Put a fleck of paint under a microscope, and it tells a story. “Portrait of a Woman,” an Egyptian funerary portrait from the second century C.E., began with a piece of wood from a sycamore fig tree (Ficus sycomorus). The unknown artist (or artists) coated the wood with white calcium sulfate and created opaque paint by binding pigments—bone black, madder lake, red and yellow ochres, alunite, bassanite, anhydrite—to animal glue. Then, with unblended strokes of color, he gave life to her delicate wrinkles, large eyes, and graying hair.

The woman’s likeness is one of several funerary portraits on display through December at the Harvard Art Museums’ exhibition “Facing Forward,” which highlights the portraits’ context in ancient Egypt—and scientific analysis conducted at the museums’ Straus Center for Conservation and Technical Study. In the first three centuries C.E., Egypt was a province of the Roman Empire, and Roman art styles found their way into Egyptian burial practices. Artists produced individualized portraits of the deceased to place over their faces and secure with burial linens.

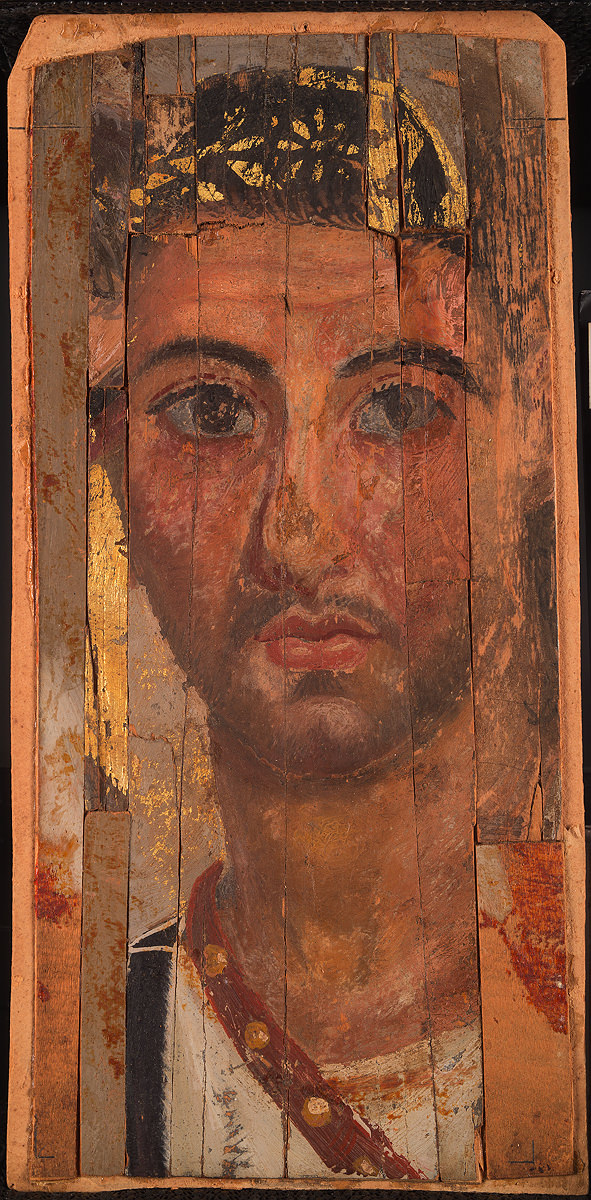

A composite portrait of a man, reassembled long ago with pieces not from the original workImage courtesy of the Harvard Art Museums/©President and Fellows of Harvard College

Original painting under normal light on left and on the right under infrared reflectography. The portrait is made in the "encaustic" style, in which pigments were bound to beeswax. The style is characterized by life-like facial features and a depth of color similar to that of an oil painting.Images courtesy of the Harvard Art Museums/©President and Fellows of Harvard College

In the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, antiquities dealers separated hundreds of these funerary portraits from mummified remains and sold them to collectors—sometimes with the burial linen of the deceased still stuck to the back. Hanfmann curator of ancient art Susanne Ebbinghaus says the exhibition underscores curatorial dilemmas: “How do we do these individuals justice? How do we help commemorate their burials that museum practice and collecting practice essentially destroyed?”

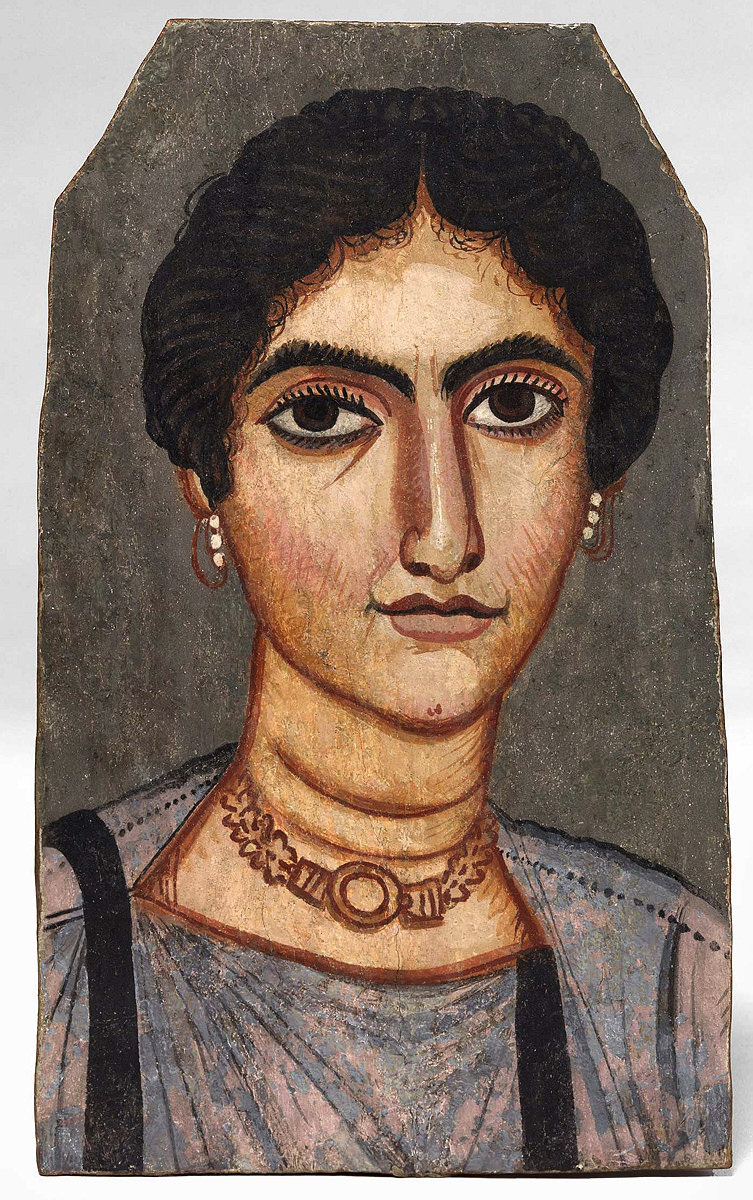

Portrait of another woman in the "tempera" style, characterized by animal glue binding, layered paint, and dramatized facial features.Image courtesy of the Harvard Art Museums/©President and Fellows of Harvard College

To honor the woman in the portrait, modern scholars tried to learn as much as they could about her likeness. According to customs and collections stickers, Austrian businessman Theodor Graf acquired the painting in the late 1800s, sold it to a Viennese art dealer, who then sold it to the Rockefeller family, who donated it to Harvard in 1939. An X-radiograph of the portrait displayed in the exhibit reveals that the artist used rare red lead paint on her lips—perhaps because Egyptians emphasized the lips as the sacred site of breath and speech—and at some point, someone added new wood to make the oval-shaped panel into a more marketable rectangle for art collectors. In an ultraviolet-induced fluorescence image, modern white zinc pigments glow bright green, evidence of a previous restoration.

Original under normal light on the left and x-radiography on the right, revealing the wooden grid or "cradle" restorers long ago attached to the back to prevent the wood from curvingImages courtesy of the Harvard Art Museums/©President and Fellows of Harvard College

“This exhibit was born as an opportunity to show how we know what we know about these works of art, and how that can deepen our understanding of what they are and what they aren’t,” says conservator of paintings and head of paintings lab Kate Smith. We may never know who the woman in the portrait was, but now at least we know how her likeness was made, and the path it’s taken since.