang from every corner. Upon seeing the grand tally of daily visitors—16—Burns thought, “Oh, no, that’s not going to work.” Morover, the building itself posed a problem. A former Masonic temple, and home since 1987 to the Mattatuck Historical Society (founded in 1877), he says the brick façade with blackened windows screamed “Stay out!” And, like many historical societies, any exhibits were laboriously mounted, then stayed up for years. And years. “There was no reason for people to keep coming back here,” he says, but the board of directors loved (and still love) the city and had a vision “that something good could come out of this that would benefit the rest of the community.”

That first good thing was Burns. Having worked in arts development and fundraising, most recently at Olana, the historic estate of Hudson River artist Frederick Church, he is also married to Gary Schiro, the force behind a 16-year effort to resurrect the historic opera house in the upstate arts mecca of Hudson, N.Y., where they lived. Thus, even faced with challenges, Burns saw big opportunities. “I really wanted to breathe life into this Waterbury place that has so much rich history and an amazing collection.”

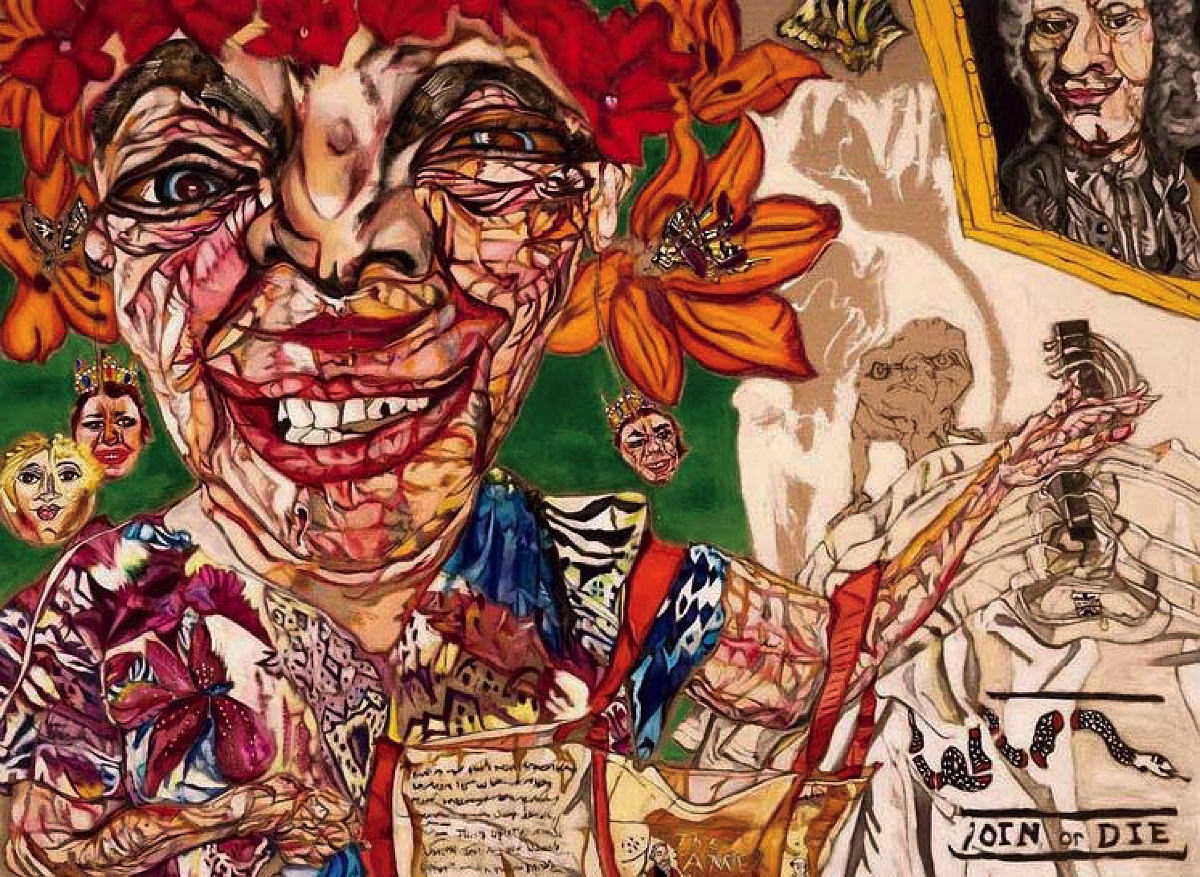

Gift Shop (2021), by Schandra Singh

Photograph courtesy of the Mattatuck Museum

The renovation added 14,000 square feet of new gallery space and classrooms, along with the large lobby entrance, restaurant, and popular roof deck that overlooks the city green (also recently revamped). The café is locally owned and operated by a local family—chef Michone Denaé Arrington was named “Best New Chef” by Connecticut Magazine—and draws fans. Perhaps most importantly, the design (by Ann Beha Architects, now Annum Architects, in Boston) broke open the building’s imposing brick façade, creating glass windows and a bank of front doors that beckons visitors. More than a dozen rotating exhibitions a year keep the galleries fresh, as do a steady flow of lectures and art classes, children’s programs, yoga and tai chi sessions, performances, MATT@NIGHT events for the 21-plus crowd, and other art- and local-history-related programming.

Exhibitions run the gamut. “We pull art from our shelves, and we do contemporary artists, but we also do some sponsored and traveling shows,” says Burns. “We try to be thoughtful and creative.” Mattatuck is an art and history museum, but Burns has also redefined “representing Connecticut” to reflect the state and city of today “and what this community is,” he says, “which is extremely diverse.”

Spick&Span, by Robyn Tsinnajinnie

Photograph courtesy of the Mattatuck Museum

Some 500 new works, acquired and donated since Burns arrived, have increased art by women and artists of color, for example. On display now are: Janet Maya’s Georgia I (2021), Harriet Whitney Frishmuth’s sculpture Crest of the Wave (1925), and Anna Richards Brewster’s Ardsley Road Bridge (c. 1930). Otherwise, the museum’s core collection “spans the eighteenth century to the present and includes a range of objects as diverse as industrial machines to mobiles by Alexander Calder,” says chief curator Cecelia “Keffie” Feldman. Many of Calder’s sculptures of the 1960s and 1970s were fabricated in Waterbury, at Segre’s Ironworks, on Reidville Drive.

The newly curated first-floor gallery presents Waterbury’s history by subject area. It delves into the brass industry’s local origins—in 1802, Abel Porter & Co was formed to manufacture buttons and sewing hardware, and then grew into the versatile Scovill Manufacturing complex, employing 12,000 people at its peak—to its demise in the 1970s. (Check out the Mattatuck’s top-floor display of more than 3,000 buttons, including those with floral designs crafted from human hair and the engraved discs that once adorned a coat worn by General George Washington.) Permanent exhibits also highlight Waterbury’s role in developing photography, lighting devices, clocks and watches, war-time products, and industrial machinery.

This season, rotating exhibit space offers new paintings and classic photography. Schandra Singh: Fractured Facades, through November 27, explores outsized, patchworked portraits by the Rhode Island School of Design-trained artist. Her up-close faces or bodies float in a sea of bright landscapes, even as the works evoke a sense of distortion or disturbances. Also on view, through December, are 60 black-and-white images in Walker Evans: American Photography. They capture the mood of the Great Depression, revealing people within social contexts, and the era’s architectural landscape. In a third gallery, a group show—Work It! Women Artists on Women’s Labor—reflects the multifaceted roles women play throughout their lives (through December 31).

The museum strives for that “sweet spot,” says Burns, with affordable admissions pricing and a range of events and exhibits. “Our community is largely disadvantaged, and our audience is super-advantaged, so where do we find a middle ground?” he asks. “By trying to connect with our actual neighbors and also trying to engage them with our core constituency, and we do that with creative exhibitions, events, and programming—that change constantly.”