Should the United States pay reparations for slavery? As controversial as that question is, the federal government in fact has a long history of providing compensation to people who have suffered harms of all kinds through no fault of their own: from people exposed to pesticides or nuclear radiation, to indigenous peoples, to farmers who’ve lost crops, to people harmed by vaccines or the closure of a factory or military base. These payments amount to “billions of dollars every year to millions of Americans,” says Moynihan senior lecturer in public policy Linda Bilmes, “and they’re fairly routine.”

Bilmes, former assistant secretary of the U.S. Department of Commerce, and Hauser professor of the practice of nonprofit organizations Cornell Brooks, of the Harvard Kennedy School (HKS), have been documenting the scope, administration, and funding mechanisms of what they term “reparatory compensation.” They’ve found that no-fault programs to make people whole—whether they are for Christmas tree farmers, ginseng growers, or one of a hundred different kinds of fisherman—number in the thousands. Reparations in the strict sense have also been paid in cases of official injustice—for instance, to Japanese Americans held in internment camps during World War II. Brooks, who once worked as a civil rights attorney in the Department of Justice, recalls that in his building there were government attorneys “assisting the effort to provide reparations for victims of the Holocaust.” But there was never any discussion of reparations for slavery.

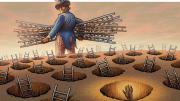

Aiding the pair in their effort to catalog such government compensation programs were the leaders of the Black Students Associations at both HKS and the Law School, and two other students. As Bilmes turned up programs for sardine fisherman, clam fisherman, coal miners, descendants of veterans, and countless others, she didn’t initially understand why the students “were not as delighted by all these things we were uncovering. Until I realized that this was actually extremely painful for them, to see that there were programs for everyone but them. Essentially, the government had figured out all kinds of reparatory mechanisms, programmatically and financially, for everyone else.”

In this context, the lack of reparations for slavery seems a striking omission. When the subject arises, says Brooks, former president and CEO of the NAACP, three fundamental objections are typically raised: that slavery took place too long ago to be able to trace its harms into the present, that paying such reparations would be too expensive, and that it would be administratively impossible to execute.

Belying the first objection—that the victims are no longer living—Bilmes and Brooks point to an analogous (and related) event that is instructive to consider: the connected, intergenerational harms caused by the implementation of the G.I. Bill from 1944 through 1955. The bill provided veterans with guaranteed home loans, money for college or trade-school training, and unemployment compensation. The 1.8 million eligible black American veterans were not explicitly excluded by the federal legislation, but at the insistence of congressmen from Jim Crow states, implementation was left to the states, and widespread discrimination, particularly in the South, where 79 percent of black veterans lived, prevented most from taking advantage of the program. Even in New York and New Jersey, Bilmes and Brooks report, the 67,000 mortgages guaranteed by the legislation included fewer than 100 granted to non-whites because of discrimination by lenders. In Mississippi, just two such loans were made to black veterans. Nearly eight million veterans in total took advantage of the bill’s education benefits; most black veterans who did so were sent to one of the tiny and underfunded historically black colleges and universities (HBCUs). “That meant that there were fewer black doctors, architects, and engineers,” says Brooks, because among the HBCUs “there were virtually no schools of engineering, no schools of medicine.” And blacks were likewise excluded from trade schools and prevented from learning skills that would have enabled them to become plumbers or electricians. “The point being,” Brooks continues, “that the G.I. Bill operated in an ecosystem of racism, linked all the way back to slavery.”

And because the education and homeownership opportunities provided by the bill underlay the creation of intergenerational wealth, the harms to black veterans who did not receive benefits “accumulate and they compound,” he says, harming children, grandchildren, great-grandchildren, and so on. “The effects of redlining, predatory lending, depreciating house prices, and impaired economic viability of communities all contribute in tangible, empirically demonstrable ways to the racial wealth gap. Any fair-housing lawyer will tell you those are some of the easiest ones to calculate.” Recent legislation, the Sargent Isaac Woodard and Sargent Joseph Maddox G.I. Bill Repair Act, would allow surviving spouses and some direct descendants of black World War II veterans denied benefits under the original G.I Bill to access home loans and educational assistance through existing programs.

The government uses a range of financial tools to pay for reparatory compensations: excise taxes, special assessments, and trust funds….

Bilmes says that the research shows that “The government really uses a range of financial techniques and tools and mechanisms to pay for these reparatory compensations: a combination of excise taxes, special assessments, trust funds, and subsidized insurance.” In the realm of insurance, the familiar example is that the “FDIC insures bank deposits to $250,000 per account.” The government also “subsidizes no-fault flood insurance and agricultural insurance of many different kinds.”

But beyond these insurance mechanisms, she continues, there are dozens of different kinds of funding mechanisms, and there are precedents for intergenerational compensation. For instance, “Hundreds of thousands of people and their children and grandchildren who were exposed to nuclear radiation in 12 western states during Cold War weapons testing between 1945 and 1960 are covered by a cluster of different programs that recognize different groups and categories of harm.” Those programs began in the late 1990s, after 50 years of citizen advocacy, and have paid out $25 billion. President Clinton’s executive order establishing the programs conveys their spirit: “While the nation can never fully repay these workers or their families, they deserve recognition and compensation for their sacrifices.”

Although Bilmes’s and Brooks’s research project focused only on federal compensation, there are state-level programs, too. And other entities, including a number of universities, have been reckoning with their connections to slavery. Georgetown, for example, has allocated $400,000 a year to reparations that will benefit the descendants of slaves sold by the school in 1838 to secure its finances. The Princeton Theological Seminary has set aside $27.6 million to fund a million-dollar annual reparations effort. And Harvard’s report on its connections to slavery allocates $100 million for future actions, though it doesn’t embrace reparations (see “Harvard’s Ties to Slavery,” July-August, page 22).

The data that Bilmes and Brooks have gathered demonstrate that existing reparatory compensation programs are manageable and commonplace. They hope that their research will influence the debate over reparations for slavery. “In our paper,” says Brooks, “we essentially say, If reparatory compensation is routine and normal, why would we consider reparations to be aberrational and exceptional? I hope this project popularizes the notion that we can afford it,” he continues, “we can do this, and that the harm was not too long ago. America is skilled in reparations.”